Safety Considerations

In the interest of safety and good habit pattern formation, there are certain basic flight safety practices and procedures that should be emphasized by the flight instructor, and adhered to by both instructor and learner, beginning with the very first dual instruction flight. These include, but are not limited to, collision avoidance procedures including proper scanning techniques and clearing procedures, runway incursion avoidance, stall awareness, positive transfer of controls, and flight deck workload management.

Collision Avoidance

All pilots should be alert to the potential for midair collision and impending loss of separation. The general operating and flight rules in 14 CFR part 91 set forth the concept of “see and avoid.” This concept requires that vigilance shall be maintained at all times by each person operating an aircraft regardless of whether the operation is conducted under IFR or VFR. Pilots should also keep in mind their responsibility for continuously maintaining a vigilant lookout regardless of the type of aircraft being flown and the purpose of the flight. Most midair collision accidents and reported near midair collision incidents occur in good VFR weather conditions and during the hours of daylight. Most of these accident/incidents occur within 5 miles of an airport and/or near navigation aids. [Figure 1]

The “see and avoid” concept relies on knowledge of the limitations of the human eye and the use of proper visual scanning techniques to help compensate for these limitations. Pilots should remain constantly alert to all traffic movement within their field of vision, as well as periodically scanning the entire visual field outside of their aircraft to ensure detection of conflicting traffic.

Remember that the performance capabilities of many aircraft, in both speed and rates of climb/descent, result in high closure rates limiting the time available for detection, decision, and evasive action. [Figure 2]

The probability of spotting a potential collision threat increases with the time spent looking outside, but certain techniques may be used to increase the effectiveness of the scan time. The human eyes tend to focus somewhere, even in a featureless sky. In order to be most effective, the pilot should shift glances and refocus at intervals. Most pilots do this in the process of scanning the instrument panel, but it is also important to focus outside to set up the visual system for effective target acquisition. Pilots should also realize that their eyes may require several seconds to refocus when switching views between items on the instrument panel and distant objects.Proper scanning requires the constant sharing of attention with other piloting tasks, thus it is easily degraded by psychological and physiological conditions such as fatigue, boredom, illness, anxiety, or preoccupation.Effective scanning is accomplished with a series of short, regularly-spaced eye movements that bring successive areas of the sky into the central visual field. Each movement should not exceed 10 degrees, and each area should be observed for at least 1 second to enable detection. Although horizontal back-and-forth eye movements seem preferred by most pilots, each pilot should develop a scanning pattern that is comfortable and adhere to it to assure optimum scanning.

Peripheral vision can be most useful in spotting collision threats from other aircraft. Each time a scan is stopped and the eyes are refocused, the peripheral vision takes on more importance because it is through this element that movement is detected. Apparent movement is usually the first perception of a collision threat and probably the most important because it is the discovery of a threat that triggers the events leading to proper evasive action. It is essential to remember that if another aircraft appears to have no relative motion, it is likely to be on a collision course. If the other aircraft shows no lateral or vertical motion, but is increasing in size, the observing pilot needs to take immediate evasive action to avoid a collision.

The importance of, and the proper techniques for, visual scanning should be taught at the very beginning of flight training. The competent flight instructor should be familiar with the visual scanning and collision avoidance information contained in AC 90-48, Pilots’ Role in Collision Avoidance, and the Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM).

There are many different types of clearing procedures. Most are centered around the use of clearing turns. The essential idea of the clearing turn is to be certain that the next maneuver is not going to proceed into another aircraft’s flightpath. Some pilot training programs have hard and fast rules, such as requiring two 90° turns in opposite directions before executing any training maneuver. Other types of clearing procedures may be developed by individual flight instructors. Whatever the preferred method, the flight instructor should teach the beginning learner an effective clearing procedure and insist on its use. The learner should execute the appropriate clearing procedure before all turns and before executing any training maneuver. Proper clearing procedures, combined with proper visual scanning techniques, are the most effective strategy for collision avoidance.

In case of pilot incapacitation, an installed Emergency Autoland (EAL) system may take control of an airplane, navigate to an airport, and land without additional human intervention. Currently, these systems take no evasive action in response to potential impact with another aircraft, although they transmit over the radio. Pilots should avoid the path of any aircraft under the control of an EAL or suspected as under the control of an EAL system. The Emergency Procedures section contains additional information about these systems.

