Straight-and-level flight is flight in which heading and altitude are maintained. The other fundamentals are derived as variations from straight-and-level flight, and the need to form proper and effective skills in flying straight and level should be understood. The ability to perform straight-and-level flight results from repetition and practice. A high level of skill results when the pilot perceives outside references, takes mental snap shots of the flight instruments, and makes effective, timely, and proportional corrections from unintentional slight turns, descents, and climbs.

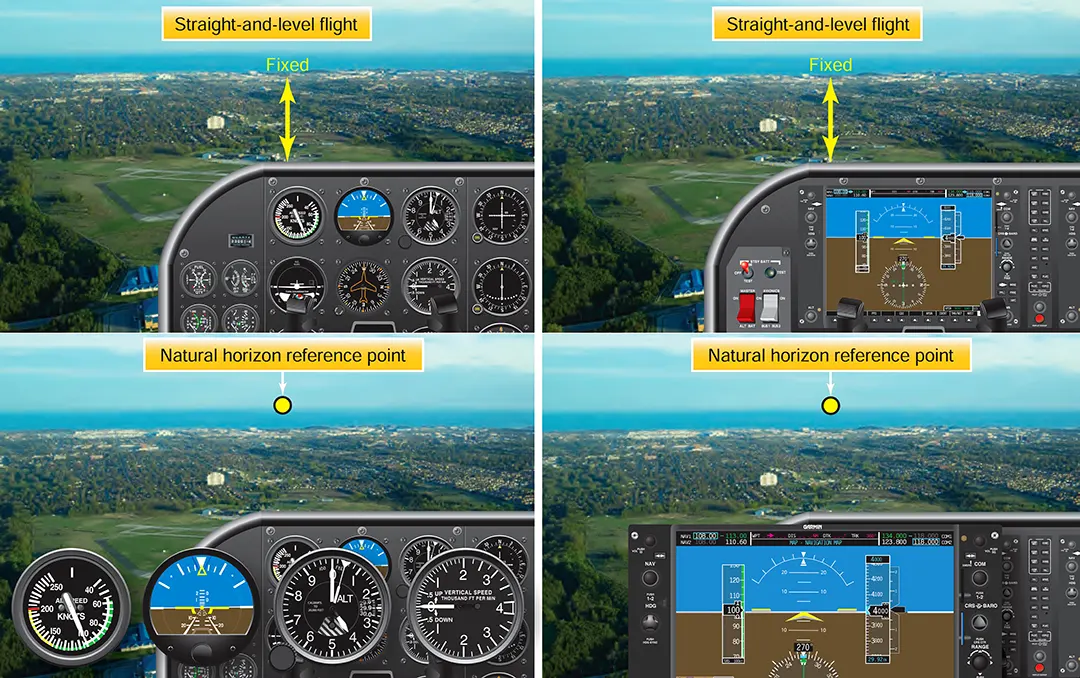

Straight-and-level flight is a matter of consciously fixing the relationship of a reference point on the airplane in relation to the natural horizon. [Figure 1] The establishment of these reference points should be initiated on the ground as they depend on the pilot’s seating position, height, and posture. The pilot should sit in a normal manner with the seat position adjusted, such that the pilot sees adequately over the instrument panel while being able to fully depress the rudder pedals without straining or reaching.

A flight instructor may use a dry erase marker or removable tape to make reference lines on the windshield or cowling to help the beginner pilot establish visual reference points. Vertical reference lines are best established on the ground, such as when the airplane is placed on a marked centerline, with the beginner pilot seated in proper position. Horizontal reference lines are best established with the airplane in flight, such as during slow flight and cruise configurations. The horizon reference point is always the same, no matter what altitude, since the point is always on the horizon, although the distance to the horizon will be further as altitude increases. There are multiple horizontal reference lines due to varying pitch attitude requirements; however, these teaching aids are generally needed for only a short period until the beginning pilot understands where and when to look while maneuvering the airplane.

