Maximum Acceptable Descent Rates

Operational experience and research have shown that a descent rate of greater than approximately 1,000 fpm is unacceptable during the final stages of an approach (below 1,000 feet AGL). This is due to a human perceptual limitation that is independent of the type of airplane or helicopter. Therefore, the operational practices and techniques must ensure that descent rates greater than 1,000 fpm are not permitted in either the instrument or visual portions of an approach and landing operation.

For short runways, arriving at the MDA at the MAP when the MAP is located at the threshold may require a missed approach for some aircraft. For non-precision approaches, a descent rate should be used that ensures the aircraft reaches the MDA at a distance from the threshold that allows landing in the TDZ. On many IAPs, this distance is annotated by a VDP. If no VDP is annotated, calculate a normal descent point to the TDZ. To determine the required rate of descent, subtract the TDZE from the FAF altitude and divide this by the time inbound. For example, if the FAF altitude is 2,000 feet MSL, the TDZE is 400 feet MSL and the time inbound is two minutes, an 800 fpm rate of descent should be used.

To verify the aircraft is on an approximate three degree glidepath, use a calculation of 300 feet to 1 NM. The glidepath height above TDZE is calculated by multiplying the NM distance from the threshold by 300. For example, at 10 NM the aircraft should be 3,000 feet above the TDZE, at 5 NM the aircraft should be 1,500 feet above the TDZE, at 2 NM the aircraft should be 600 feet above the TDZE, and at 1.5 NM the aircraft should be 450 feet above the TDZE until a safe landing can be made. Using the example in the previous text, the aircraft should arrive at the MDA (800 feet MSL) approximately 1.3 NM from the threshold and in a position to land within the TDZ. Techniques for deriving a 300-to-1 glide path include using DME, distance advisories provided by radar-equipped control towers, RNAV, GPS, dead reckoning, and pilotage when familiar features on the approach course are visible. The runway threshold should be crossed at a nominal height of 50 feet above the TDZE.

Transition to a Visual Approach

The transition from instrument flight to visual flight during an instrument approach can be very challenging, especially during low visibility operations. Aircrews should use caution when transitioning to a visual approach at times of shallow fog. Adequate visibility may not exist to allow flaring of the aircraft. Aircrews must always be prepared to execute a missed approach/go-around. Additionally, single-pilot operations make the transition even more challenging. Approaches with vertical guidance add to the safety of the transition to visual because the approach is already stabilized upon visually acquiring the required references for the runway. 100 to 200 feet prior to reaching the DA, DH, or MDA, most of the PM’s attention should be outside of the aircraft in order to visually acquire at least one visual reference for the runway, as required by the regulations. The PF should stay focused on the instruments until the PM calls out any visual aids that can be seen, or states “runway in sight. ”The PF should then begin the transition to visual flight. It is common practice for the PM to call out the V/S during the transition to confirm to the PF that the instruments are being monitored, thus allowing more of the PF’s attention to be focused on the visual portion of the approach and landing. Any deviations from the stabilized approach criteria should also be announced by the PM.

Single-pilot operations can be much more challenging because the pilot must continue to fly by the instruments while attempting to acquire a visual reference for the runway. While it is important for both pilots of a two-pilot aircraft to divide their attention between the instruments and visual references, it is even more critical for the single- pilot operation. The flight visibility must also be at least the visibility minimum stated on the instrument approach chart, or as required by regulations. CAT II and III approaches have specific requirements that may differ from CAT I precision or non-precision approach requirements regarding transition to visual and landing. This information can be found in the operator’s OpSpecs or FOM.

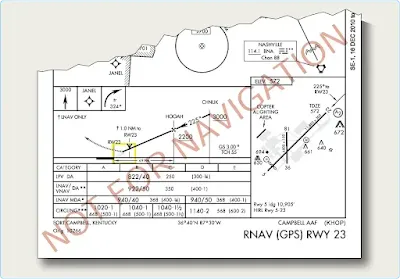

The visibility published on an approach chart is dependent on many variables, including the height above touchdown for straight-in approaches or height above airport elevation for circling approaches. Other factors include the approach light system coverage, and type of approach procedure, such as precision, non-precision, circling or straight-in. Another factor determining the minimum visibility is the penetration of the 34:1 and 20:1 surfaces. These surfaces are inclined planes that begin 200 feet out from the runway and extend outward to the DA point (for approaches with vertical guidance), the VDP location (for non-precision approaches) and 10,000 feet for an evaluation to a circling runway. If there is a penetration of the 34:1 surface, the published visibility can be no lower than three-fourths SM. If there is penetration of the 20:1 surface, the published visibility can be no lower than 1 SM with a note prohibiting approaches to the affected runway at night (both straight-in and circling). [Figure 1 ] Circling may be permitted at night if penetrating obstacles are marked and lighted. If the penetrating obstacles are not marked and lighted, a note is published that night circling is “Not Authorized.” Pilots should be aware of these penetrating obstacles when entering the visual and/or circling segments of an approach and take adequate precautions to avoid them. For RNAV approaches only, the presence of a grey shaded line from the MDA to the runway symbol in the profile view is an indication that the visual segment below the MDA is clear of obstructions on the 34:1 slope. Absence of the gray shaded area indicates the 34:1 OCS is not free of obstructions. [Figure 2]

