Icing

One of the greatest hazards to flight is aircraft icing. The instrument pilot must be aware of the conditions conducive to aircraft icing. These conditions include the types of icing, the effects of icing on aircraft control and performance, effects of icing on aircraft systems, and the use and limitations of aircraft deice and anti-ice equipment. Coping with the hazards of icing begins with preflight planning to determine where icing may occur during a flight and ensuring the aircraft is free of ice and frost prior to takeoff. This attention to detail extends to managing deice and anti-ice systems properly during the flight, because weather conditions may change rapidly, and the pilot must be able to recognize when a change of flight plan is required.

Types of Icing

Structural Icing

Structural icing refers to the accumulation of ice on the exterior of the aircraft. Ice forms on aircraft structures and surfaces when super-cooled droplets impinge on them and freeze. Small and/or narrow objects are the best collectors of droplets and ice up most rapidly. This is why a small protuberance within sight of the pilot can be used as an “ice evidence probe.” It is generally one of the first parts of the airplane on which an appreciable amount of ice forms. An aircraft’s tailplane is a better collector than its wings, because the tailplane presents a thinner surface to the airstream.

Induction Icing

Ice in the induction system can reduce the amount of air available for combustion. The most common example of reciprocating engine induction icing is carburetor ice. Most pilots are familiar with this phenomenon, which occurs when moist air passes through a carburetor venturi and is cooled. As a result of this process, ice may form on the venturi walls and throttle plate, restricting airflow to the engine. This may occur at temperatures between 20 °F (–7 °C) and 70 °F (21 °C). The problem is remedied by applying carburetor heat, which uses the engine’s own exhaust as a heat source to melt the ice or prevent its formation. On the other hand, fuel-injected aircraft engines usually are less vulnerable to icing but still can be affected if the engine’s air source becomes blocked with ice. Manufacturers provide an alternate air source that may be selected in case the normal system malfunctions.

Clear Ice

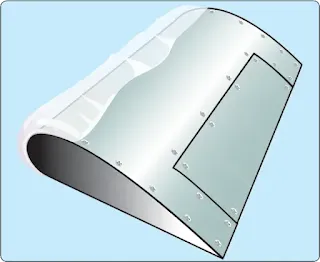

A glossy, transparent ice formed by the relatively slow freezing of super cooled water is referred to as clear ice. [Figure 1] The terms “clear” and “glaze” have been used for essentially the same type of ice accretion. This type of ice is denser, harder, and sometimes more transparent than rime ice. With larger accretions, clear ice may form “horns.”

|

| Figure 1. Clear ice |

|

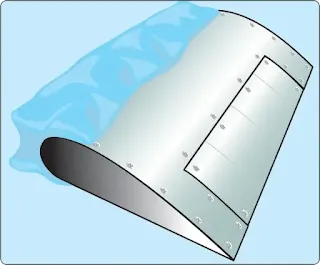

| Figure 2. Clear ice buildup with horns |

Rime Ice

|

| Figure 3. Rime ice |

Mixed Ice

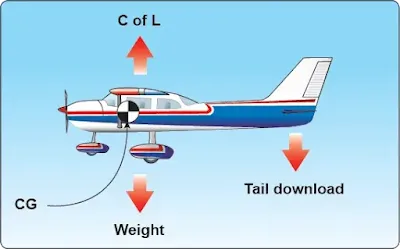

General Effects of Icing on Airfoils

|

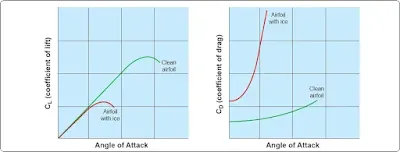

| Figure 4. Aerodynamic effects of icing |

|

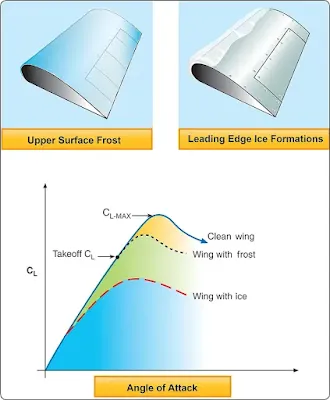

| Figure 5. Effect of ice and frost on lift |

|

| Figure 6. Downward force on the tailplane |

|

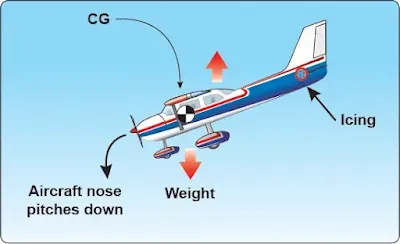

| Figure 7. Ice on the tailplane |

Piper PA-34-200T (Des Moines, Iowa)

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) determined the probable cause of the accident was the pilot’s failure to use the airplane’s deicing system, which resulted in an accumulation of empennage ice and a tailplane stall. Factors relating to this accident were the icing conditions and the pilot’s intentional flight into those known conditions.

