Each aircraft has a specific pitch attitude and airspeed that corresponds to the most efficient climb rate for a specified weight. The POH/AFM contains the speeds that produce the desired climb. These numbers are based on maximum gross weight. Pilots must be familiar with how the speeds vary with weight so they can compensate during flight.

Entry

Constant Airspeed Climb From Cruise Airspeed

To enter a constant airspeed climb from cruise airspeed, slowly and smoothly apply aft elevator pressure in order to raise the yellow chevron (aircraft symbol) until the tip points to the desired degree of pitch. [Figure 1] Hold the aft control pressure and smoothly increase the power to the climb power setting. This increase in power may be initiated either prior to initiating the pitch change or after having established the desired pitch setting. Consult the POH/AFM for specific climb power settings if anything other than a full power climb is desired. Pitch attitudes vary depending on the type of aircraft being flown. As airspeed decreases, control forces need to be increased in order to compensate for the additional elevator deflection required to maintain attitude. Utilize trim to eliminate any control pressures. By effectively using trim, the pilot is better able to maintain the desired pitch without constant attention. The pilot is thus able to devote more time to maintaining an effective scan of all instrumentation.

The VSI should be utilized to monitor the performance of the aircraft. With a smooth pitch transition, the VSI tape should begin to show an immediate trend upward and stabilize on a rate of climb equivalent to the pitch and power setting being utilized. Depending on current weight and atmospheric conditions, this rate will be different. This requires the pilot to be knowledgeable of how weight and atmospheric conditions affect aircraft performance.

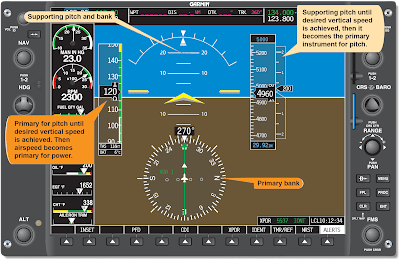

Once the aircraft is stabilized at a constant airspeed and pitch attitude, the primary flight instrument for pitch will be the ASI and the primary bank instrument will be the heading indicator. The primary power instrument will be the tachometer or the manifold pressure gauge depending on the aircraft type. If the pitch attitude is correct, the airspeed should slowly decrease to the desired speed. If there is any variation in airspeed, make small pitch changes until the aircraft is stabilized at the desired speed. Any change in airspeed requires a trim adjustment.

Constant Airspeed Climb from Established Airspeed

In order to enter a constant airspeed climb, first complete the airspeed reduction from cruise airspeed to climb airspeed. Maintain straight-and-level flight as the airspeed is reduced. The entry to the climb is similar to the entry from cruise airspeed with the exception that the power must be increased when the pitch attitude is raised. [Figure 2] Power added after the pitch change shows a decrease in airspeed due to the increased drag encountered. Power added prior to a pitch change causes the airspeed to increase due to the excess thrust.

When making changes to compensate for deviations in performance, pitch, and power, pilot inputs need to be coordinated to maintain a stable flight attitude. For instance, if the vertical speed is lower than desired but the airspeed is correct, an increase in pitch momentarily increases the vertical speed. However, the increased drag quickly starts to degrade the airspeed if no increase in power is made. A change to any one variable mandates a coordinated change in the other.

Conversely, if the airspeed is low and the pitch is high, a reduction in the pitch attitude alone may solve the problem. Lower the nose of the aircraft very slightly to see if a power reduction is necessary. Being familiar with the pitch and power settings for the aircraft aids in achieving precise attitude instrument flying.

Leveling Off

Leveling off from a climb requires a reduction in the pitch prior to reaching the desired altitude. If no change in pitch is made until reaching the desired altitude, the momentum of the aircraft causes the aircraft to continue past the desired altitude throughout the transition to a level pitch attitude. The amount of lead to be applied depends on the vertical speed rate. A higher vertical speed requires a larger lead for level off. A good rule of thumb to utilize is to lead the level off by 10 percent of the vertical speed rate (1,000 fpm ÷ 10 = 100 feet lead).

To level off at the desired altitude, refer to the attitude display and apply smooth forward elevator pressure toward the desired level pitch attitude while monitoring the VSI and altimeter tapes. The rates should start to slow and airspeed should begin to increase. Maintain the climb power setting until the airspeed approaches the desired cruise airspeed. Continue to monitor the altimeter to maintain the desired altitude as the airspeed increases. Prior to reaching the cruise airspeed, the power must be reduced to avoid overshooting the desired speed. The amount of lead time that is required depends on the speed at which the aircraft accelerates. Utilization of the airspeed trend indicator can assist by showing how quickly the aircraft will arrive at the desired speed.

To level off at climbing airspeed, lower the nose to the appropriate pitch attitude for level flight with a simultaneous reduction in power to a setting that maintains the desired speed. With a coordinated reduction in pitch and power, there should be no change in the airspeed.

