Airport traffic patterns ensure that air traffic moves into and out of an airport safely. The direction and placement of the pattern, the altitude at which it is to be flown, and the procedures for entering and exiting the pattern may depend on local conditions. Information regarding the procedures for a specific airport can be found in the Chart Supplements. General information on airport operations and traffic patterns can also be found in the Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM).

https://aircraftsystemstech.com/humix/video/UIWeIoRjlIfAirport Traffic Patterns and Operations

Just as roads and streets are essential for operating automobiles, airports or airstrips are essential for operating airplanes. Since flight begins and ends at an airport or other suitable landing field, pilots need to learn the traffic rules, traffic procedures, and traffic pattern layouts in use at various airports.

When an automobile is driven on congested city streets, it can be brought to a stop to give way to conflicting traffic. Airplane pilots do not have that option. Consequently, traffic patterns and traffic control procedures exist to minimize conflicts during takeoffs, departures, arrivals, and landings. The exact nature of each airport traffic pattern is dependent on the runway in use, wind conditions (which determine the runway in use), obstructions, and other factors.

Airports vary in complexity from small grass or sod strips to major terminals with paved runways and taxiways. Regardless of the type of airport, a pilot should know and abide by the applicable rules and operating procedures. In addition to checking the traffic pattern and operating procedures for airports of intended use in the Chart Supplements, pilots should know how to interpret any airport visual markings and signs that may be encountered. In total, the information provided to the pilot keeps air traffic moving with maximum safety and efficiency. However, the use of any traffic pattern, service, or procedure does not diminish the pilot’s responsibility to see and avoid other aircraft from ramp-out to ramp-in.

When operating at an airport with an operating control tower, the pilot receives a clearance to approach or depart, as well as pertinent information about the traffic pattern by radio. The tower operator can instruct pilots to enter the traffic pattern at any point or to make a straight-in approach without flying the usual rectangular pattern. Many other deviations are possible if the tower operator and the pilot work together in an effort to keep traffic moving smoothly. Jets or heavy airplanes will frequently fly wider and/or higher patterns than lighter airplanes, and will sometimes make a straight-in approach for landing.

A pilot is not expected to have extensive knowledge of all traffic patterns at all airports, but if the pilot is familiar with the basic rectangular pattern, it is easy to make proper approaches and departures from most airports, regardless of whether or not they have control towers.

However, if there is not a control tower, it is the pilot’s responsibility to determine the direction of the traffic pattern, to comply with appropriate traffic rules, and to display common courtesy toward other pilots operating in the area. When operating at airports without a control tower, the pilot may not see all traffic. Therefore, the pilot should develop the habit of continued scanning even when air traffic appears light or nil. Adherence to the basic rectangular traffic pattern reduces the possibility of conflicts and reduces the probability of a midair collision.

