Chandelle

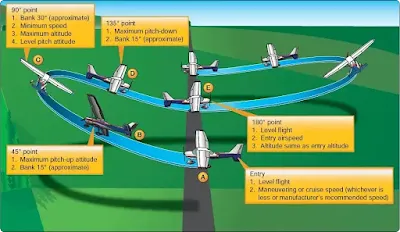

A chandelle is a maximum performance, 180° climbing turn that begins from approximately straight-and-level flight and concludes with the airplane in a wings-level, nose-high attitude just above stall speed. [Figure 1] The goal is to gain the most altitude possible for a given bank angle and power setting; however, the standard used to judge the maneuver is not the amount of altitude gained, but rather the pilot’s proficiency as it pertains to maximizing climb performance for the power and bank selected, as well as the skill demonstrated.

|

| Figure 1. Chandelle |

A chandelle is best described in two specific phases: the first 90° of turn and the second 90° of turn. The first 90° of turn is described as constant bank and continuously increasing pitch; and the second 90° as constant pitch and continuously decreasing bank. During the first 90°, the pilot will set the bank angle, increase power, and increase pitch attitude at a rate such that maximum pitch-up occurs at the completion of the first 90°. The maximum pitch-up attitude achieved at the 90° mark is held for the remainder of the maneuver. If the pitch attitude is set too low, the airplane’s airspeed will never decrease to just above stall speed. If the pitch attitude is set too high, the airplane may aerodynamically stall prior to completion of the maneuver. Starting at the 90° point, and while maintaining the pitch attitude set at the end of the first 90°, the pilot begins a slow and coordinated constant rate rollout so as to have the wings level when the airplane is at the 180° point. If the rate of rollout is too rapid or sluggish, the airplane either exceeds the 180° turn or does not complete the turn as the wings come level to the horizon.

Prior to starting the chandelle, the flaps and landing gear (if retractable) should be in the UP position. The chandelle is initiated by properly clearing the airspace for air traffic and hazards. The maneuver should be entered from straight-and-level flight or a shallow dive at an airspeed recommended by the manufacturer—in many cases this is the airplane’s design maneuvering speed (VA) or operating maneuvering speed (VO). [Figure 1A] After the appropriate entry airspeed has been established, the chandelle is started by smoothly entering a coordinated turn to the desired angle of bank. Once the bank angle is established, which is generally 30°, a climbing turn should be started by smoothly applying elevator back pressure at a constant rate while simultaneously increasing engine power to the recommended setting. In airplanes with a fixed-pitch propeller, the throttle should be set so as to not exceed rotations per minute (rpm) limitations. In airplanes with constant-speed propellers, power may be set at the normal cruise or climb setting as appropriate. [Figure 1B]

As airspeed decreases during the chandelle, left-turning tendencies, such as P-factor, have greater effect. As airspeed decreases, right rudder pressure is progressively increased to ensure that the airplane remains in coordinated flight. The pilot maintains coordinated flight by sensing physical slipping or skidding, by glancing at the ball in the turn-and-slip or turn coordinator, and by using appropriate control pressures.At the 90° point, the pilot should begin to smoothly roll out of the bank at a constant rate while maintaining the pitch attitude attained at the end of the first 90°. While the angle of bank is fixed during the first 90°, recall that as airspeed decreases, the overbanking tendency increases. [Figure 1C] As a result, proper use of the ailerons allows the bank to remain at a fixed angle until rollout is begun at the start of the final 90°. As the rollout continues, the vertical component of lift increases. However, as speed continues to decrease, a slight increase of elevator back pressure is required to keep the pitch attitude from decreasing.

When the airspeed is slowest, near the completion of the chandelle, right rudder pressure is significant, especially when rolling out from a left chandelle due to left adverse yaw and left-turning tendencies, such as P-factor. [Figure 1D] When rolling out from a right chandelle, the yawing moment is to the right, which partially cancels some of the left-turning tendency’s effect. Depending on the airplane, either very little left rudder or a reduction in right rudder pressure is required during the rollout from a right chandelle. At the completion of 180° of turn, the wings should be level to the horizon, the airspeed should be just above the power-on stall speed, and the airplane’s pitch-high attitude should be held momentarily. [Figure 1E]

Once the airplane is in controlled flight, the pitch attitude may be reduced and the airplane returned to straight-and-level cruise flight.

Common errors when performing chandelles are:

- Not clearing the area

- Initial bank is too shallow resulting in a stall

- Initial bank is too steep resulting in failure to gain maximum performance

- Allowing the bank angle to increase after initial establishment

- Not starting the recovery at the 90° point in the turn

- Allowing the pitch attitude to increase as the bank is rolled out during the second 90° of turn

- Leveling the wings prior to the 180° point being reached

- Pitch attitude is low on recovery resulting in airspeed well above stall speed

- Application of flight control pressures is not smooth

- Poor flight control coordination

- Stalling at any point during the maneuver

- Execution of a steep turn instead of a climbing maneuver

- Not scanning for other traffic during the maneuver

- Performing by reference to the instruments rather than visual references

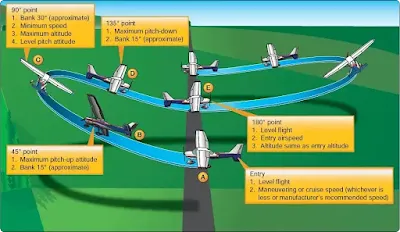

Lazy Eight

The lazy eight is a maneuver that is designed to develop the proper coordination of the flight controls across a wide range of airspeeds and attitudes. It is the only standard flight training maneuver in which flight control pressures are constantly changing. In an attempt to simplify the discussion about this maneuver, the lazy eight can be loosely compared to the ground reference maneuver, S-turns across the road. Recall that S-turns across the road are made of opposing 180° turns. For example, first a 180° turn to the right, followed immediately by a 180° turn to the left. The lazy eight adds both a climb and descent to each 180° segment. The first 90° is a climb; the second 90° is a descent. [Figure 2]

