The Earth is a huge magnet, spinning in space, surrounded by a magnetic field made up of invisible lines of flux. These lines leave the surface at the magnetic North Pole and reenter at the magnetic South Pole.

Lines of magnetic flux have two important characteristics: any magnet that is free to rotate will align with them, and an electrical current is induced into any conductor that cuts across them. Most direction indicators installed in aircraft make use of one of these two characteristics.

Magnetic Compass

One of the oldest and simplest instruments for indicating direction is the magnetic compass. It is also one of the basic instruments required by Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) part 91 for both VFR and IFR flight.

A magnet is a piece of material, usually a metal containing iron, that attracts and holds lines of magnetic flux. Regardless of size, every magnet has two poles: north and south. When one magnet is placed in the field of another, the unlike poles attract each other, and like poles repel.

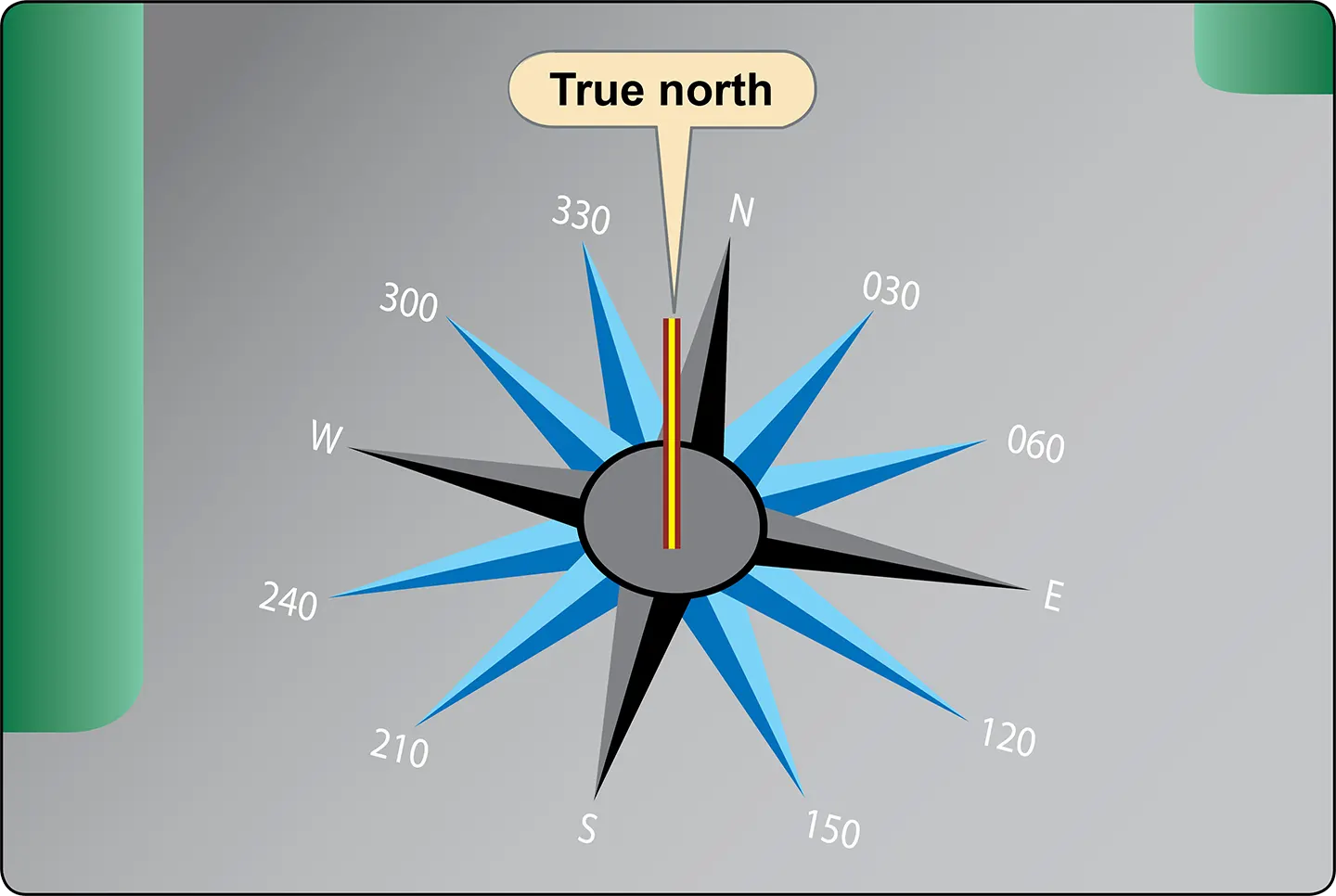

An aircraft magnetic compass, such as the one in Figure 1, has two small magnets attached to a metal float sealed inside a bowl of clear compass fluid similar to kerosene. A graduated scale, called a card, is wrapped around the float and viewed through a glass window with a lubber line across it. The card is marked with letters representing the cardinal directions, north, east, south, and west, and a number for each 30° between these letters. The final “0” is omitted from these directions. For example, 3 = 30°, 6 = 60°, and 33 = 330°.