Straight Flight

Maintaining a constant direction or heading is accomplished by visually checking the relationship of the airplane’s wingtips to the natural horizon. Depending on whether the airplane is a high wing or low wing, both wingtips should be level and equally above or below the natural horizon. Any necessary bank corrections are made with the pilot’s coordinated use of ailerons and rudder. [Figure 2] The pilot should understand that anytime the wings are banked, the airplane turns. The objective of straight flight is to detect and correct small deviations, necessitating minor flight control corrections. The bank attitude information can also be obtained from a quick scan of the attitude indicator (which shows the position of the airplane’s wings relative to the horizon) and the heading indicator (which indicates if the airplane is off the desired heading).

It is possible to maintain straight flight by simply exerting the necessary pressure with the ailerons or rudder independently in the desired direction of correction. However, the practice of using the ailerons and rudder independently is not correct and makes precise control of the airplane difficult. The correct bank flight control movement requires the coordinated use of ailerons and rudder. Straight-and-level flight requires almost no application of flight control pressures if the airplane is properly trimmed and the air is smooth. For that reason, the pilot should not form the habit of unnecessarily moving the flight controls. The pilot needs to learn to recognize when corrections are necessary and then to make a measured flight control response precisely, smoothly, and accurately.

Pilots may tend to look out to one side continually, generally to the left due to the pilot’s left seat position and consequently focus attention in that direction. This not only gives a restricted angle from which the pilot is to observe but also causes the pilot to exert unconscious pressure on the flight controls in that direction. It is also important that the pilot not fixate in any one direction and continually scan outside the airplane, not only to ensure that the airplane’s attitude is correct, but also to ensure that the pilot is considering other factors for safe flight. Continually observing both wingtips has advantages other than being the only positive check for leveling the wings. This includes looking for aircraft traffic, terrain and weather influences, and maintaining overall situational awareness.

Straight flight allows flying along a line. For outside references, the pilot selects a point on the horizon aligned with another point ahead. If those two points stay in alignment, the airplane will track the line formed by the two points. A pilot can also hold a course in VFR by tracking to a point in front of a compass or magnetic direction indicator, with only glances at the instrument or indicator to ensure being on course. The reliance on a surface point does not work when flying over water or flat snow covered surfaces. In these conditions, the pilot should rely on the magnetic heading indication.

Level Flight

In learning to control the airplane in level flight, it is important that the pilot be taught to maintain a light touch on the flight controls using fingers rather than the common problem of a tight-fisted palm wrapped around the flight controls. The pilot should exert only enough pressure on the flight controls to produce the desired result. The pilot should learn to associate the apparent movement of the references with the control pressures which produce attitude movement. As a result, the pilot can develop the ability to adjust the change desired in the airplane’s attitude by the amount and direction of pressures applied to the flight controls without the pilot excessively referring to instrument or outside references for each minor correction.

