Climbs

For a given power setting and load condition, there is only one attitude that gives the most efficient rate of climb. The airspeed and climb power setting that determines this climb attitude are given in the performance data found in the POH/AFM. Details of the technique for entering a climb vary according to airspeed on entry and the type of climb (constant airspeed or constant rate) desired. (Heading and trim control are maintained as discussed in straight-and-level flight.)

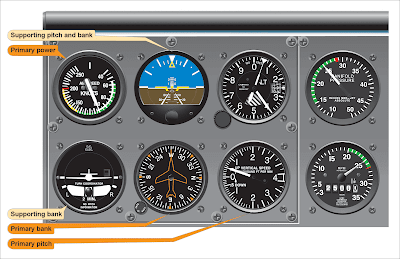

Entry

To enter a constant-airspeed climb from cruising airspeed, raise the miniature aircraft to the approximate nose-high indication for the predetermined climb speed. The attitude varies according to the type of airplane. Apply light backelevator pressure to initiate and maintain the climb attitude. The pressures vary as the airplane decelerates. Power may be advanced to the climb power setting simultaneously with the pitch change or after the pitch change is established and the airspeed approaches climb speed. If the transition from level flight to climb is smooth, the VSI shows an immediate trend upward, continues to move slowly, and then stops at a rate appropriate to the stabilized airspeed and attitude. (Primary and supporting instruments for the climb entry are shown in Figure 1.)

|

| Figure 1. Climb entry for constant airspeed climb |

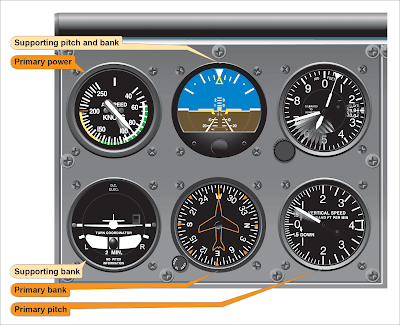

Once the airplane stabilizes at a constant airspeed and attitude, the ASI is primary for pitch and the heading indicator remains primary for bank. [Figure 2] Monitor the tachometer or manifold pressure gauge as the primary power instrument to ensure the proper climb power setting is being maintained. If the climb attitude is correct for the power setting selected, the airspeed will stabilize at the desired speed. If the airspeed is low or high, make an appropriately small pitch correction.

|

| Figure 2. Stabilized climb at constant airspeed |

To enter a constant airspeed climb, first complete the airspeed reduction from cruise airspeed to climb speed in straight-and-level flight. The climb entry is then identical to entry from cruising airspeed, except that power must be increased simultaneously to the climb setting as the pitch attitude is increased. Climb entries on partial panel are more easily and accurately controlled if entering the maneuver from climbing speed.

|

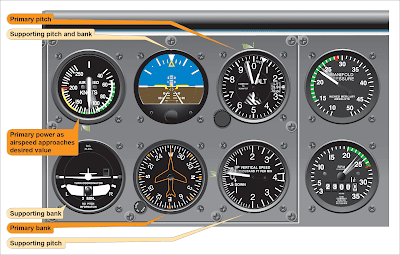

| Figure 3. Stabilized climb at constant rate |

Pitch and power corrections must be promptly and closely coordinated. For example, if the vertical speed is correct, but the airspeed is low, add power. As the power is increased, the miniature aircraft must be lowered slightly to maintain constant vertical speed. If the vertical speed is high and the airspeed is low, lower the miniature aircraft slightly and note the increase in airspeed to determine whether or not a power change is also necessary. [Figure 4] Familiarity with the approximate power settings helps to keep pitch and power corrections at a minimum.

|

| Figure 4. Airspeed low and vertical speed high—reduce pitch |

Leveling Off

To level off from a climb and maintain an altitude, it is necessary to start the level off before reaching the desired altitude. The amount of lead varies with rate of climb and pilot technique. If the airplane is climbing at 1,000 fpm, it continues to climb at a decreasing rate throughout the transition to level flight. An effective practice is to lead the altitude by 10 percent of the vertical speed shown (500 fpm/ 50-foot lead, 1,000 fpm/100-foot lead).

To level off at cruising airspeed, apply smooth, steady forward-elevator pressure toward level flight attitude for the speed desired. As the attitude indicator shows the pitch change, the vertical speed needle moves slowly toward zero, the altimeter needle moves more slowly, and the airspeed shows acceleration. [Figure 5] When the altimeter, attitude indicator, and VSI show level flight, constant changes in pitch and torque control have to be made as the airspeed increases. As the airspeed approaches cruising speed, reduce power to the cruise setting. The amount of lead depends upon the rate of acceleration of the airplane.

|

| Figure 5. Level off at cruising speed |

To level off at climbing airspeed, lower the nose to the pitch attitude appropriate to that airspeed in level flight. Power is simultaneously reduced to the setting for that airspeed as the pitch attitude is lowered. If power reduction is at a rate proportionate to the pitch change, airspeed will remain constant.