There are long and short graduation marks between the letters and numbers, each long mark representing 10° and each short mark representing 5°.

The float and card assembly has a hardened steel pivot in its center that rides inside a special, spring-loaded, hard glass jewel cup. The buoyancy of the float takes most of the weight off of the pivot, and the fluid damps the oscillation of the float and card. This jewel-and-pivot type mounting allows the float freedom to rotate and tilt up to approximately 18° angle of bank. At steeper bank angles, the compass indications are erratic and unpredictable.

The compass housing is entirely full of compass fluid. To prevent damage or leakage when the fluid expands and contracts with temperature changes, the rear of the compass case is sealed with a flexible diaphragm, or with a metal bellows in some compasses.

The magnets align with the Earth’s magnetic field and the pilot reads the direction on the scale opposite the lubber line. Note that in Figure 1, the pilot views the compass card from its backside. When the pilot is flying north, as the compass indicates, east is to the pilot’s right. On the card, “33,” which represents 330° (west of north), is to the right of north. The reason for this apparent backward graduation is that the card remains stationary, and the compass housing and the pilot rotate around it. Because of this setup, the magnetic compass can be confusing to read.

Magnetic Compass Induced Errors

The magnetic compass is the simplest instrument in the panel, but it is subject to a number of errors that must be considered.

