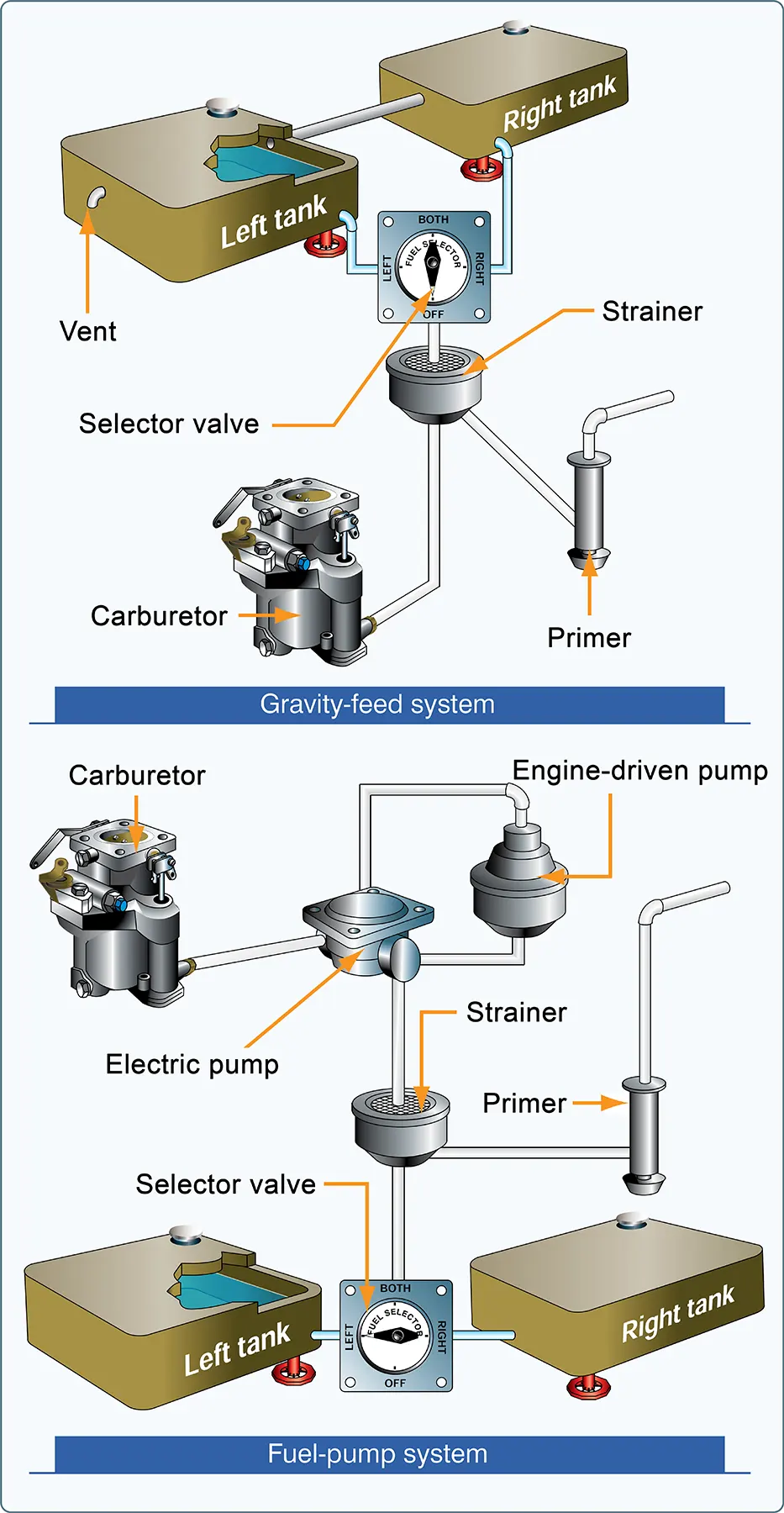

The fuel system is designed to provide an uninterrupted flow of clean fuel from the fuel tanks to the engine. The fuel must be available to the engine under all conditions of engine power, altitude, attitude, and during all approved flight maneuvers. Two common classifications apply to fuel systems in small aircraft: gravity-feed and fuel-pump systems.