Standard Airport Traffic Patterns

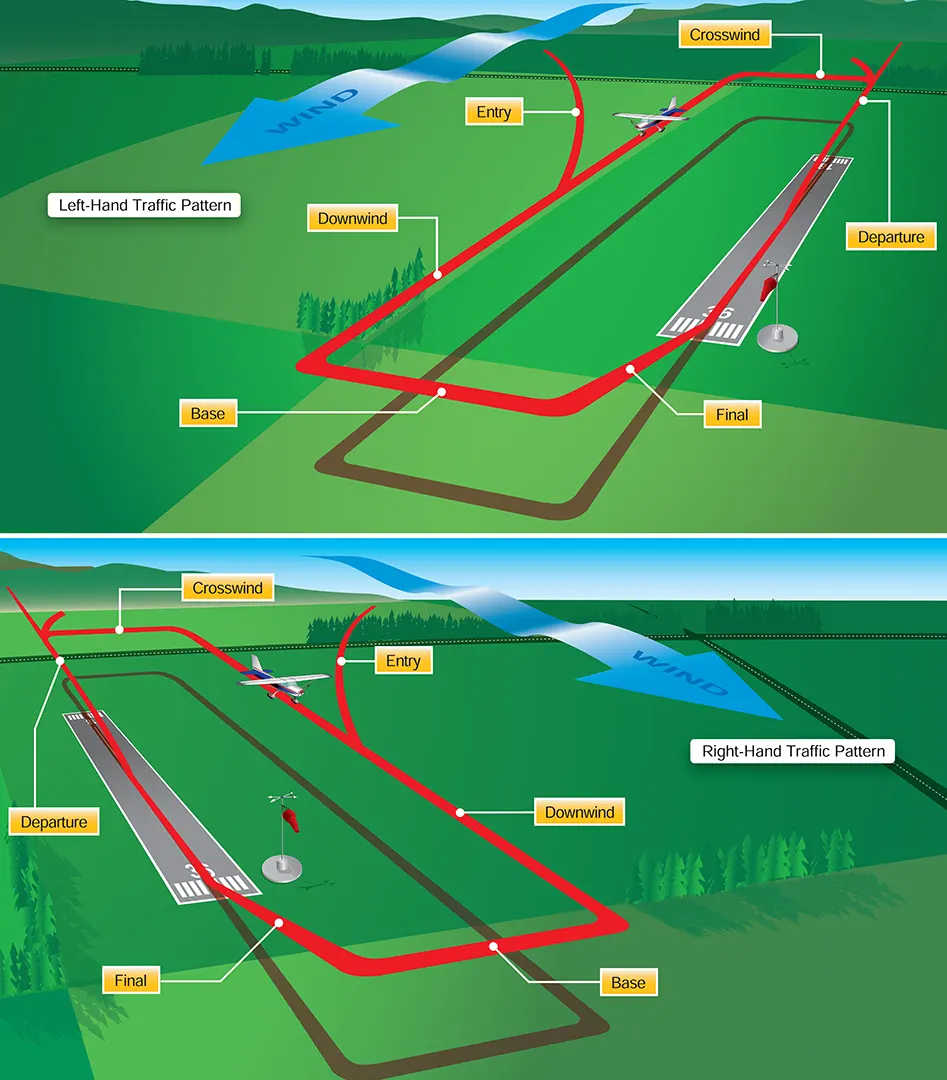

An airport traffic pattern includes the direction and altitude of the pattern and procedures for entering and leaving the pattern. Unless the airport displays approved visual markings indicating that turns should be made to the right, the pilot should make all turns in the pattern to the left.

Figure 1 shows a standard rectangular traffic pattern. The traffic pattern altitude is usually 1,000 feet above the elevation of the airport surface. The use of a common altitude at a given airport is the key factor in minimizing the risk of collisions at airports without operating control towers.

Aircraft speeds are restrained by 14 CFR part 91, section 91.117. When operating in the traffic pattern at most airports with an operating control tower, aircraft typically fly at airspeeds no greater than 200 knots (230 miles per hour (mph)). Sensible practice suggests flying at or below these speeds when operating in the traffic pattern of an airport without an operating control tower. In any case, the pilot should adjust the airspeed, when necessary, so that it is compatible with the airspeed of other aircraft in the traffic pattern.

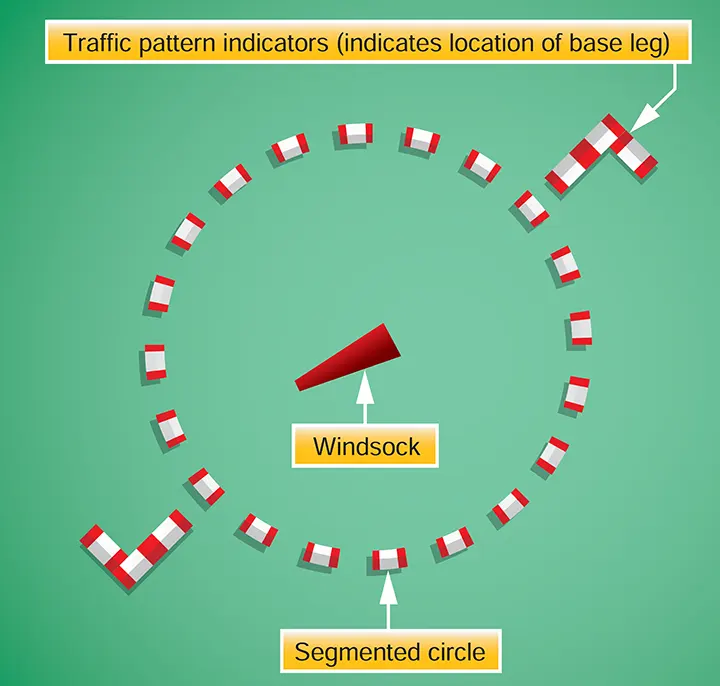

When entering the traffic pattern at an airport without an operating control tower, inbound pilots are expected to observe other aircraft already in the pattern and to conform to the traffic pattern in use. The pilot should enter the traffic pattern at a point well clear of any other observed aircraft. If there are no other aircraft observed, the pilot should check traffic indicators and wind indicators on the ground to determine which runway and traffic pattern direction to use. [Figure 2] Many airports have L-shaped traffic pattern indicators displayed with a segmented circle adjacent to the runway. The short member of the L shows the direction in which traffic pattern turns are made when using the runway parallel to the long member. The pilot should check the indicators from a distance or altitude well above the traffic pattern in case any other aircraft are in the traffic pattern.