Variation

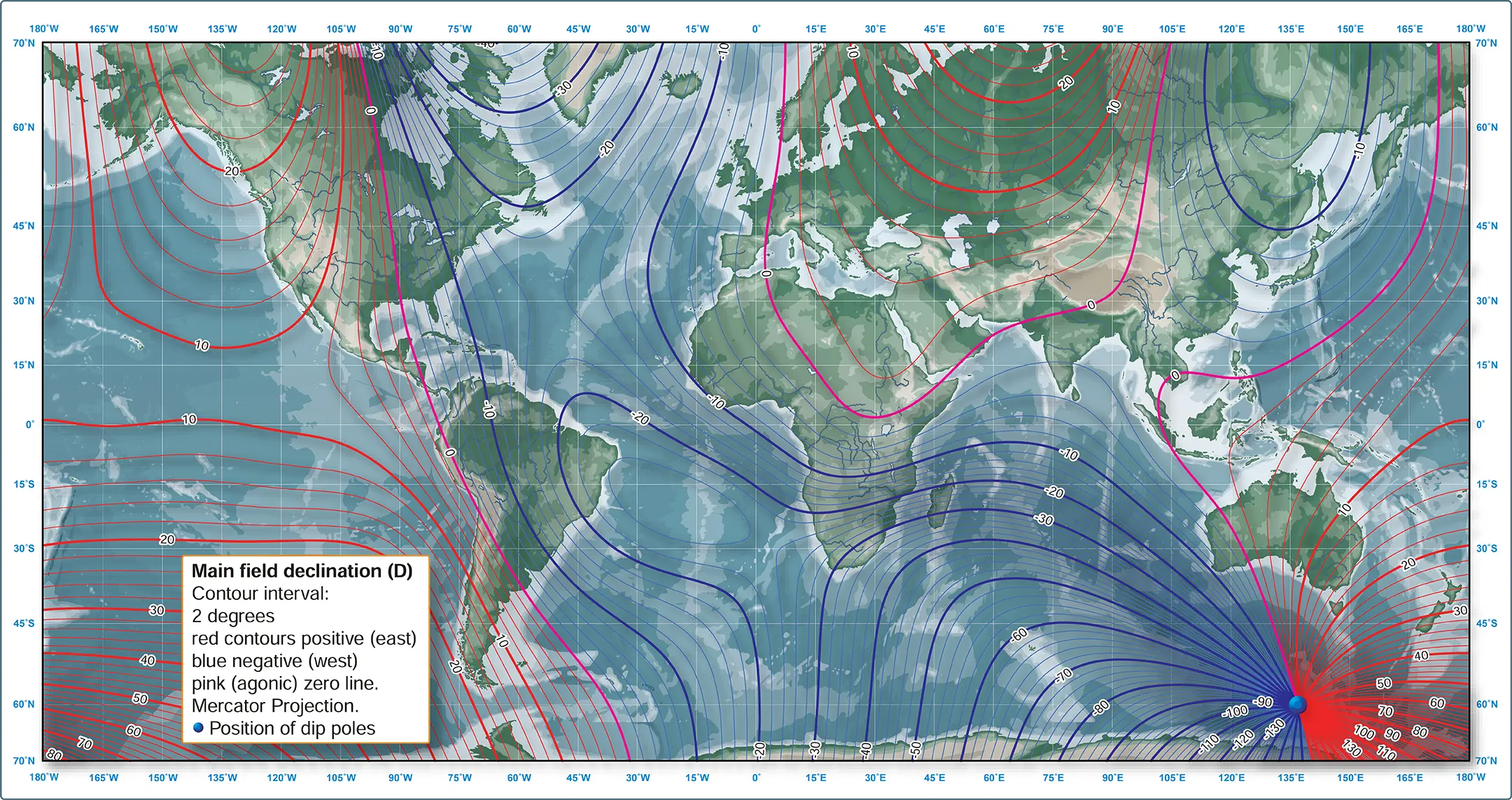

The Earth rotates about its geographic axis; maps and charts are drawn using meridians of longitude that pass through the geographic poles. Directions measured from the geographic poles are called true directions. The magnetic North Pole to which the magnetic compass points is not collocated with the geographic North Pole, but is some 1,300 miles away; directions measured from the magnetic poles are called magnetic directions. In aerial navigation, the difference between true and magnetic directions is called variation. This same angular difference in surveying and land navigation is called declination.

Figure 2 shows the isogonic lines that identify the number of degrees of variation in their area. The line that passes near Chicago is called the agonic line. Anywhere along this line the two poles are aligned, and there is no variation. East of this line, the magnetic North Pole is to the west of the geographic North Pole and a correction must be applied to a compass indication to get a true direction.

Flying in the Washington, D.C., area, for example, the variation is 10° west. If a pilot wants to fly a true course of south (180°), the variation must be added to this, resulting in a magnetic course of 190° to fly. Flying in the Los Angeles, California area, the variation is 14° east. To fly a true course of 180° there, the pilot would have to subtract the variation and fly a magnetic course of 166°. The variation error does not change with the heading of the aircraft; it is the same anywhere along the isogonic line.

Deviation

The magnets in a compass align with any magnetic field. Some causes for magnetic fields in aircraft include flowing electrical current, magnetized parts, and conflict with the Earth’s magnetic field. These aircraft magnetic fields create a compass error called deviation.

Deviation, unlike variation, depends on the aircraft heading. Also unlike variation, the aircraft’s geographic location does not affect deviation. While no one can reduce or change variation error, an aviation maintenance technician (AMT) can provide the means to minimize deviation error by performing the maintenance task known as “swinging the compass.”

