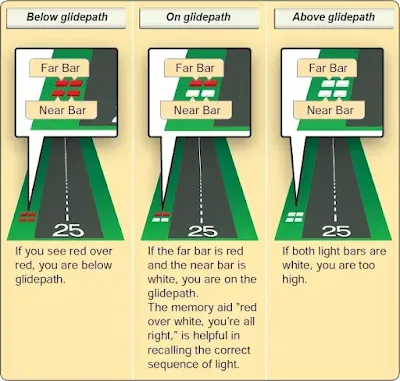

When approaching the airport to enter the traffic pattern and land, it is important that the runway lights and other airport lighting be identified as early as possible. If the airport layout is unfamiliar, sighting of the runway may be difficult until very close-in due to the maze of lights observed in the area. [Figure 1] A pilot should normally fly toward the rotating beacon until the lights outlining the runway are distinguishable. To fly a traffic pattern of proper size and direction, the runway threshold and runway-edge lights need to be positively identified. Once the airport lights are seen, these lights should be kept in sight throughout the approach.

|

| Figure 1. Use light patterns for orientation |

Distance may be deceptive at night due to limited lighting conditions. A lack of intervening references on the ground and the inability to compare the size and location of different ground objects cause this. This also applies to the estimation of altitude and speed. Consequently, more dependence should be placed on flight instruments, particularly the altimeter and the airspeed indicator. Monitoring the altimeter prevents flying too low for the distance from the airport. When entering the traffic pattern, the pilot should allow adequate time to complete the before-landing checklist. If the heading indicator contains a heading bug, setting it to the runway heading is an excellent reference for the pattern legs.

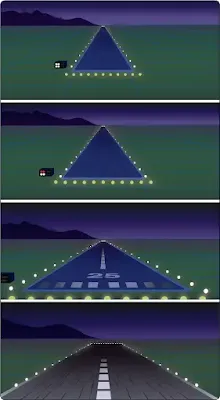

The pilot maintains the recommended airspeeds and executes the approach and landing in the same manner as during the day. A low, shallow approach is definitely inappropriate during a night operation. The altimeter and VSI should be constantly cross-checked against the airplane’s position along the base leg and final approach. A visual approach slope indicator (VASI) is an indispensable aid in establishing and maintaining a proper glide path. [Figure 2]

|

| Figure 2. VASI |

After turning onto the final approach and aligning the airplane midway between the two rows of runway-edge lights, the pilot should note and correct for any wind drift. Throughout the final approach, proper use of pitch and power helps to maintain a stabilized approach. Flaps are used as in a normal approach. Usually, halfway through the final approach, the landing light is turned on. The landing light is sometimes ineffective since the light beam will usually not reach the ground from higher altitudes. The light may even be reflected back into the pilot’s eyes by any existing haze, smoke, or fog. Safety considerations regarding local traffic and collision avoidance may overshadow these disadvantages.

The round out and touchdown is made in the same manner as in day landings. At night, the judgment of height, speed, and sink rate is impaired by the scarcity of observable objects in the landing area. An inexperienced pilot may have a tendency to round out too high. Continuing a constant approach descent until the landing lights reflect on the runway and tire marks on the runway can be seen clearly helps identify the point to begin the round out. At this point, the round out is started smoothly and the throttle gradually reduced to idle as the airplane is touching down. [Figure 3]

|

| Figure 3. Round out when tire marks are visible |

During landings without the use of landing lights, the round out may be started when the runway lights at the far end of the runway first appear to be rising higher than the nose of the airplane. This demands a smooth and very timely round out and requires that the pilot feel for the runway surface using power and pitch changes, as necessary, for the airplane to settle slowly to the runway. Blackout landings should always be included in night pilot training as an emergency procedure.