|

| Figure 2. Lazy eight |

The previous description of a lazy eight and figure 2 describe how a lazy eight looks from outside the flight deck and describes it as two 180° turns with altitude changes. How does it look from the pilot’s perspective? Think of the longitudinal axis of the airplane as a pencil, which draws on whatever it points to. During this maneuver, the longitudinal axis of the airplane traces a symmetrical eight on its side with segments of the eight above and below the horizon, and it takes both 180° turns to form both loops of an eight. The first 90° of the first 180° turn traces the upper portion of one of the loops. The second 90° portion of the second 180° turn traces the lower portion of that loop at the end of the maneuvuer. The second 90° of the first 180° turn and the first 90° of the second 180° turn complete the other loop of the eight. The sensation of using the airplane to slowly draw this symbol gives the maneuver its name.To aid in the performance of the lazy eight’s symmetrical climbing/descending turns, the pilot selects prominent reference points on the natural horizon. The reference points selected should be at 45°, 90°, and 135° from the direction in which the maneuver is started for each 180° turn. With the general concept of climbing and descending turns grasped, specifics of the lazy eight can then be discussed.

Shown in Figure 2A, from level flight a gradual climbing turn is begun in the direction of the 45° reference point. The climbing turn should be planned and controlled so that the maximum pitch-up attitude is reached at the 45° point with an approximate bank angle of 15°. [Figure 2B] As the pitch attitude is raised, the airspeed decreases, which causes the rate of turn to increase. As such, the lazy eight should begin with a slow rate of roll as the combination of increasing pitch and increasing bank may cause the rate of turn to be so rapid that the 45° reference point will be reached before the highest pitch attitude is attained. At the 45° reference point, the pitch attitude should be at the maximum pitch-up selected for the maneuver while the bank angle is slowly increasing. Beyond the 45° reference point, the pitch-up attitude should begin to decrease slowly toward the horizon until the 90° reference point is reached where the pitch attitude passes through level.The lazy eight requires substantial skill in coordinating the aileron and rudder; therefore, some discussion about coordination is warranted. As pilots understand, the purpose of the rudder is to maintain coordination; slipping or skidding is to be avoided. Pilots should remember that since the airspeed is still decreasing as the airplane is climbing; additional right rudder pressure should be applied to counteract left-turning tendencies, such as P-factor. As the airspeed decreases, right rudder pressure should be gradually applied to counteract yaw at the apex of the lazy eight in both the right and left turns; however, additional right rudder pressure is required when using right aileron control pressure. When displacing the ailerons for more lift on the left wing, left adverse yaw augments with the left-yawing P-factor in an attempt to yaw the nose to the left. In contrast, in left climbing turns or rolling to the left, the left yawing P-factor tends to cancel the effects of adverse yaw to the right; consequently, less right rudder pressure is required. These concepts can be difficult to remember; however, to simplify, rolling right at low airspeeds and high-power settings requires substantial right rudder pressures.

At the lazy eight’s 90° reference point, the bank angle should also have reached its maximum angle of approximately 30°. [Figure 2C] The airspeed should be at its minimum, just about 5 to 10 knots above stall speed, with the airplane’s pitch attitude passing through level flight. Coordinated flight at this point requires that, in some flight conditions, a slight amount of opposite aileron pressure may be required to prevent the wings from overbanking while maintaining rudder pressure to cancel the effects of left-turning tendencies.

The pilot should not hesitate at the 90° point but should continue to maneuver the airplane into a descending turn. The rollout from the bank should proceed slowly while the airplane’s pitch attitude is allowed to decrease. When the airplane has turned 135°, the airplane should be in its lowest pitch attitude. [Figure 2D] Pilots should remember that the airplane’s airspeed is increasing as the airplane’s pitch attitude decreases; therefore, maintaining proper coordination will require a decrease in right rudder pressure. As the airplane approaches the 180° point, it is necessary to progressively relax rudder and aileron pressure while simultaneously raising pitch and roll to level flight. As the rollout is being accomplished, the pilot should note the amount of turn remaining and adjust the rate of rollout and pitch change so that the wings and nose are level at the original airspeed just as the 180° point is reached.

Upon arriving at 180° point, a climbing turn should be started immediately in the opposite direction toward the preselected reference points to complete the second half of the lazy eight in the same manner as the first half. [Figure 2E]

Power should be set so as not to enter the maneuver at an airspeed that would exceed manufacturer’s recommendations, which isgenerally no greater than VA or VO. Power and bank angle have significant effect on the altitude gained or lost; if excess power is used for a given bank angle, altitude is gained at the completion of the maneuver; however, if insufficient power is used for a given bank angle, altitude is lost.

Common errors when performing lazy eights are:

- Not clearing the area

- Maneuver is not symmetrical across each 180°

- Inadequate or improper selection or use of 45°, 90°, 135° references

- Ineffective planning

- Gain or loss of altitude at each 180° point

- Poor control at the top of each climb segment resulting in the pitch rapidly falling through the horizon

- Airspeed or bank angle standards not met

- Control roughness

- Poor flight control coordination

- Stalling at any point during the maneuver

- Execution of a steep turn instead of a climbing maneuver

- Not scanning for other traffic during the maneuver

- Performing by reference to the flight instruments rather than visual references