Runway Incursion Avoidance

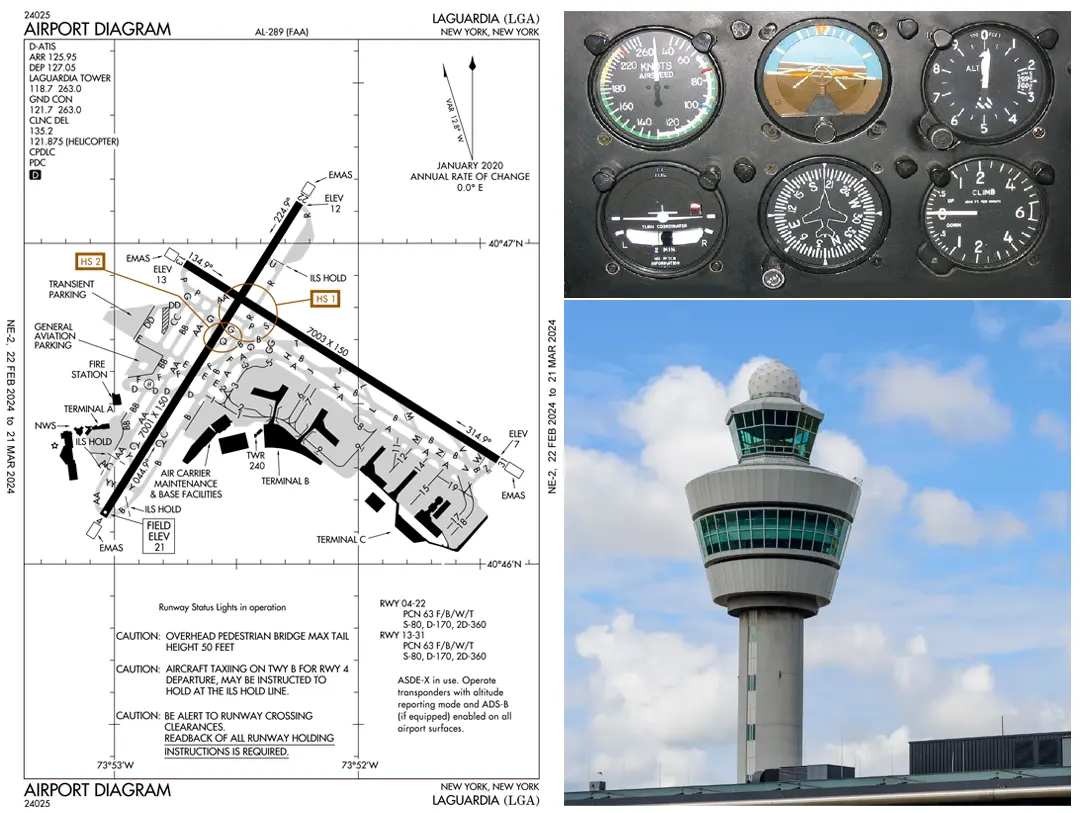

A runway incursion is any occurrence at an airport involving an aircraft, vehicle, person, or object on the ground that creates a collision hazard or results in a loss of separation with an aircraft taking off, landing, or intending to land. The three major areas contributing to runway incursions are communications, airport knowledge, and flight deck procedures for maintaining orientation. [Figure 3]

Taxi operations require constant vigilance by the entire flight crew, not just the pilot taxiing the airplane. During flight training, the instructor should emphasize the importance of vigilance during taxi operations. Both the learner and the flight instructor need to be continually aware of the movement and location of other aircraft and ground vehicles on the airport movement area. Many flight training activities are conducted at non-tower controlled airports. The absence of an operating airport control tower creates a need for increased vigilance on the part of pilots operating at those airports. [Figure 4]

Planning, clear communications, and enhanced situational awareness during airport surface operations reduces the potential for surface incidents. Safe aircraft operations can be accomplished and incidents eliminated if the pilot is properly trained early on and throughout their flying career on standard taxi operating procedures and practices. This requires the development of the formalized teaching of safe operating practices during taxi operations. The flight instructor is the key to this teaching. The flight instructor should instill in the learner an awareness of the potential for runway incursion, and should emphasize the runway incursion avoidance procedures. For more information and a list of additional references, refer to Airport Operations of the Aeronautical Knowledge section.