Descents

A descent can be made at a variety of airspeeds and attitudes by reducing power, adding drag, and lowering the nose to a predetermined attitude. The airspeed eventually stabilizes at a constant value. Meanwhile, the only flight instrument providing a positive attitude reference is the attitude indicator. Without the attitude indicator (such as during a partial panel descent), the ASI, altimeter, and VSI show varying rates of change until the airplane decelerates to a constant airspeed at a constant attitude. During the transition, changes in control pressure and trim, as well as cross-check and interpretation, must be accurate to maintain positive control.

Entry

The following method for entering descents is effective with or without an attitude indicator. First, reduce airspeed to a selected descent airspeed while maintaining straight-and-level flight, then make a further reduction in power (to a predetermined setting). As the power is adjusted, simultaneously lower the nose to maintain constant airspeed, and trim off control pressures.

During a constant airspeed descent, any deviation from the desired airspeed calls for a pitch adjustment. For a constant rate descent, the entry is the same, but the VSI is primary for pitch control (after it stabilizes near the desired rate), and the ASI is primary for power control. Pitch and power must be closely coordinated when corrections are made, as they are in climbs. [Figure 6]

|

| Figure 6. Constant airspeed descent, airspeed high—reduce power |

Leveling Off

The level off from a descent must be started before reaching the desired altitude. The amount of lead depends upon the rate of descent and control technique. With too little lead, the airplane tends to overshoot the selected altitude unless technique is rapid. Assuming a 500 fpm rate of descent, lead the altitude by 100–150 feet for a level off at an airspeed higher than descending speed. At the lead point, add power to the appropriate level flight cruise setting. [Figure 7] Since the nose tends to rise as the airspeed increases, hold forward elevator pressure to maintain the vertical speed at the descending rate until approximately 50 feet above the altitude, and then smoothly adjust the pitch attitude to the level flight attitude for the airspeed selected.

|

| Figure 7. Level off airspeed higher than descent airspeed |

To level off from a descent at descent airspeed, lead the desired altitude by approximately 50 feet, simultaneously adjusting the pitch attitude to level flight and adding power to a setting that holds the airspeed constant. [Figure 8] Trim off the control pressures and continue with the normal straight-and-level flight cross-check.

|

| Figure 8. Level off at descent airspeed |

Common Errors in Straight Climbs and Descents

Common errors result from the following faults:

- Overcontrolling pitch on climb entry. Until the pitch attitudes related to specific power settings used in climbs and descents are known, larger than necessary pitch adjustments are made. One of the most difficult habits to acquire during instrument training is to restrain the impulse to disturb a flight attitude until the result is known. Overcome the inclination to make a large control movement for a pitch change, and learn to apply small control pressures smoothly, cross-checking rapidly for the results of the change, and continuing with the pressures as instruments show the desired results. Small pitch changes can be easily controlled, stopped, and corrected; large changes are more difficult to control.

- Failure to vary the rate of cross-check during speed, power, or attitude changes or climb or descent entries.

- Failure to maintain a new pitch attitude. For example, raising the nose to the correct climb attitude, and as the airspeed decreases, either overcontrol and further increase the pitch attitude or allow the nose to lower. As control pressures change with airspeed changes, cross-check must be increased and pressures readjusted.

- Failure to trim off pressures. Unless the airplane is trimmed, there is difficulty in determining whether control pressure changes are induced by aerodynamic changes or by the pilot’s own movements.

- Failure to learn and use proper power settings.

- Failure to cross-check both airspeed and vertical speed before making pitch or power adjustments.

- Improper pitch and power coordination on slow-speed level offs due to slow cross-check of airspeed and altimeter indications.

- Failure to cross-check the VSI against the other pitch control instruments, resulting in chasing the vertical speed.

- Failure to note the rate of climb or descent to determine the lead for level offs, resulting in overshooting or undershooting the desired altitude.

- Ballooning (allowing the nose to pitch up) on level offs from descents, resulting from failure to maintain descending attitude with forward-elevator pressure as power is increased to the level flight cruise setting.

- Failure to recognize the approaching straight-and-level flight indications as level off is completed. Maintain an accelerated cross-check until positively established in straight-and-level flight.