It is beyond the scope of this site to incorporate a course of training in basic attitude instrument flying. This information is contained in the Instrument Flying section. Certain pilot certificates and/or associated ratings require training in instrument flying and a demonstration of specific instrument flying tasks on the practical test.

Pilots and flight instructors should refer to the Instrument Flying section for guidance in the performance of these tasks and to the appropriate airman certification standards (ACS) for information on the evaluation of tasks performed for the particular certificate level and/or rating. The pilot should remember, however, that unless these tasks are practiced on a continuing and regular basis, skill erosion begins almost immediately. In a very short time, the pilot’s assumed level of confidence is much higher than the performance he or she is actually able to demonstrate should the need arise.

Accident statistics show that the pilot who has not been trained in attitude instrument flying, or one whose instrument skills have eroded, lose control of the airplane in about 10 minutes once forced to rely solely on instrument references. The purpose of this section is to provide guidance on practical emergency measures to maintain airplane control for a limited period of time in the event a VFR pilot encounters instrument meteorological conditions (IMC). The main goal is not precision instrument flying; rather, it is to help the VFR pilot keep the airplane under adequate control until suitable visual references are regained.

The first steps necessary for surviving an encounter with IMC by a VFR pilot are as follows:

- Recognition and acceptance of the seriousness of the situation and the need for immediate remedial action

- Maintaining control of the airplane

- Obtaining the appropriate assistance to get the airplane safely on the ground

Recognition

Anytime a VFR pilot is unable to maintain airplane attitude control by reference to the natural horizon, the condition is considered to be IMC regardless of the circumstances or the prevailing weather conditions. Whether the cause is inadventent or intentional, the VFR pilot is, in effect, in IMC if unable to navigate or establish geographical position by visual reference to landmarks on the surface. These situations should be accepted by the pilot involved as a genuine emergency requiring appropriate action.

Pilots should understand that unless they are trained, qualified, and current in the control of an airplane solely by reference to flight instruments, they will be unable to do so for any length of time. Many hours of VFR flying using the attitude indicator as a reference for airplane control may lull pilots into a false sense of security based on an overestimation of their personal ability to control the airplane solely by instrument references. In VFR conditions, even though the pilot believes the instrument references will be easy to use, the pilot also receives an overview of the natural horizon and may subconsciously rely on it more than the attitude indicator. If the natural horizon were to suddenly disappear, the untrained instrument pilot would be subject to vertigo, spatial disorientation, and inevitable control loss.

Maintaining Airplane Control

Once the pilot recognizes and accepts the situation, he or she should understand that the only way to control the airplane safely is by using and trusting the flight instruments. Attempts to control the airplane partially by reference to flight instruments while searching outside of the airplane for visual confirmation of the information provided by those instruments results in inadequate airplane control. This may be followed by spatial disorientation and complete control loss.

The most important point to be stressed is that the pilot should not panic. The task at hand may seem overwhelming, and the situation may be compounded by extreme apprehension. However, the pilot should make a conscious effort to relax. The pilot needs to understand the most important concern—in fact the only concern at this point—is to keep the wings level. An uncontrolled turn or bank usually leads to difficulty in achieving the objectives of any desired flight condition, but good bank control has the effect of making pitch control much easier.

The pilot should remember that a person cannot feel control pressures with a tight grip on the controls. Relaxing and learning to “control with the eyes and the brain,” instead of only the muscles usually takes considerable conscious effort.

The pilot needs to believe what the flight instruments show about the airplane’s attitude regardless of what the natural senses tell. The vestibular sense (motion sensing by the inner ear) can and will confuse the pilot. Because of inertia, the sensory areas of the inner ear cannot detect slight changes in airplane attitude, nor can they accurately sense attitude changes that occur at a uniform rate over a period of time. On the other hand, false sensations are often generated, leading the pilot to believe the attitude of the airplane has changed when, in fact, it has not. These false sensations result in the pilot experiencing spatial disorientation.

Attitude Control

An airplane is, by design, an inherently stable platform and, except in turbulent air, maintains approximately straight-and-level flight if properly trimmed and left alone. It is designed to maintain a state of equilibrium in pitch, roll, and yaw. The pilot should be aware, however, that a change about one axis affects the stability of the others. The typical light airplane exhibits a good deal of stability in the yaw axis, slightly less in the pitch axis, and even lesser still in the roll axis. The key to emergency airplane attitude control, therefore, is to:

- Trim the airplane with the elevator trim so that it maintains hands-off level flight at cruise airspeed.