Consider the following points when arriving at an airport for landing:

- The pilot should be aware of the appropriate traffic pattern altitude before entering the pattern and remain clear of the traffic flow until established on the entry leg.

- The traffic pattern is normally entered at a 45° angle to the downwind leg, headed toward a point abeam the midpoint of the runway to be used for landing.

- The pilot should ensure that the entry leg is of sufficient length to provide a clear view of the entire traffic pattern and to allow adequate time for planning the intended path in the pattern and the landing approach.

- Entries into traffic patterns while descending create specific collision hazards and should be avoided.

The downwind leg is a course flown parallel to the landing runway, but in a direction opposite to the intended landing direction. This leg is flown approximately 1/2 to 1 mile out from the landing runway and at the specified traffic pattern altitude. When flying on the downwind leg, the pilot should complete all before-landing checks and extend the landing gear if the airplane is equipped with retractable landing gear. Pattern altitude is maintained until at least abeam the approach end of the landing runway. At this point, the pilot should reduce power and begin a descent. The pilot should continue the downwind leg past a point abeam the approach end of the runway to a point approximately 45° from the approach end of the runway, and make a medium-bank turn onto the base leg. Pilots should consider tailwinds and not descend too much on the downwind in order to have sufficient altitude to continue the descent on the base leg.

The base leg is the transitional part of the traffic pattern between the downwind leg and the final approach leg. Depending on the wind condition, the pilot should establish the base leg at a sufficient distance from the approach end of the landing runway to permit a gradual descent to the intended touchdown point. While on the base leg, the ground track of the airplane is perpendicular to the extended centerline of the landing runway, although the longitudinal axis of the airplane may not be aligned with the ground track if turned into the wind to counteract drift.

While on the base leg and before turning onto the final approach, the pilot should ensure that there is no close proximity to another aircraft already established on final approach. When two or more aircraft are approaching an airport for the purpose of landing, the aircraft at the lower altitude has the right-of-way. However, pilots should not take advantage of this rule to cut in front of another aircraft that is on final approach to land or to overtake that aircraft. If the turn to final would create a collision hazard, a go-around or avoidance maneuver is in order. A pilot trying to overtake another aircraft might be tempted to make an overly steep turn to final. If rushing the turn to increase the distance from another aircraft, there is good reason to abandon the approach and go around.

The final approach leg is a descending flightpath starting from the completion of the base-to-final turn and extending to the point of touchdown. This is probably the most important leg of the entire pattern, because of the sound judgment and precision needed to accurately control the airspeed and descent angle while approaching the intended touchdown point.

The pilot on final approach focuses on making a safe approach. If there is traffic on the runway, there should be sufficient time for that traffic to clear. If it appears that there may be a conflict, an early go-around may be in order. A pilot may go around and inform the controller. This is also a good time to verify the correct landing surface and avoid lining up with the wrong runway, an airport road, or a taxiway.

The upwind leg is a course flown parallel to the landing runway in the same direction as landing traffic. The upwind leg is flown at controlled airports and after go-arounds. When necessary, the upwind leg is the part of the traffic pattern in which the pilot will transition from the final approach to the climb altitude to initiate a go-around. When a safe altitude is attained, the pilot should commence a shallow-bank turn to the upwind side of the airport. This allows better visibility of the runway for departing aircraft.

The departure leg of the rectangular pattern is a straight course aligned with, and leading from, the takeoff runway. This leg begins at the point the airplane leaves the ground and continues until the pilot begins the 90° turn onto the crosswind leg.

On the departure leg after takeoff, the pilot should continue climbing straight ahead and, if remaining in the traffic pattern, commence a turn to the crosswind leg beyond the departure end of the runway within 300 feet of the traffic pattern altitude. If departing the traffic pattern, the pilot should continue straight out or exit with a 45° turn (to the left when in a left-hand traffic pattern or to the right when in a right-hand traffic pattern) beyond the departure end of the runway after reaching the traffic pattern altitude.