Descents

Descending flight can be accomplished at various airspeeds and pitch attitudes by reducing power, lowering the nose to a pitch attitude lower than the level flight attitude, or adding drag. Once any of these changes have been made, the airspeed eventually stabilizes During this transitional phase, the only instrument that displays an accurate indication of pitch is the attitude indicator. Without the use of the attitude indicator (such as in partial panel flight), the ASI tape, the VSI tape, and the altimeter tape shows changing values until the aircraft stabilizes at a constant airspeed and constant rate of descent. The altimeter tape continues to show a descent. Hold pitch constant and allow the aircraft to stabilize. During any change in attitude or airspeed, continuous application of trim is required to eliminate any control pressures that need to be applied to the control yoke. An increase in the scan rate during the transition is important since changes are being made to the aircraft flightpath and speed. [Figure 4]

|

| Figure 4. The top image illustrates a reduction of power and descending at 500 fpm to an attitude of 5,000 feet. The bottom image illustrates an increase in power and the initiation of levelling off |

Entry

Descents can be accomplished with a constant rate, constant airspeed, or a combination. The following method can accomplish any of these with or without an attitude indicator. Reduce the power to allow the aircraft to decelerate to the desired airspeed while maintaining straight-and-level flight. As the aircraft approaches the desired airspeed, reduce the power to a predetermined value. The airspeed continues to decrease below the desired airspeed unless a simultaneous reduction in pitch is performed. The primary instrument for pitch is the ASI tape. If any deviation from the desired speed is noted, make small pitch corrections by referencing the attitude indicator and validate the changes made with the airspeed tape. Utilize the airspeed trend indicator to judge if the airspeed is increasing and at what rate. Remember to trim off any control pressures.

The entry procedure for a constant rate descent is the same except the primary instrument for pitch is the VSI tape. The primary instrument for power is the ASI. When performing a constant rate descent while maintaining a specific airspeed, coordinated use of pitch and power is required. Any change in pitch directly affects the airspeed. Conversely, any change in airspeed has a direct impact on vertical speed as long as the pitch is being held constant.

Leveling Off

When leveling off from a descent with the intention of returning to cruise airspeed, first start by increasing the power to cruise prior to increasing the pitch back toward the level flight attitude. A technique used to determine how soon to start the level off is to lead the level off by an altitude corresponding to 10 percent of the rate of descent. For example, if the aircraft is descending at 1,000 fpm, start the level off 100 feet above the level off altitude. If the pitch attitude change is started late, there is a tendency to overshoot the desired altitude unless the pitch change is made with a rapid movement. Avoid making any rapid changes that could lead to control issues or spatial disorientation. Once in level pitch attitude, allow the aircraft to accelerate to the desired speed. Monitor the performance on the airspeed and altitude tapes. Make adjustments to the power in order to correct any deviations in the airspeed. Verify that the aircraft is maintaining level flight by cross-checking the altimeter tape. If deviations are noticed, make an appropriate smooth pitch change in order to arrive back at desired altitude. Any change in pitch requires a smooth coordinated change to the power setting. Monitor the airspeed in order to maintain the desired cruise airspeed.

To level off at a constant airspeed, the pilot must again determine when to start to increase the pitch attitude toward the level attitude. If pitch is the only item that is changing, airspeed varies due to the increase in drag as the aircraft’s pitch increases. A smooth coordinated increase in power needs to be made to a predetermined value in order to maintain speed. Trim the aircraft to relieve any control pressure that may have to be applied.

Common Errors in Straight Climbs and Descents

Climbing and descending errors usually result from but are not limited to the following errors:

- Overcontrolling pitch on beginning the climb. Aircraft familiarization is the key to achieving precise attitude instrument flying. Until the pilot becomes familiar with the pitch attitudes associated with specific airspeeds, the pilot must make corrections to the initial pitch settings. Changes do not produce instantaneous and stabilized results; patience must be maintained while the new speeds and vertical speed rates stabilize. Avoid the temptations to make a change and then rush into making another change until the first one is validated. Small changes produce more expeditious results and allow for a more stabilized flightpath. Large changes to pitch and power are more difficult to control and can further complicate the recovery process.

- Failure to increase the rate of instrument cross-check. Any time a pitch or power change is made, an increase in the rate a pilot cross-checks the instrument is required. A slow cross-check can lead to deviations in other flight attitudes.

- Failure to maintain new pitch attitudes. Once a pitch change is made to correct for a deviation, that pitch attitude must be maintained until the change is validated. Utilize trim to assist in maintaining the new pitch attitude. If the pitch is allowed to change, it is impossible to validate whether the initial pitch change was sufficient to correct the deviation. The continuous changing of the pitch attitude delays the recovery process.

- Failure to utilize effective trim techniques. If control pressures have to be held by the pilot, validation of the initial correction is impossible if the pitch is allowed to vary. Pilots have the tendency to either apply or relax additional control pressures when manually holding pitch attitudes. Trim allows the pilot to fly without holding pressure on the control yoke.

- Failure to learn and utilize proper power settings. Any time a pilot is not familiar with an aircraft’s specific pitch and power settings, or does not utilize them, a change in flightpaths takes longer. Learn pitch and power settings in order to expedite changing the flightpath.

- Failure to cross-check both airspeed and vertical speed prior to making adjustments to pitch and or power. It is possible that a change in one may correct a deviation in the other.

- Uncoordinated use of pitch and power during level offs. During level offs, both pitch and power settings need to be made in unison in order to achieve the desired results. If pitch is increased before adding power, additional drag is generated thereby reducing airspeed below the desired value.

- Failure to utilize supporting pitch instruments leads to chasing the VSI. Always utilize the attitude indicator as the control instrument on which to change the pitch.

- Failure to determine a proper lead time for level off from a climb or descent. Waiting too long can lead to overshooting the altitude.

- Ballooning—Failure to maintain forward control pressure during level off as power is increased. Additional lift is generated causing the nose of the aircraft to pitch up.