Compiling and maintaining a worldwide airborne navigation database is a large and complex job. Within the United States, the FAA sources give the database providers information, in many different formats, which must be analyzed, edited, and processed before it can be coded into the database. In some cases, data from outside the United States must be translated into English so it may be analyzed and entered into the database. Once the data is coded, it must be continually updated and maintained.

Once the FAA notifies the database provider that a change is necessary, the update process begins. The change is incorporated into a 28-day airborne database revision cycle based on its assigned priority. If the information does not reach the coding phase prior to its cutoff date (the date that new aeronautical information can no longer be included in the next update), it is held out of revision until the next cycle. The cutoff date for aeronautical databases is typically 21 days prior to the effective date of the revision.

The integrity of the data is ensured through a process called cyclic redundancy check (CRC). A CRC is an error detection algorithm capable of detecting small bit-level changes in a block of data. The CRC algorithm treats a data block as a single, large binary value. The data block is divided by a fixed binary number called a generator polynomial whose form and magnitude is determined based on the level of integrity desired. The remainder of the division is the CRC value for the data block. This value is stored and transmitted with the corresponding data block. The integrity of the data is checked by reapplying the CRC algorithm prior to distribution.

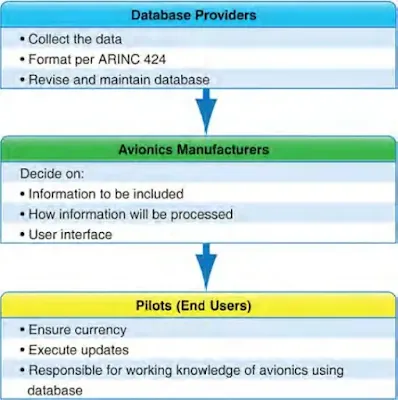

Role of the Avionics Manufacturer

When avionics manufacturers develop a piece of equipment that requires an airborne navigation database, they typically form an agreement with a database provider to supply the database for that new avionics platform. It is up to the manufacturer to determine what information to include in the database for their system. In some cases, the navigation data provider has to significantly reduce the number of records in the database to accommodate the storage capacity of the manufacturer’s new product, which means that the database may not contain all procedures.

Another important fact to remember is that although there are standard naming conventions included in the ARINC 424 specification, each manufacturer determines how the names of fixes and procedures are displayed to the pilot. This means that although the database may specify

the approach identifier field for the VOR/DME Runway 34 approach at Eugene Mahlon Sweet Airport (KEUG) in Eugene, Oregon, as “V34,” different avionics platforms may display the identifier in any way the manufacturer deems appropriate. For example, a GPS produced by one manufacturer might display the approach as “VOR 34,” whereas another might refer to the approach as “VOR/DME 34,” and an FMS produced by another manufacturer may refer to it as “VOR34.” [Figure 1]

|

| Figure 1. Naming conventions of three different systems for the VOR 34 Approach |

Users Role

Like paper charts, airborne navigation databases are subject to revision. According to 14 CFR Part 91, § 91.503, the end user (operator) is ultimately responsible for ensuring that data meets the quality requirements for its intended application. Updating data in an aeronautical database is considered to be maintenance and all Part 91 operators may update databases in accordance with 14 CFR Part 91, § 43.3(g). Parts 121, 125, and 135 operators must update databases in accordance with their approved maintenance program. For Part 135 helicopter operators, this includes maintenance by the pilot in accordance with 14 CFR Part 43, § 43.3(h).

|

| Figure 2. Database rolls |