Stall Awareness

14 CFR part 61, section 61.87 (d)(10) and (e)(10) require that a student pilot who is receiving training for a single-engine or multiengine airplane rating or privileges, respectively, log flight training in stalls and stall recoveries prior to solo flight. [Figure 5]

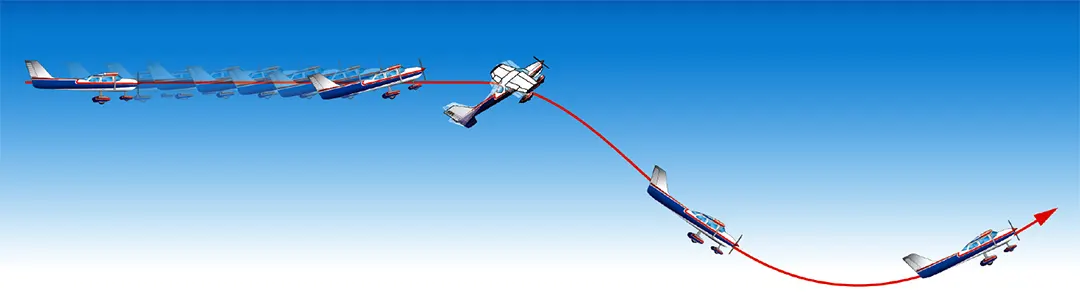

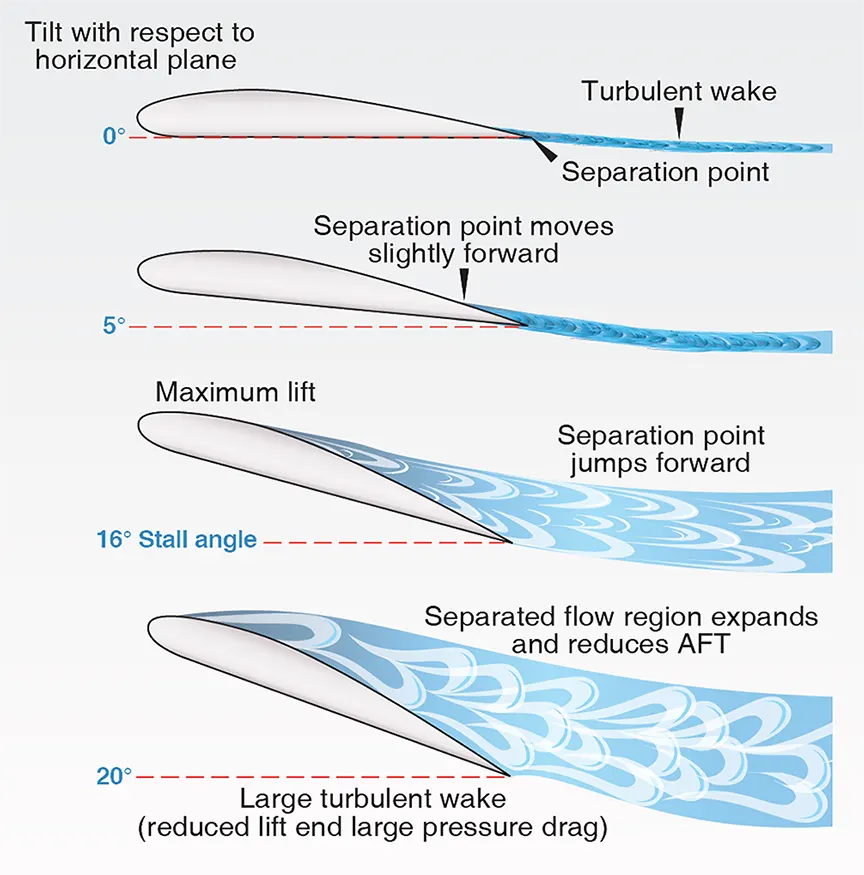

During this training, the flight instructor should emphasize that the direct cause of every stall is an excessive angle of attack (AOA). The student pilot should fully understand that there are several flight maneuvers that may produce an increase in the wing’s AOA, but the stall does not occur until the AOA becomes excessive. This critical AOA varies from 16°–20° depending on the airplane design. [Figure 6]