|

| Figure 1. Determination of visibility minimums |

|

| Figure 2. RNAV approach Fort Campbell, Kentucky |

Missed Approach

Many reasons exist for executing a missed approach. The primary reasons, of course, are that the required flight visibility prescribed in the IAP being used does not exist when natural vision is used under 14 CFR Part 91, § 91.175c, the required enhanced flight visibility is less than that prescribed in the IAP when an EFVS is used under 14 CFR Part 91, § 91.176, or the required visual references for the runway cannot be seen upon arrival at the DA, DH, or MAP. In addition, according to 14 CFR Part 91, the aircraft must continuously be in a position from which a descent to a landing on the intended runway can be made at a normal rate of descent using normal maneuvers, and for operations conducted under Part 121 or 135, unless that descent rate allows touchdown to occur within the TDZ of the runway of intended landing. CAT II and III approaches call for different visibility requirements as prescribed by the FAA Administrator.

|

| Figure 3. Orlando Executive Airport, Orlando, Florida, ILS RWY 7 |

|

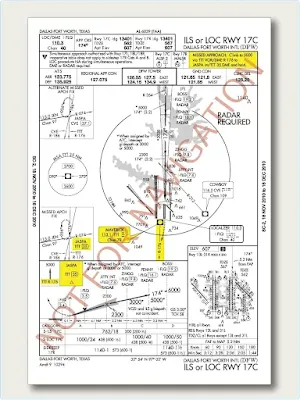

| Figure 4 Missed approach procedures for Dallas-Fort Worth International (DFW)4 |

|

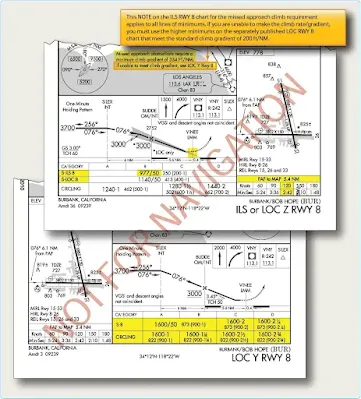

| Figure 5. Missed approach point depiction and steeper than standard climb gradient requirements |

|

| Figure 6. Two sets of minimums required when a climb gradient greater than 200 ft/NM is required |

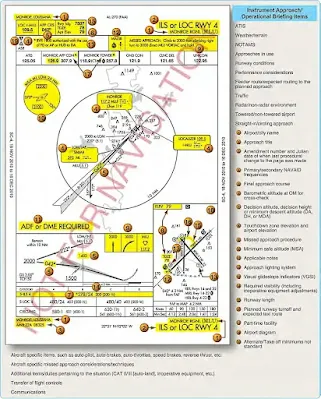

Example Approach Briefing

During an instrument approach briefing, the name of the airport and the specific approach procedure should be identified to allow other crewmembers the opportunity to cross-reference the chart being used for the brief. This ensures that pilots intending to conduct an instrument approach have collectively reviewed and verified the information pertinent to the approach. Figure 7 gives an example of the items to be briefed and their sequence. Although the following example is based on multi-crew aircraft, the process is also applicable to single-pilot operations. A complete instrument approach and operational briefing example follows.

|

| Figure 7. Example of approach chart briefing sequence |

Instrument Approach Procedure Segments

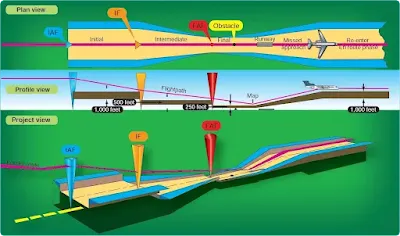

An instrument approach may be divided into as many as four approach segments: initial, intermediate, final, and missed approach. Additionally, feeder routes provide a transition from the en route structure to the IAF. FAA Order 8260.3 criteria provides obstacle clearance for each segment of an approach procedure as shown in Figure 8.