- Resist the tendency to over-control the airplane. Fly the attitude indicator with fingertip control. No attitude changes should be made unless the flight instruments indicate a definite need for a change.

- Make all attitude changes smooth and small, yet with positive pressure. Remember that a small change as indicated on the horizon bar corresponds to a proportionately much larger change in actual airplane attitude.

- Make use of any available aid in attitude control, such as autopilot or wing leveler.

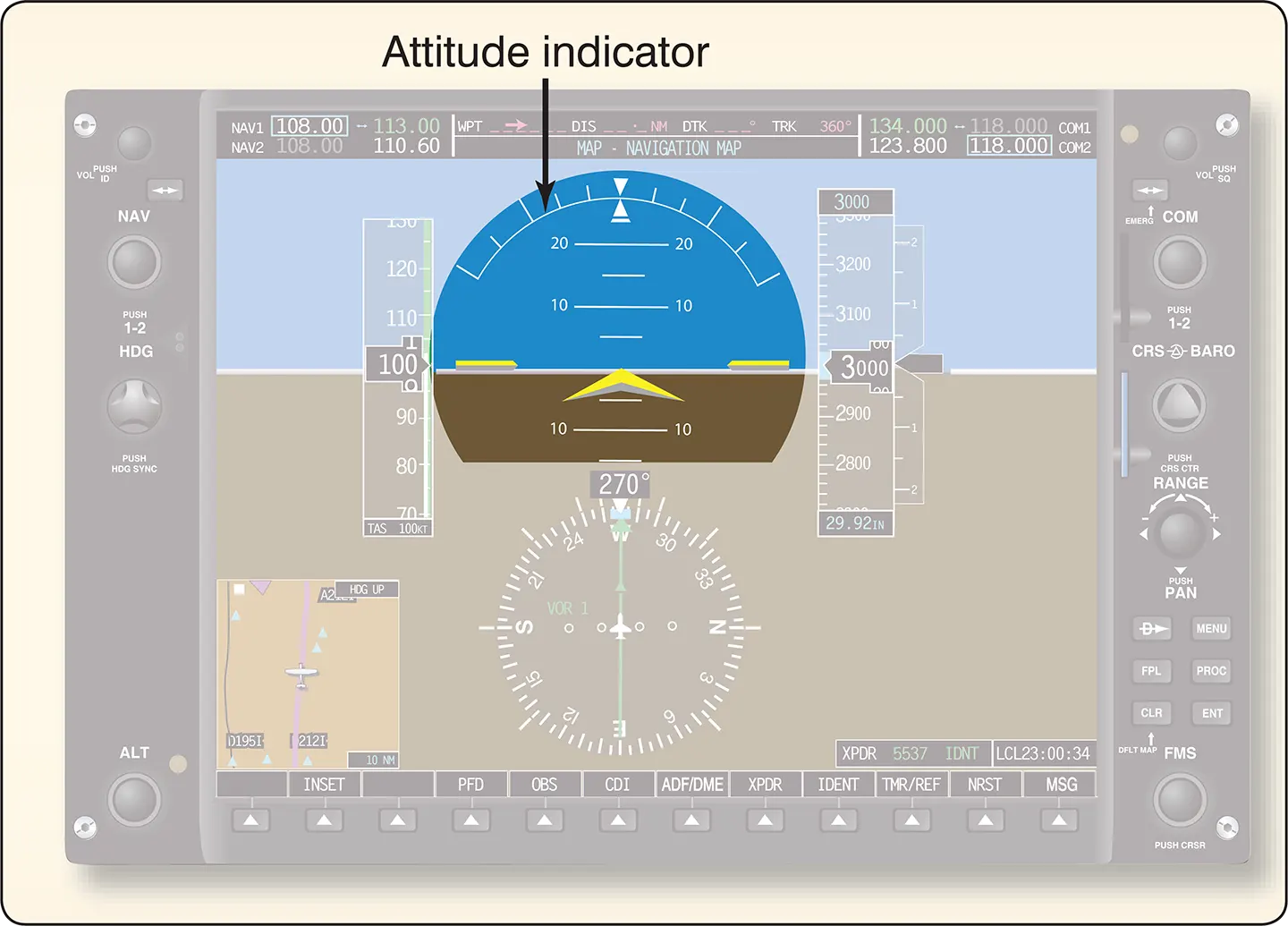