The crosswind leg is the part of the rectangular pattern that is horizontally perpendicular to the extended centerline of the takeoff runway. The pilot should enter the crosswind leg by making approximately a 90° turn from the upwind leg. The pilot should continue on the crosswind leg, to the downwind leg position.

If the takeoff is made into the wind, the wind will now be approximately perpendicular to the airplane’s flightpath. As a result, the pilot should turn or head the airplane slightly into the wind while on the crosswind leg to maintain a ground track that is perpendicular to the runway centerline extension.

Non-Towered Airports

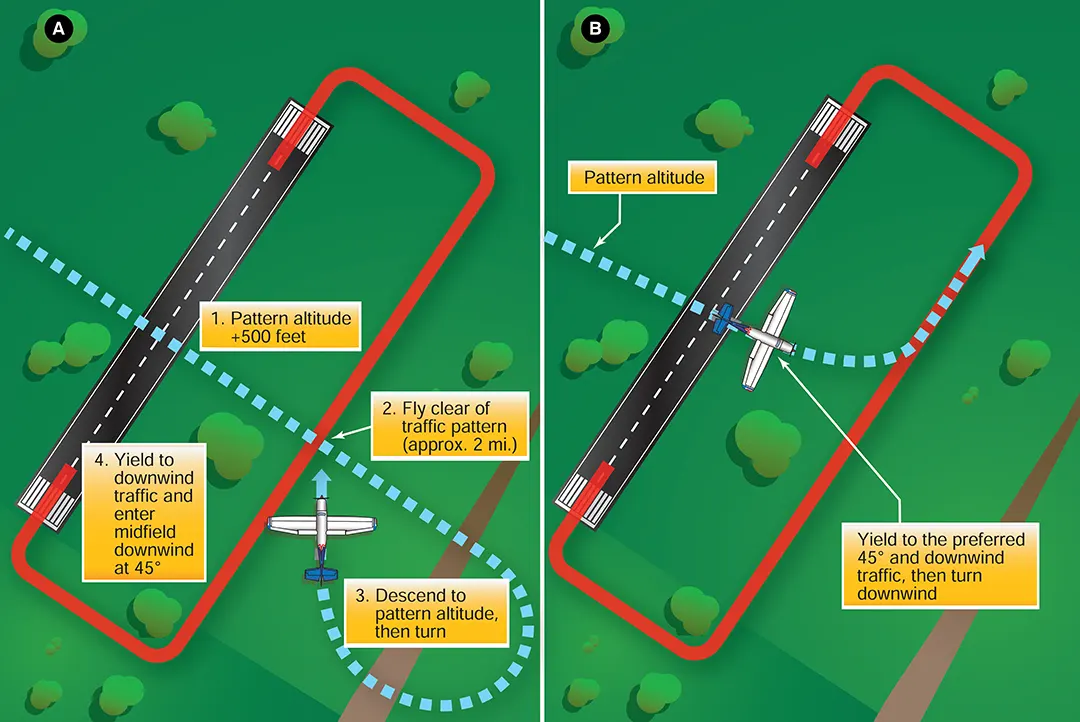

Non-towered airports traffic patterns are always entered at pattern altitude. How a pilot enters the pattern depends upon the direction of arrival. The preferred method for entering from the downwind leg side of the pattern is to approach the pattern on a course 45° to the downwind leg and join the pattern at midfield.

There are several ways to enter the pattern if the arrival occurs on the upwind leg side of the airport. One method of entry from the opposite side of the pattern is to announce intentions and cross over midfield at least 500 feet above pattern altitude (normally 1,500 feet AGL). However, if large or turbine aircraft operate at the airport, it is best to remain 2,000 feet AGL so as not to conflict with their traffic pattern. When well clear of the pattern—approximately 2 miles—the pilot should scan carefully for traffic, descend to pattern altitude, then turn right to enter at 45° to the downwind leg at midfield. [Figure 3A] An alternate method is to enter on a midfield crosswind at pattern altitude, carefully scan for traffic, announce intentions, and then turn downwind. [Figure 3B] This technique should not be used if the pattern is busy.

In either case, it is vital to announce intentions and to scan outside. Make course and speed adjustments that will lead to a successful pattern entry and give way to other aircraft on the preferred 45° entry or to aircraft already established on downwind.