|

| Figure 8. Approach segments and obstacle clearance |

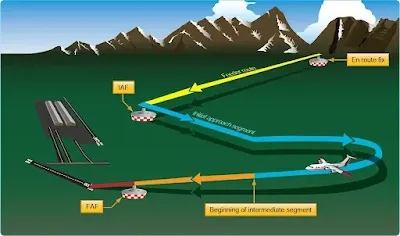

Feeder Routes

By definition, a feeder route is a route depicted on IAP charts to designate routes for aircraft to proceed from the en route structure to the IAF. [Figure 9 ] Feeder routes, also referred to as approach transitions, technically are not considered approach segments but are an integral part of many IAPs. Although an approach procedure may have several feeder routes, pilots normally choose the one closest to the en route arrival point. When the IAF is part of the en route structure, there may be no need to designate additional routes for aircraft to proceed to the IAF.

|

| Figure 9. Feeder routes |

Terminal Routes

In cases where the IAF is part of the en route structure and feeder routes are not required, a transition or terminal route is still needed for aircraft to proceed from the IAF to the intermediate fix (IF). These routes are initial approach segments because they begin at the IAF. Like feeder routes, they are depicted with course, minimum altitude, and distance to the IF. Essentially, these routes accomplish the same thing as feeder routes but they originate at an IAF, whereas feeder routes terminate at an IAF. [Figure 10 ]

|

| Figure 10. Terminal routes |

DME Arcs

DME arcs also provide transitions to the approach course, but DME arcs are actually approach segments while feeder routes, by definition, are not. When established on a DME arc, the aircraft has departed the en route phase and has begun the approach and is maneuvering to enter an intermediate or final segment of the approach. DME arcs may also be used as an intermediate or a final segment, although they are extremely rare as final approach segments.

|

| Figure 11. DME arc obstruction clearance |

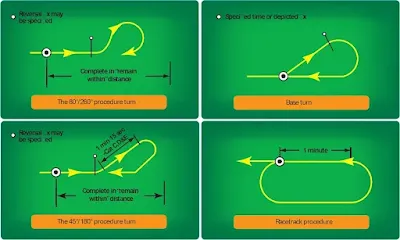

Course Reversal

Some approach procedures do not permit straight-in approaches unless pilots are being radar vectored. In these situations, pilots are required to complete a procedure turn (PT) or other course reversal, generally within 10 NM of the PT fix, to establish the aircraft inbound on the intermediate or final approach segment.

|

| Figure 12. Course reversal methods |

|

| Figure 13. Procedure turn obstacle clearance |

Initial Approach Segment

The purposes of the initial approach segment are to provide a method for aligning the aircraft with the intermediate or final approach segment and to permit descent during the alignment. This is accomplished by using a DME arc, a course reversal, such as a procedure turn or holding pattern, or by following a terminal route that intersects the final approach course. The initial approach segment begins at an IAF and usually ends where it joins the intermediate approach segment or at an IF. The letters IAF on an approach chart indicate the location of an IAF and more than one may be available. Course, distance, and minimum altitudes are also provided for initial approach segments. A given procedure may have several initial approach segments. When more than one exists, each joins a common intermediate segment, although not necessarily at the same location.

Many RNAV approaches make use of a dual-purpose IF/ IAF associated with a hold-in-lieu-of PT (HILO) anchored at the Intermediate Fix. The HILO forms the Initial Approach Segment when course reversal is required.

When the PT is required, it is only necessary to enter the holding pattern to reverse course. The dual purpose fix functions as an IAF in that case. Once the aircraft has entered the hold and is returning to the fix on the inbound course, the dual-purpose fix becomes an IF, marking the beginning of the intermediate segment.

ATC may provide a vector to an IF at an angle of 90 degrees or less and specify “Cleared Straight-in (type) Approach”. In those cases, the radar vector is providing the initial approach segment and the pilot should not fly the PT without a clearance from ATC.

Occasionally, a chart may depict an IAF, although there is no initial approach segment for the procedure. This usually occurs at a point located within the en route structure where the intermediate segment begins. In this situation, the IAF signals the beginning of the intermediate segment.

Intermediate Approach Segment

The intermediate segment is designed primarily to position the aircraft for the final descent to the airport. Like the feeder route and initial approach segment, the chart depiction of the intermediate segment provides course, distance, and minimum altitude information.

The intermediate segment, normally aligned within 30° of the final approach course, begins at the IF, or intermediate point, and ends at the beginning of the final approach segment. In some cases, an IF is not shown on an approach chart. In this situation, the intermediate segment begins at a point where you are proceeding inbound to the FAF, are properly aligned with the final approach course, and are located within the prescribed distance prior to the FAF. An instrument approach that incorporates a procedure turn is the most common example of an approach that may not have a charted IF. The intermediate segment in this example begins when you intercept the inbound course after completing the procedure turn. [Figure 14]

|

| Figure 14. Approach without a designated IF |

Final Approach Segment

The final approach segment for an approach with vertical guidance or a precision approach begins where the glideslope/glidepath intercepts the minimum glideslope/ glidepath intercept altitude shown on the approach chart. If ATC authorizes a lower intercept altitude, the final approach segment begins upon glideslope/glidepath interception at that altitude. For a non-precision approach, the final approach segment begins either at a designated FAF, which is depicted as a cross on the profile view, or at the point where the aircraft is established inbound on the final approach course. When a FAF is not designated, such as on an approach that incorporates an on-airport VOR or NDB, this point is typically where the procedure turn intersects the final approach course inbound. This point is referred to as the final approach point (FAP). The final approach segment ends at either the designated MAP or upon landing.