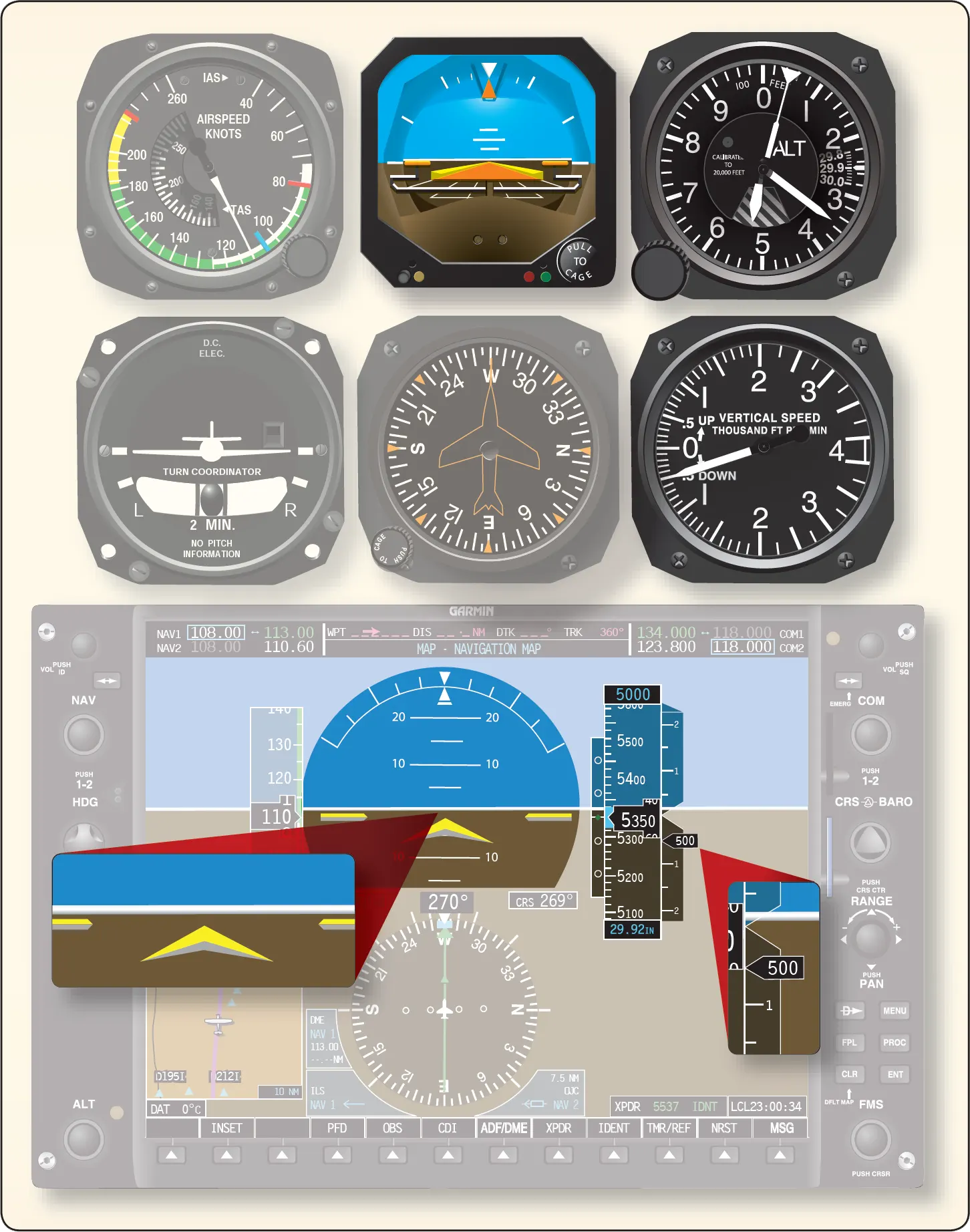

The primary instrument for attitude control is the attitude indicator. [Figure 1] Once the airplane is trimmed so that it maintains hands-off level flight at cruise airspeed, that airspeed need not vary until the airplane is slowed for landing. All turns, climbs, and descents can and should be made at this airspeed. Straight flight is maintained by keeping the wings level using “fingertip pressure” on the control wheel. Any pitch attitude change should be made by using no more than one bar width up or down.