Why is it advantageous to use the preferred 45° entry? If it is not possible to enter the pattern due to conflicting traffic, the pilot on a 45° entry can continue to turn away from the downwind, fly a safe distance away, and return for another attempt to join on the 45° entry—all while scanning for traffic.

Before joining the downwind leg, adjust course or speed to fit the traffic. Once fitting into the flow of traffic, adjust power on the downwind leg to avoid flying too fast or too slow. Speeds recommended by the airplane manufacturer should be used. They will generally fall between 70 to 90 knots for typical piston single-engine airplanes.

Safety Considerations

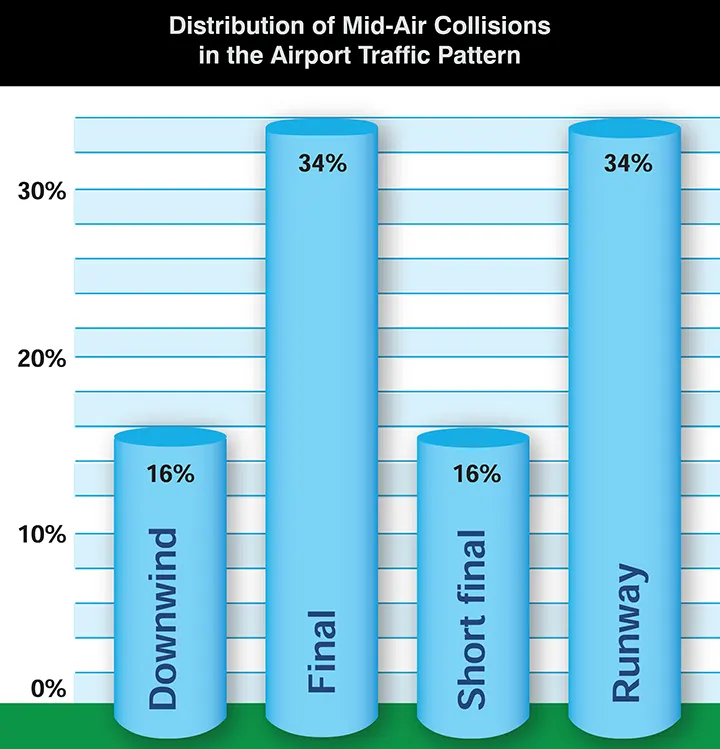

According to the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), the most probable cause of mid-air collisions is the pilot failing to see and avoid other aircraft. When near an airport, pilots should continue to scan for other aircraft and check blind spots caused by fixed aircraft structures, such as doorposts and wings. High-wing airplanes have restricted visibility above while low-wing airplanes have limited visibility below. The worst-case scenario is a low-wing airplane flying above a high-wing airplane. Banking from time to time can uncover blind spots. The pilot should also occasionally look to the rear of the airplane to check for other aircraft. Figure 4 depicts the greatest threat area for mid-air collisions in the traffic pattern.

Listed below are important facts regarding mid-air collisions:

- Mid-air collisions generally occur during daylight hours—56 percent occur in the afternoon, 32 percent occur in the morning, and 2 percent occur at night, dusk, or dawn.

- Most mid-air collisions occur under good visibility.

- A mid-air collision is most likely to occur between two aircraft going in the same direction.

- The majority of pilots involved in mid-air collisions are not on a flight plan.

- Nearly all accidents occur at or near uncontrolled airports and at altitudes below 1,000 feet.

- Pilots of all experience levels can be involved in mid-air collisions.

The following are some important procedures that all pilots should follow when flying in a traffic pattern or in the vicinity of an airport.

- Tune and verify radio frequencies before entering the airport traffic area.

- Monitor the correct Common Traffic Advisory Frequency (CTAF).

- Report position 10 miles out and listen for reports from other inbound traffic.

- At a non-towered airport, report entering downwind, turning downwind to base, and base to final.

- Descend to traffic pattern altitude before entering the pattern.

- Maintain a constant visual scan for other aircraft.

- Be aware that there may be aircraft in the pattern without radios.

- Use exterior lights to improve the chances of being seen.

The volume of traffic at an airport can create a hazardous environment. Airport traffic patterns are procedures that improve the flow of traffic at an airport and enhance safety when properly executed. Most reported mid-air collisions occur during the final or short-final approach leg of the airport traffic pattern.