https://aircraftsystemstech.com/humix/video/UIWeIoRjlIf

Gravity-Feed System

The gravity-feed system utilizes the force of gravity to transfer the fuel from the tanks to the engine. For example, on high-wing airplanes, the fuel tanks are installed in the wings. This places the fuel tanks above the carburetor, and the fuel is gravity fed through the system and into the carburetor. If the design of the aircraft is such that gravity cannot be used to transfer fuel, fuel pumps are installed. For example, on low-wing airplanes, the fuel tanks in the wings are located below the carburetor. [Figure 1]

Fuel-Pump System

Aircraft with fuel-pump systems have two fuel pumps. The main pump system is engine driven with an electrically-driven auxiliary pump provided for use in engine starting and in the event the engine pump fails. The auxiliary pump, also known as a boost pump, provides added reliability to the fuel system. The electrically-driven auxiliary pump is controlled by a switch in the flight deck.

Fuel Primer

Both gravity-feed and fuel-pump systems may incorporate a fuel primer into the system. The fuel primer is used to draw fuel from the tanks to vaporize fuel directly into the cylinders prior to starting the engine. During cold weather, when engines are difficult to start, the fuel primer helps because there is not enough heat available to vaporize the fuel in the carburetor. It is important to lock the primer in place when it is not in use. If the knob is free to move, it may vibrate out of position during flight which may cause an excessively rich fuel-air mixture. To avoid overpriming, read the priming instructions for the aircraft.

Fuel Tanks

The fuel tanks, normally located inside the wings of an airplane, have a filler opening on top of the wing through which they can be filled. A filler cap covers this opening.

The tanks are vented to the outside to maintain atmospheric pressure inside the tank. They may be vented through the filler cap or through a tube extending through the surface of the wing. Fuel tanks also include an overflow drain that may stand alone or be collocated with the fuel tank vent. This allows fuel to expand with increases in temperature without damage to the tank itself. If the tanks have been filled on a hot day, it is not unusual to see fuel coming from the overflow drain.

Fuel Gauges

The fuel quantity gauges indicate the amount of fuel measured by a sensing unit in each fuel tank and is displayed in gallons or pounds. Aircraft certification rules require accuracy in fuel gauges only when they read “empty.” Any reading other than “empty” should be verified. Do not depend solely on the accuracy of the fuel quantity gauges. Always visually check the fuel level in each tank during the preflight inspection, and then compare it with the corresponding fuel quantity indication.

If a fuel pump is installed in the fuel system, a fuel pressure gauge is also included. This gauge indicates the pressure in the fuel lines. The normal operating pressure can be found in the AFM/POH or on the gauge by color coding.