Turns

Turns are perhaps the most potentially dangerous maneuver for the untrained instrument pilot for two reasons:

- The normal tendency of the pilot to over-control, leading to steep banks and the possibility of a “graveyard spiral.”

- The inability of the pilot to cope with the instability resulting from the turn.

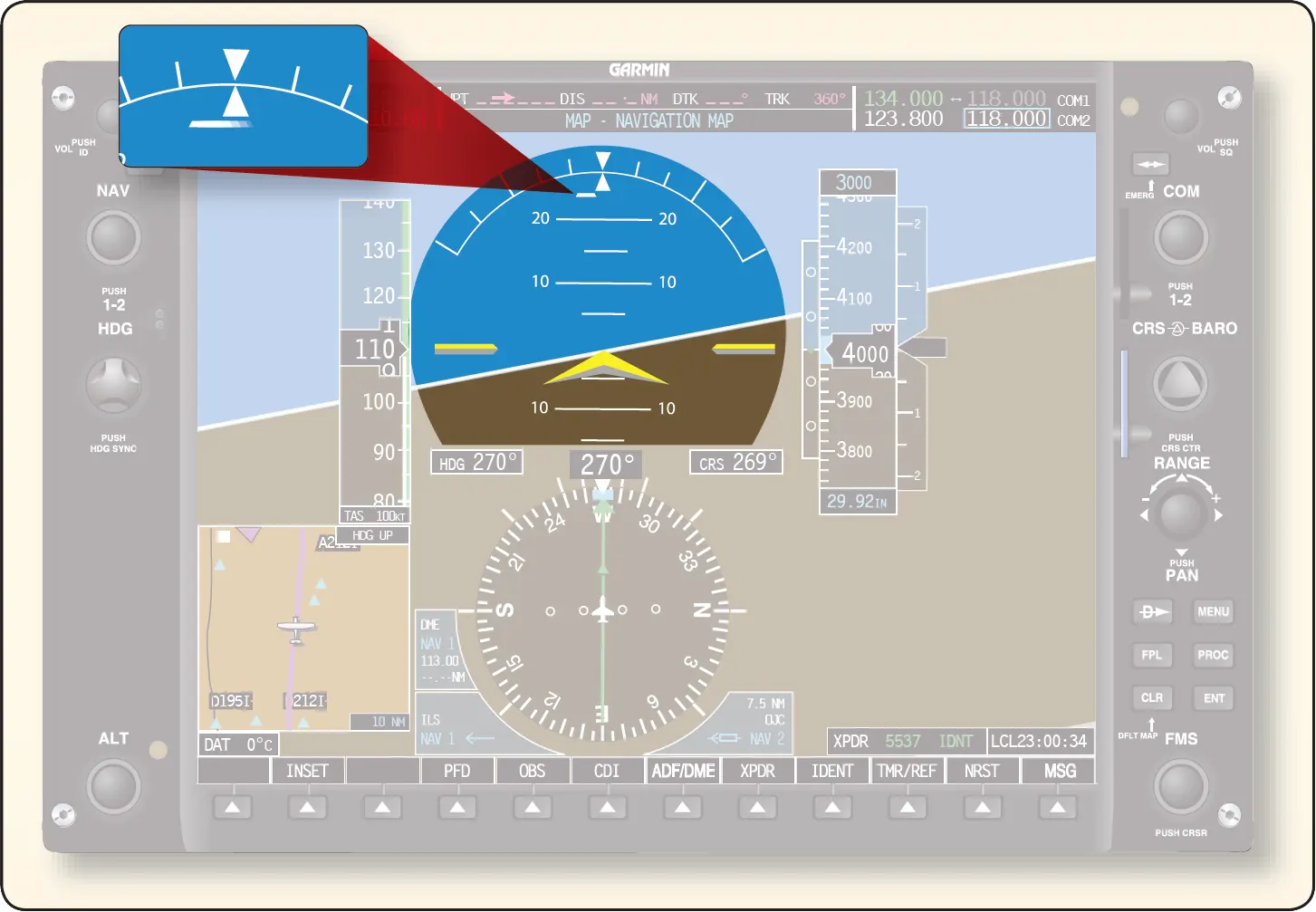

When a turn is to be made, the pilot should anticipate and cope with the relative instability of the roll axis. The smallest practical bank angle should be used—in any case no more than 10° bank angle. [Figure 2] A shallow bank takes very little vertical lift from the wings resulting in little if any deviation in altitude. It may be helpful to turn a few degrees and then return to level flight if a large change in heading is necessary. Repeat the process until the desired heading is reached. This process may relieve the progressive overbanking that often results from prolonged turns.