The flight instructor should emphasize that low speed is not necessary to produce a stall. The wing can be brought to an excessive AOA at any speed. High pitch attitude is not an absolute indication of proximity to a stall. Some airplanes are capable of vertical flight with a corresponding low AOA. Most airplanes are quite capable of stalling at a level or near level pitch attitude.The key to stall awareness is the pilot’s ability to visualize the wing’s AOA in any particular circumstance, and thereby be able to estimate his or her margin of safety above stall. This is a learned skill that should be acquired early in flight training and carried through the pilot’s entire flying career.The pilot should understand and appreciate factors such as airspeed, pitch attitude, load factor, relative wind, power setting, and aircraft configuration in order to develop a reasonably accurate mental picture of the wing’s AOA at any particular time. It is essential to safety of flight that pilots take into consideration this visualization of the wing’s AOA prior to entering any flight maneuver. Section, Basic Flight Maneuvers, discusses stalls in detail.

Use of Checklists

Checklists have been the foundation of pilot standardization and flight deck safety for years. [Figure 7] The checklist is a memory aid and helps to ensure that critical items necessary for the safe operation of aircraft are not overlooked or forgotten. Checklists need not be “do lists.” In other words, the proper actions can be accomplished, and then the checklist used to quickly ensure all necessary tasks or actions have been completed with emphasis on the “check” in checklist. However, checklists are of no value if the pilot is not committed to using them. Without discipline and dedication to using the appropriate checklists at the appropriate times, the odds are on the side of error. Pilots who fail to take the use of checklists seriously become complacent and begin to rely solely on memory.

The importance of consistent use of checklists cannot be overstated in pilot training. A major objective in primary flight training is to establish habit patterns that will serve pilots well throughout their entire flying career. The flight instructor should promote a positive attitude toward checklist usage, and the learner should realize its importance. At a minimum, prepared checklists should be used for the following phases of flight: [Figure 8]

- Preflight inspection

- Before engine start

- Engine starting

- Before taxiing

- Before takeoff

- After takeoff

- Cruise

- Descent

- Before landing

- After landing

- Engine shutdown and securing

During flight training, there should be a clear understanding between the learner and flight instructor of who has control of the aircraft. Prior to any flight, a briefing should be conducted that includes the procedures for the exchange of flight controls. The following three-step process for the exchange of flight controls is highly recommended.When a flight instructor wishes the learner to take control of the aircraft, he or she should say to the learner, “You have the flight controls.” The learner should acknowledge immediately by saying, “I have the flight controls.” The flight instructor should then confirm by again saying, “You have the flight controls.” Part of the procedure should be a visual check to ensure that the other person actually has the flight controls. When returning the controls to the flight instructor, the learner should follow the same procedure the instructor used when giving control to the learner. The learner should stay on the controls until the instructor says, “I have the flight controls.” There should never be any doubt as to who is flying the airplane at any time. Numerous accidents have occurred due to a lack of communication or misunderstanding as to who actually had control of the aircraft, particularly between learners and flight instructors. Establishing the above procedure during initial training ensures the formation of a very beneficial habit pattern.

Continuing Education

In many activities, the ability to receive feedback and continue learning contributes to safety and success. For example, professional athletes receive constant coaching. They practice various techniques to achieve their best. Medical professionals read journals, train, and master techniques to achieve better outcomes.

FAA WINGS Program

Compare continuous training and practice to 14 CFR part 61, section 61.56(c)(1) and (2), which allows for training and a sign-off within the previous 24 calendar months in order to act as a pilot in command. Many astute pilots realize that this regulation specifies a minimum requirement, and the path to enhanced proficiency, safety, and enjoyment of flying takes a higher degree of commitment such as using 14 CFR part 61, section 61.56(e). For this reason, many pilots keep their flight review up-to-date using the FAA WINGS program. The program provides continuing pilot education and contains interesting and relevant study materials that pilots can use all year round.

A pilot may create a WINGS account by logging on to www.faasafety.gov. This account gives the pilot access to the latest information concerning aviation technology and risk mitigation. It provides a means to document targeted skill development as a means to increase safety. As an added bonus, participants may receive a discount on certain flight insurance policies.