Go-Around

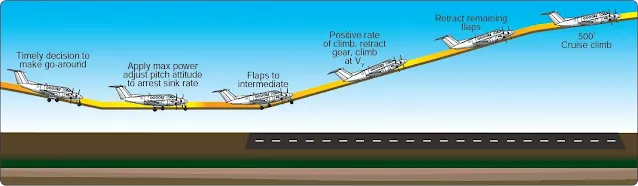

When the decision to go around is made, the throttles should be advanced to takeoff power. With adequate airspeed, the airplane should be placed in a climb pitch attitude. These actions, which are accomplished simultaneously, arrest the sink rate and place the airplane in the proper attitude for transition to a climb. The initial target airspeed is VY or VX if obstructions are present. With sufficient airspeed, the flaps should be retracted from full to an intermediate position and the landing gear retracted when there is a positive rate of climb and no chance of runway contact. The remaining flaps should then be retracted. [Figure]

|

| Go-around procedure |

If the go-around was initiated due to conflicting traffic on the ground or aloft, the pilot should maneuver to the side so as to keep the conflicting traffic in sight. This may involve a shallow bank turn to offset and then parallel the runway/landing area.

If the airplane was in trim for the landing approach when the go-around was commenced, it soon requires a great deal of forward elevator/stabilator pressure as the airplane accelerates away in a climb. The pilot should apply appropriate forward pressure to maintain the desired pitch attitude. Trim should be commenced immediately. The Balked Landing checklist should be reviewed as work load permits.

Flaps should be retracted before the landing gear for two reasons. First, on most airplanes, full flaps produce more drag than the extended landing gear. Secondly, the airplane tends to settle somewhat with flap retraction, and the landing gear should be down in the event of an inadvertent, momentary touchdown.

Many multiengine airplanes have a landing gear retraction speed significantly less than the extension speed. Care should be exercised during the go-around not to exceed the retraction speed. If the pilot desires to return for a landing, it is essential to re-accomplish the entire Before Landing checklist. An interruption to a pilot’s habit patterns, such as a go-around, is a classic scenario for a subsequent gear up landing.

The preceding discussion about doing a go-around assumes that the maneuver was initiated from normal approach speeds or faster. If the go-around was initiated from a low airspeed, the initial pitch up to a climb attitude must be tempered with the necessity of maintaining adequate flying speed throughout the maneuver. Examples of where this applies include a go-around initiated from the landing round out or recovery from a bad bounce, as well as a go-around initiated due to an inadvertent approach to a stall. The first priority is always to maintain control and obtain adequate flying speed. A few moments of level or near level flight may be required as the airplane accelerates up to climb speed.

Rejected Takeoff

A takeoff can be rejected for the same reasons a takeoff in a single-engine airplane would be rejected. Once the decision to reject a takeoff is made, the pilot should promptly close both throttles and maintain directional control with the rudder, nosewheel steering, and brakes. Aggressive use of rudder, nosewheel steering, and brakes may be required to keep the airplane on the runway. Particularly, if an engine failure is not immediately recognized and accompanied by prompt closure of both throttles. However, the primary objective is not necessarily to stop the airplane in the shortest distance, but to maintain control of the airplane as it decelerates. In some situations, it may be preferable to continue into the overrun area under control, rather than risk directional control loss, landing gear collapse, or tire/brake failure in an attempt to stop the airplane in the shortest possible distance.