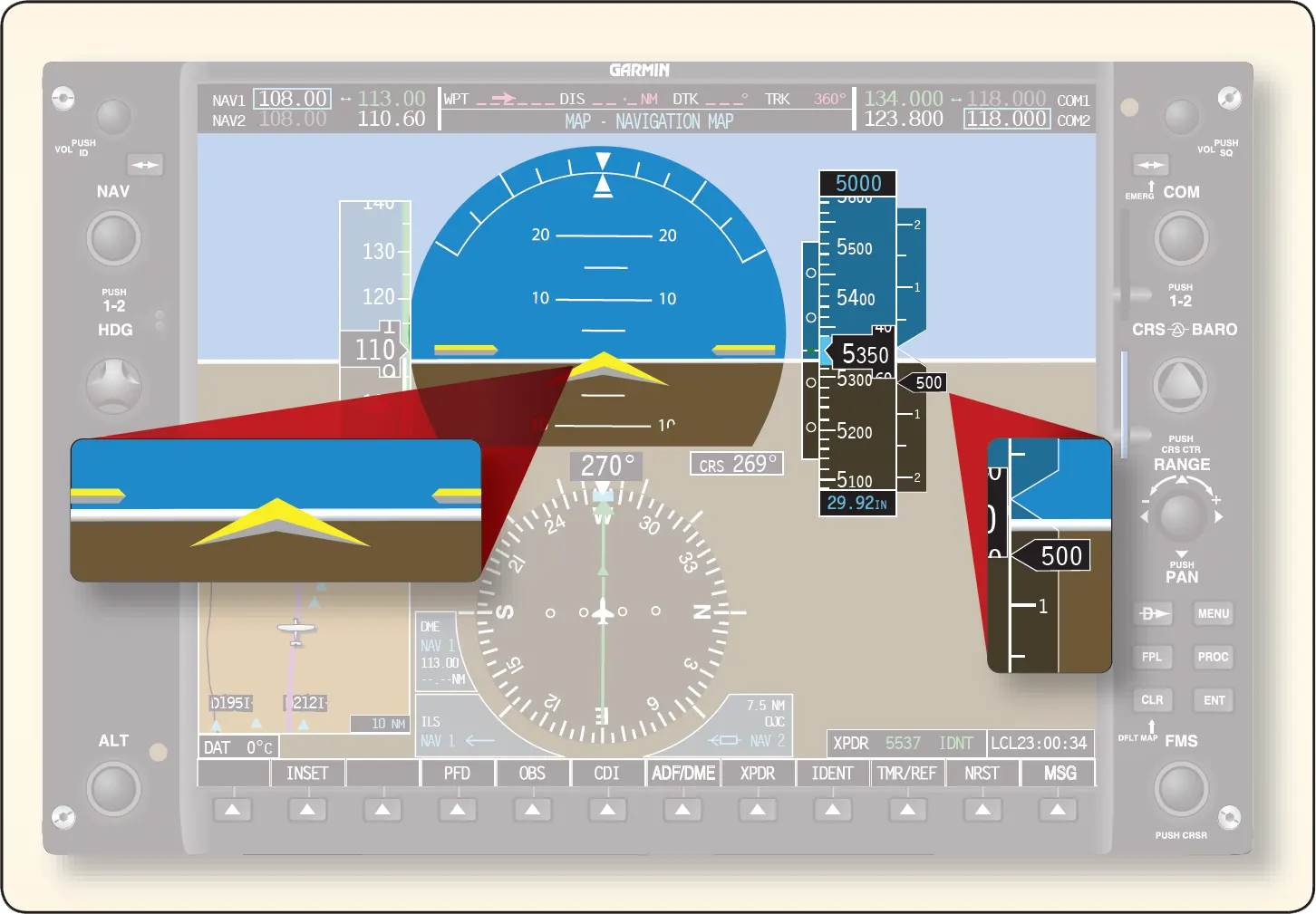

Climbs

If a climb is necessary, the pilot should raise the miniature airplane on the attitude indicator no more than one bar width and apply power. [Figure 3] The pilot should not attempt to attain a specific climb speed but accept whatever speed results. The objective is to deviate as little as possible from level flight attitude in order to disturb the airplane’s equilibrium as little as possible. If the airplane is properly trimmed, it assumes a nose-up attitude on its own commensurate with the amount of power applied. Torque and P-factor cause the airplane to have a tendency to bank and turn to the left. This should be anticipated and compensated for. If the initial power application results in an inadequate rate of climb, power should be increased in increments of 100 rpm or 1 inch of manifold pressure until the desired rate of climb is attained. Maximum available power is seldom necessary. The more power that is used, the more the airplane wants to bank and turn to the left. Resuming level flight is accomplished by first decreasing pitch attitude to level on the attitude indicator using slow but deliberate pressure, allowing airspeed to increase to near cruise value and then decreasing power.

Descents

Descents are very much the opposite of the climb procedure if the airplane is properly trimmed for hands-off straight-and-level flight. In this configuration, the airplane requires a certain amount of thrust to maintain altitude. The pitch attitude is controlling the airspeed. The engine power, therefore, (translated into thrust by the propeller) is maintaining the selected altitude. Following a power reduction, however slight, there is an almost imperceptible decrease in airspeed. However, even a slight change in speed results in less down load on the tail, whereupon the designed nose heaviness of the airplane causes it to pitch down just enough to maintain the airspeed for which it was trimmed. The airplane then descends at a rate directly proportionate to the amount of thrust that has been removed. Power reductions should be made in increments of 100 rpm or 1 inch of manifold pressure and the resulting rate of descent should never exceed 500 fpm. The wings should be held level on the attitude indicator, and the pitch attitude should not exceed one bar width below level. [Figure 4]

Combined Maneuvers