Fuel Selectors

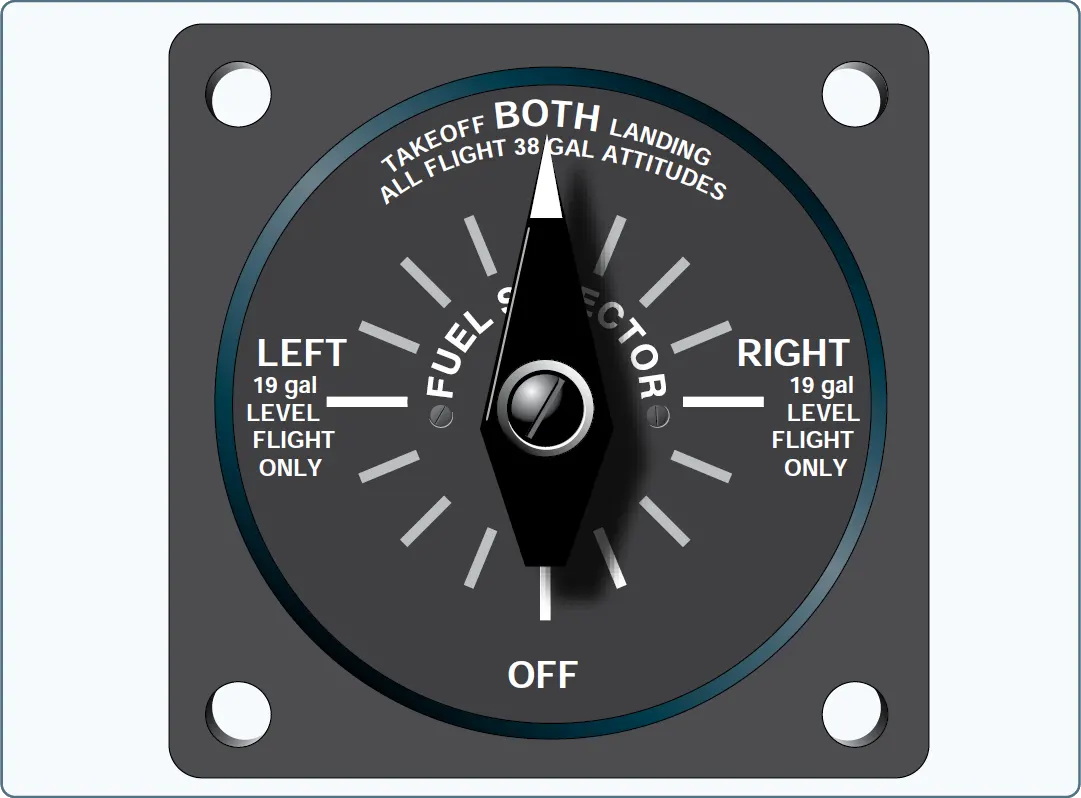

The fuel selector valve allows selection of fuel from various tanks. A common type of selector valve contains four positions: LEFT, RIGHT, BOTH, and OFF. Selecting the LEFT or RIGHT position allows fuel to feed only from the respective tank, while selecting the BOTH position feeds fuel from both tanks. The LEFT or RIGHT position may be used to balance the amount of fuel remaining in each wing tank. [Figure 2]

Fuel placards show any limitations on fuel tank usage, such as “level flight only” and/or “both” for landings and takeoffs.

Regardless of the type of fuel selector in use, fuel consumption should be monitored closely to ensure that a tank does not run completely out of fuel. Running a fuel tank dry does not only cause the engine to stop, but running for prolonged periods on one tank causes an unbalanced fuel load between tanks. Running a tank completely dry may allow air to enter the fuel system and cause vapor lock, which makes it difficult to restart the engine. On fuel-injected engines, the fuel becomes so hot it vaporizes in the fuel line, not allowing fuel to reach the cylinders.

Fuel Strainers, Sumps, and Drains

After leaving the fuel tank and before it enters the carburetor, the fuel passes through a strainer that removes any moisture and other sediments in the system. Since these contaminants are heavier than aviation fuel, they settle in a sump at the bottom of the strainer assembly. A sump is a low point in a fuel system and/or fuel tank. The fuel system may contain a sump, a fuel strainer, and fuel tank drains, which may be collocated.

The fuel strainer should be drained before each flight. Fuel samples should be drained and checked visually for water and contaminants.

Water in the sump is hazardous because in cold weather the water can freeze and block fuel lines. In warm weather, it can flow into the carburetor and stop the engine. If water is present in the sump, more water in the fuel tanks is probable, and they should be drained until there is no evidence of water. Never take off until all water and contaminants have been removed from the engine fuel system.

Because of the variation in fuel systems, become thoroughly familiar with the systems that apply to the aircraft being flown. Consult the AFM/POH for specific operating procedures.

Fuel Grades

Aviation gasoline (AVGAS) is identified by an octane or performance number (grade), which designates the antiknock value or knock resistance of the fuel mixture in the engine cylinder. The higher the grade of gasoline, the more pressure the fuel can withstand without detonating. Lower grades of fuel are used in lower-compression engines because these fuels ignite at a lower temperature. Higher grades are used in higher-compression engines because they ignite at higher temperatures, but not prematurely. If the proper grade of fuel is not available, use the next higher grade as a substitute. Never use a grade lower than recommended. This can cause the cylinder head temperature and engine oil temperature to exceed their normal operating ranges, which may result in detonation.

Several grades of AVGAS are available. Care must be exercised to ensure that the correct aviation grade is being used for the specific type of engine. The proper fuel grade is stated in the AFM/POH, on placards in the flight deck, and next to the filler caps. Automobile gas should NEVER be used in aircraft engines unless the aircraft has been modified with a Supplemental Type Certificate (STC) issued by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