Tailplane Stall Symptoms

Any of the following symptoms, occurring singly or in combination, may be a warning of tailplane icing:

- Elevator control pulsing, oscillations, or vibrations;

- Abnormal nose-down trim change;

- Any other unusual or abnormal pitch anomalies (possibly resulting in pilot induced oscillations);

- Reduction or loss of elevator effectiveness;

- Sudden change in elevator force (control would move nose-down if unrestrained); and

- Sudden uncommanded nose-down pitch.

If any of the above symptoms occur, the pilot should:

- Immediately retract the flaps to the previous setting and apply appropriate nose-up elevator pressure;

- Increase airspeed appropriately for the reduced flap extension setting;

- Apply sufficient power for aircraft configuration and conditions. (High engine power settings may adversely impact response to tailplane stall conditions at high airspeed in some aircraft designs. Observe the manufacturer’s recommendations regarding power settings.);

- Make nose-down pitch changes slowly, even in gusting conditions, if circumstances allow; and

- If a pneumatic deicing system is used, operate the system several times in an attempt to clear the tailplane of ice.

Once a tailplane stall is encountered, the stall condition tends to worsen with increased airspeed and possibly may worsen with increased power settings at the same flap setting. Airspeed, at any flap setting, in excess of the airplane manufacturer’s recommendations, accompanied by uncleared ice contaminating the tailplane, may result in a tailplane stall and uncommanded pitch down from which recovery may not be possible. A tailplane stall may occur at speeds less than the maximum flap extended speed (VFE).

Propeller Icing

Ice buildup on propeller blades reduces thrust for the same aerodynamic reasons that wings tend to lose lift and increase drag when ice accumulates on them. The greatest quantity of ice normally collects on the spinner and inner radius of the propeller. Propeller areas on which ice may accumulate and be ingested into the engine normally are anti-iced rather than deiced to reduce the probability of ice being shed into the engine.

Effects of Icing on Critical Aircraft Systems

In addition to the hazards of structural and induction icing, the pilot must be aware of other aircraft systems susceptible to icing. The effects of icing do not produce the performance loss of structural icing or the power loss of induction icing but can present serious problems to the instrument pilot. Examples of such systems are flight instruments, stall warning systems, and windshields.

Flight Instruments

Various aircraft instruments including the airspeed indicator, altimeter, and rate-of-climb indicator utilize pressures sensed by pitot tubes and static ports for normal operation.

When covered by ice these instruments display incorrect information thereby presenting serious hazard to instrument flight. Detailed information on the operation of these instruments and the specific effects of icing is presented in Flight Instruments section.

Stall Warning Systems

Stall warning systems provide essential information to pilots. These systems range from a sophisticated stall warning vane to a simple stall warning switch. Icing affects these systems in several ways resulting in possible loss of stall warning to the pilot. The loss of these systems can exacerbate an already hazardous situation. Even when an aircraft’s stall warning system remains operational during icing conditions, it may be ineffective because the wing stalls at a lower AOA due to ice on the airfoil.

Windshields

Accumulation of ice on flight deck windows can severely restrict the pilot’s visibility outside of the aircraft. Aircraft equipped for flight into known icing conditions typically have some form of windshield anti-icing to enable the pilot to see outside the aircraft in case icing is encountered in flight. One system consists of an electrically heated plate installed onto the airplane’s windshield to give the pilot a narrow band of clear visibility. Another system uses a bar at the lower end of the windshield to spray deicing fluid onto it and prevent ice from forming. On high performance aircraft that require complex windshields to protect against bird strikes and withstand pressurization loads, the heating element often is a layer of conductive film or thin wire strands through which electric current is run to heat the windshield and prevent ice from forming.

Antenna Icing

Because of their small size and shape, antennas that do not lay flush with the aircraft’s skin tend to accumulate ice rapidly. Furthermore, they often are devoid of internal anti-icing or deicing capability for protection. During flight in icing conditions, ice accumulations on an antenna may cause it to begin to vibrate or cause radio signals to become distorted and it may cause damage to the antenna. If a frozen antenna breaks off, it can damage other areas of the aircraft in addition to causing a communication or navigation system failure.