Combined maneuvers, such as climbing or descending turns, should be avoided if at all possible by an untrained instrument pilot. Combining maneuvers only compounds the problems encountered in individual maneuvers and increases the risk of control loss. The objective is to keep the airplane under control by maintaining as much of the airplane’s natural equilibrium as possible. Deviating as little as possible from straight-and-level flight attitude makes this much easier.

When being assisted by ATC, the pilot may detect a sense of urgency while being directed to change heading and/or altitude. This sense of urgency reflects a normal concern for safety on the part of the controller. Nevertheless, the pilot should not let this prompting lead to rushing into a maneuver that could result in loss of control. It’s reasonable to ask the controller to slow down, if this becomes an issue.

Transition to Visual Flight

One of the most difficult tasks a trained and qualified instrument pilot contends with is the transition from instrument to visual flight prior to landing. For the untrained instrument pilot, these difficulties are magnified.

The difficulties center around acclimatization and orientation. On an instrument approach, the trained instrument pilot prepares in advance for the transition to visual flight. The pilot has a mental picture of what to expect when the transition to visual flight is made and will quickly acclimate to the new environment. Geographical orientation also begins before the transition, as the pilot visualizes where the airplane is in relation to the airport/runway.

In an ideal situation, the transition to visual flight is made with ample time, at a sufficient altitude above terrain, and to visibility conditions sufficient to accommodate acclimatization and geographical orientation. This, however, is not always the case. The untrained instrument pilot may find the visibility still limited, the terrain completely unfamiliar, and altitude above terrain such that a “normal” airport traffic pattern and landing approach is not possible. Additionally, the pilot is most likely under considerable self-induced psychological pressure to get the airplane on the ground. The pilot should take this into account and, if possible, allow time to become acclimatized and geographically oriented before attempting an approach and landing, even if it means flying straight and level for a time or circling the airport. This is especially true at night.