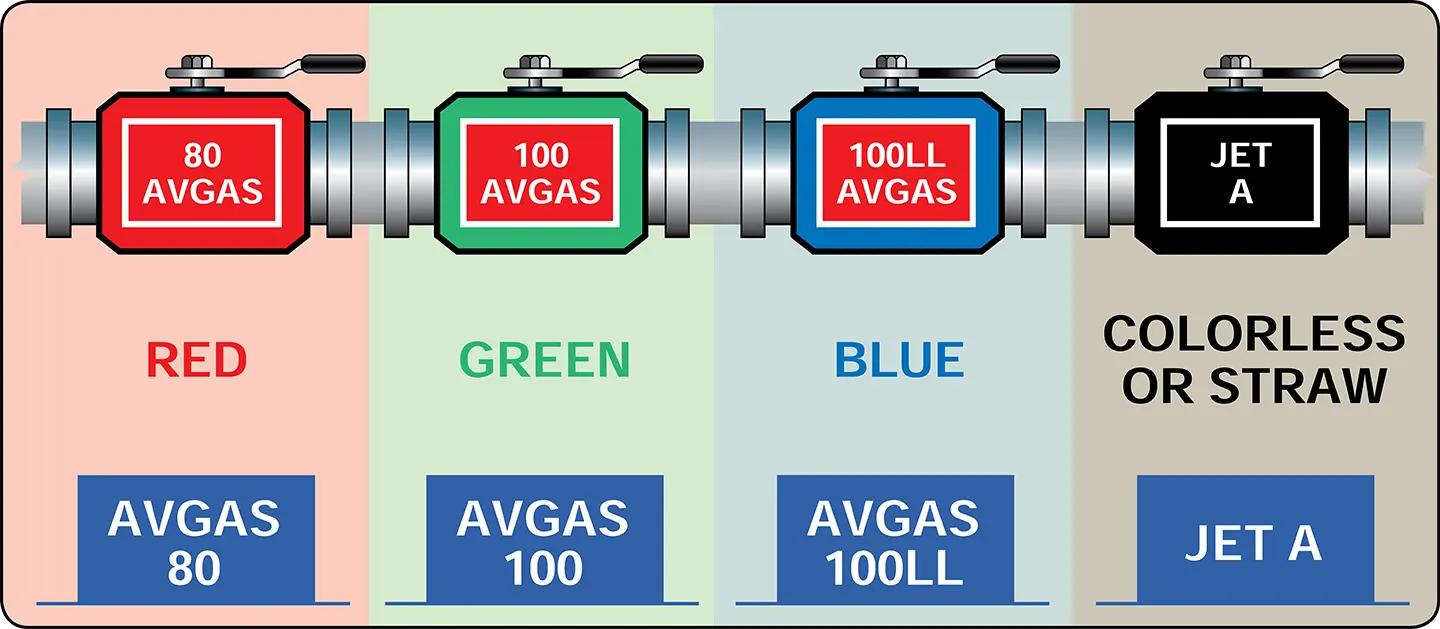

The current method identifies AVGAS for aircraft with reciprocating engines by the octane and performance number, along with the abbreviation AVGAS. These aircraft use AVGAS 80, 100, and 100LL. Although AVGAS 100LL performs the same as grade 100, the “LL” indicates it has a low lead content. Fuel for aircraft with turbine engines is classified as JET A, JET A-1, and JET B. Jet fuel is basically kerosene and has a distinctive kerosene smell. Since use of the correct fuel is critical, dyes are added to help identify the type and grade of fuel. [Figure 3]

In addition to the color of the fuel itself, the color-coding system extends to decals and various airport fuel handling equipment. For example, all AVGAS is identified by name, using white letters on a red background. In contrast, turbine fuels are identified by white letters on a black background.

Special Airworthiness Information Bulleting (SAIB) NE-11-15 advises that grade 100VLL AVGAS is acceptable for use on aircraft and engines. 100VLL meets all performance requirements of grades 80, 91, 100, and 100LL; meets the approved operating limitations for aircraft and engines certificated to operate with these other grades of AVGAS; and is basically identical to 100LL AVGAS. The lead content of 100VLL is reduced by about 19 percent. 100VLL is blue like 100LL and virtually indistinguishable.