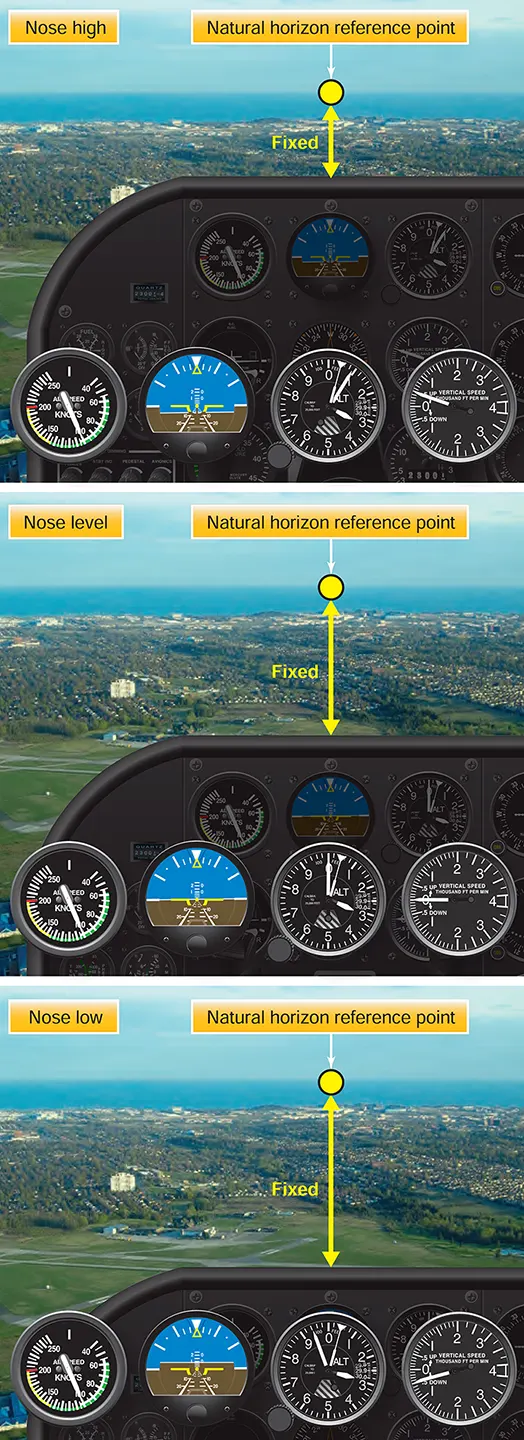

The pitch attitude for level flight is first obtained by the pilot being properly seated, selecting a point toward the airplane’s nose as a reference, and then keeping that reference point in a fixed position relative to the natural horizon. [Figure 3]

The principles of attitude flying require that the reference point to the natural horizon position should be cross-checked against the flight instruments to determine if the pitch attitude is correct. If trending away from the desired altitude, the pitch attitude should be readjusted in relation to the natural horizon and then the flight instruments crosschecked to determine if altitude is now being corrected or maintained. In level flight maneuvers, the terms “increase the back pressure” or “increase pitch attitude” implies raising the airplane’s nose in relation to the natural horizon and the terms “decreasing the pitch attitude” or “decrease pitch attitude” means lowering the nose in relation to the natural horizon. The pilot’s primary reference is the natural horizon.

For all practical purposes, the airplane’s airspeed remains constant in straight-and-level flight if the power setting is also constant. Intentional airspeed changes, by increasing or decreasing the engine power, provide proficiency in maintaining straight-and-level flight as the airplane’s airspeed is changing. Pitching moments may also be generated by extension and retraction of flaps, landing gear, and other drag producing devices, such as spoilers. Exposure to the effect of the various configurations should be covered in any specific airplane checkout.

Common Errors

A common error of a beginner pilot is attempting to hold the wings level by only observing the airplane’s nose. Using this method, the nose’s short horizontal reference line can cause slight deviations to go unnoticed. However, deviations from level flight are easily recognizable when the pilot references the wingtips and, as a result, the wingtips should be the pilot’s primary reference for maintaining level bank attitude. This technique also helps eliminate the potential for flying the airplane with one wing low and correcting heading errors with the pilot holding opposite rudder pressure. A pilot with a bad habit of dragging one wing low and compensating with opposite rudder pressure will have difficulty mastering other flight maneuvers.

Common errors include:

- Attempting to use improper pitch and bank refeequent flights.

- Forgetting the location of preselected reference points on subsequent flights.

- Attempting to establish or correct airplane attitude using flight instruments rather than the natural horizon.

- “Chasing” the flight instruments rather than adhering to the principles of attitude flying.

- Mechanically pushing or pulling on the flight controls rather than exerting accurate and smooth pressure.

- Not scanning outside the aircraft for other traffic and weather and terrain influences.

- A tight palm grip on the flight controls resulting in a desensitized feeling of the hand and fingers.

- Overcontrolling the airplane.

- Habitually flying with one wing low or maintaining directional control using only the rudder control.

- Failure to make timely and measured control inputs after a deviation from straight-and-level.

- Inadequate attention to sensory inputs in developing feel for trence points on the airplane to establish attitude.