There are three types of procedures based on the final approach course guidance:

- Precision approach (PA)—an instrument approach based on a navigation system that provides course and glidepath deviation information meeting precision standards of ICAO Annex 10. For example, PAR, ILS, and GLS are precision approaches.

- Approach with vertical guidance (APV) —an instrument approach based on a navigation system that is not required to meet the precision approach standards of ICAO Annex 10, but provides course and glidepath deviation information. For example, Baro-VNAV, LDA with glidepath, LNAV/VNAV and LPV are APV approaches.

- Non-precision approach (NPA)—an instrument approach based on a navigation system that provides course deviation information but no glidepath deviation information. For example, VOR, TACAN, LNAV, NDB, LOC, and ASR approaches are examples of NPA procedures.

Missed Approach Segment

The missed approach segment begins at the MAP and ends at a point or fix where an initial or en route segment begins. The actual location of the MAP depends upon the type of approach you are flying. For example, during a precision or an APV approach, the MAP occurs at the DA or DH on the glideslope/glidepath. For non-precision approaches, the MAP is either a fix, NAVAID, or after a specified period of time has elapsed after crossing the FAF.

Approach Clearance

According to FAA Order 7110.65, ATC clearances authorizing instrument approaches are issued on the basis that if visual contact with the ground is made before the approach is completed, the entire approach procedure is followed unless the pilot receives approval for a contact approach, is cleared for a visual approach, or cancels the IFR flight plan.

Approach clearances are issued based on known traffic. The receipt of an approach clearance does not relieve the pilot of his or her responsibility to comply with applicable parts of the CFRs and notations on instrument approach charts, which impose on the pilot the responsibility to comply with or act on an instruction, such as “procedure not authorized at night.” The name of the approach, as published, is used to identify the approach. Approach name items within parentheses are not included in approach clearance phraseology.

Vectors To Final Approach Course

The approach gate is an imaginary point used within ATC as a basis for vectoring aircraft to the final approach course. The gate is established along the final approach course one mile from the FAF on the side away from the airport and is no closer than 5 NM from the landing threshold. Controllers are also required to ensure the assigned altitude conforms to the following:

- For a precision approach, at an altitude not above the glideslope/glidepath or below the minimum glideslope/glidepath intercept altitude specified on the approach procedure chart.

- For a non-precision approach, at an altitude that allows descent in accordance with the published procedure. Further, controllers must assign headings that intercept the final approach course no closer than the following table:

A typical vector to the final approach course and associated approach clearance is as follows:

“…four miles from LIMAA, turn right heading three four zero, maintain two thousand until established on the localizer, cleared ILS runway three six approach.”

Other clearance formats may be used to fit individual circumstances, but the controller should always assign an altitude to maintain until the aircraft is established on a segment of a published route or IAP. The altitude assigned must guarantee IFR obstruction clearance from the point at which the approach clearance is issued until the aircraft is established on a published route. 14 CFR Part 91, § 91.175 (j) prohibits a pilot from making a procedure turn when vectored to a FAF or course, when conducting a timed approach, or when the procedure specifies “NO PT.”

When vectoring aircraft to the final approach course, controllers are required to ensure the intercept is at least 2 NM outside the approach gate. Exceptions include the following situations, but do not apply to RNAV aircraft being vectored for a GPS or RNAV approach:

- When the reported ceiling is at least 500 feet above the MVA/MIA and the visibility is at least 3 SM (maybe a pilot report (PIREP) if no weather is reported for the airport), aircraft may be vectored to intercept the final approach course closer than 2 NM outside the approach gate but no closer than the approach gate.

- If specifically requested by the pilot, aircraft maybe vectored to intercept the final approach course inside the approach gate but no closer than the FAF.

Nonradar Environment

In the absence of radar vectors, an instrument approach begins at an IAF. An aircraft that has been cleared to a holding fix that, prior to reaching that fix, is issued a clearance for an approach, but not issued a revised routing, such as, “proceed direct to…” is expected to proceed via the last assigned route, a feeder route if one is published on the approach chart, and then to commence the approach as published. If, by following the route of flight to the holding fix, the aircraft would overfly an IAF or the fix associated with the beginning of a feeder route to be used, the aircraft is expected to commence the approach using the published feeder route to the IAF or from the IAF as appropriate. The aircraft would not be expected to overfly and return to the IAF or feeder route.