Fuel Contamination

Accidents attributed to powerplant failure from fuel contamination have often been traced to:

- Inadequate preflight inspection by the pilot

- Servicing aircraft with improperly filtered fuel from small tanks or drums

- Storing aircraft with partially filled fuel tanks

- Lack of proper maintenance

Fuel should be drained from the fuel strainer quick drain and from each fuel tank sump into a transparent container and then checked for dirt and water. When the fuel strainer is being drained, water in the tank may not appear until all the fuel has been drained from the lines leading to the tank. This indicates that water remains in the tank and is not forcing the fuel out of the fuel lines leading to the fuel strainer. Therefore, drain enough fuel from the fuel strainer to be certain that fuel is being drained from the tank. The amount depends on the length of fuel line from the tank to the drain. If water or other contaminants are found in the first sample, drain further samples until no trace appears.

Water may also remain in the fuel tanks after the drainage from the fuel strainer has ceased to show any trace of water. This residual water can be removed only by draining the fuel tank sump drains.

Water is the principal fuel contaminant. Suspended water droplets in the fuel can be identified by a cloudy appearance of the fuel, or by the clear separation of water from the colored fuel, which occurs after the water has settled to the bottom of the tank. As a safety measure, the fuel sumps should be drained before every flight during the preflight inspection.

Fuel tanks should be filled after each flight or after the last flight of the day to prevent moisture condensation within the tank. To prevent fuel contamination, avoid refueling from cans and drums.

In remote areas or in emergency situations, there may be no alternative to refueling from sources with inadequate anti-contamination systems. While a chamois skin and funnel may be the only possible means of filtering fuel, using them is hazardous. Remember, the use of a chamois does not always ensure decontaminated fuel. Worn-out chamois do not filter water; neither will a new, clean chamois that is already water-wet or damp. Most imitation chamois skins do not filter water.

Fuel System Icing

Ice formation in the aircraft fuel system results from the presence of water in the fuel system. This water may be undissolved or dissolved. One condition of undissolved water is entrained water that consists of minute water particles suspended in the fuel. This may occur as a result of mechanical agitation of free water or conversion of dissolved water through temperature reduction. Entrained water settles out in time under static conditions and may or may not be drained during normal servicing, depending on the rate at which it is converted to free water. In general, it is not likely that all entrained water can ever be separated from fuel under field conditions. The settling rate depends on a series of factors including temperature, quiescence, and droplet size.

The droplet size varies depending upon the mechanics of formation. Usually, the particles are so small as to be invisible to the naked eye, but in extreme cases, can cause slight haziness in the fuel. Water in solution cannot be removed except by dehydration or by converting it through temperature reduction to entrained, then to free water.

Another condition of undissolved water is free water that may be introduced as a result of refueling or the settling of entrained water that collects at the bottom of a fuel tank. Free water is usually present in easily detected quantities at the bottom of the tank, separated by a continuous interface from the fuel above. Free water can be drained from a fuel tank through the sump drains, which are provided for that purpose. Free water, frozen on the bottom of reservoirs, such as the fuel tanks and fuel filter, may render water drains useless and can later melt releasing the water into the system thereby causing engine malfunction or stoppage. If such a condition is detected, the aircraft may be placed in a warm hangar to reestablish proper draining of these reservoirs, and all sumps and drains should be activated and checked prior to flight.

Entrained water (i.e., water in solution with petroleum fuels) constitutes a relatively small part of the total potential water in a particular system, the quantity dissolved being dependent on fuel temperature and the existing pressure and the water volubility characteristics of the fuel. Entrained water freezes in mid fuel and tends to stay in suspension longer since the specific gravity of ice is approximately the same as that of AVGAS.

Water in suspension may freeze and form ice crystals of sufficient size such that fuel screens, strainers, and filters may be blocked. Some of this water may be cooled further as the fuel enters carburetor air passages and causes carburetor metering component icing, when conditions are not otherwise conducive to this form of icing.

Prevention Procedures

The use of anti-icing additives for some aircraft has been approved as a means of preventing problems with water and ice in AVGAS. Some laboratory and flight testing indicates that the use of hexylene glycol, certain methanol derivatives, and ethylene glycol mononethyl ether (EGME) in small concentrations inhibit fuel system icing. These tests indicate that the use of EGME at a maximum 0.15 percent by volume concentration substantially inhibits fuel system icing under most operating conditions. The concentration of additives in the fuel is critical. Marked deterioration in additive effectiveness may result from too little or too much additive. Pilots should recognize that anti-icing additives are in no way a substitute or replacement for carburetor heat. Aircraft operating instructions involving the use of carburetor heat should be adhered to at all times when operating under atmospheric conditions conducive to icing.