To swing the compass, an AMT positions the aircraft on a series of known headings, usually at a compass rose. [Figure 3] A compass rose consists of a series of lines marked every 30° on an airport ramp, oriented to magnetic north. There is minimal magnetic interference at the compass rose. The pilot or the AMT, if authorized, can taxi the aircraft to the compass rose and maneuver the aircraft to the headings prescribed by the AMT.

As the aircraft is “swung” or aligned to each compass rose heading, the AMT adjusts the compensator assembly located on the top or bottom of the compass. The compensator assembly has two shafts whose ends have screwdriver slots accessible from the front of the compass. Each shaft rotates one or two small compensating magnets. The end of one shaft is marked E-W, and its magnets affect the compass when the aircraft is pointed east or west. The other shaft is marked N-S and its magnets affect the compass when the aircraft is pointed north or south.

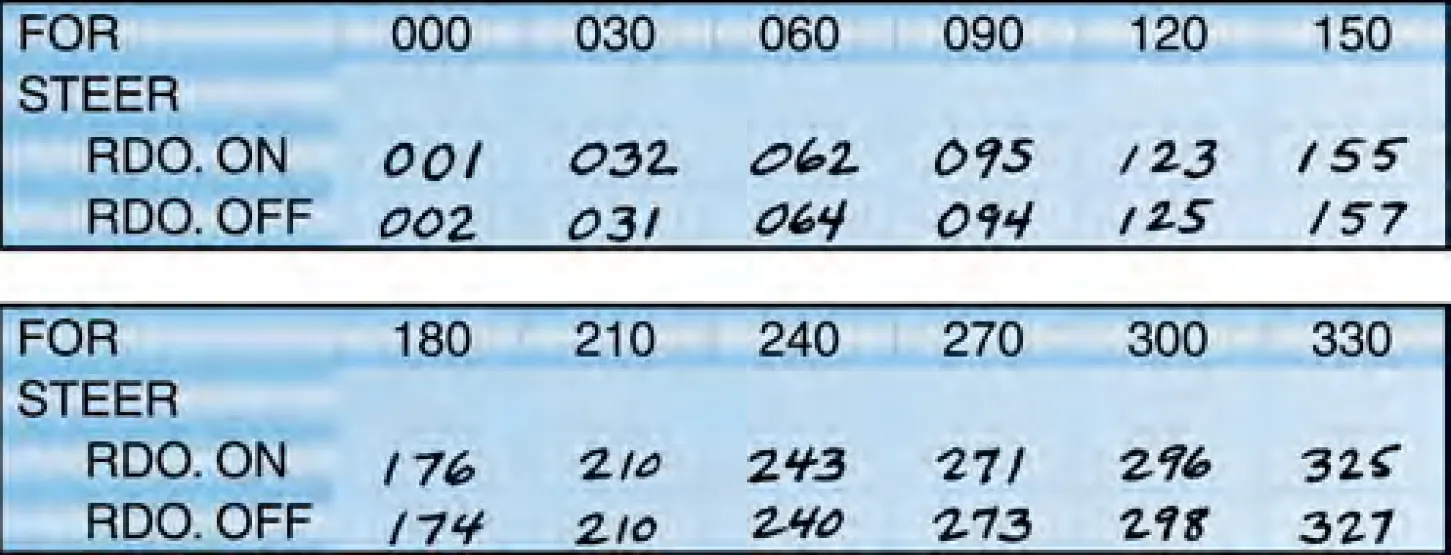

The adjustments position the compensating magnets to minimize the difference between the compass indication and the actual aircraft magnetic heading. The AMT records any remaining error on a compass correction card like the one in Figure 4 and places it in a holder near the compass. Only AMTs can adjust the compass or complete the compass correction card. Pilots determine and fly compass headings using the deviation errors noted on the card. Pilots must also note the use of any equipment causing operational magnetic interference such as radios, deicing equipment, pitot heat, radar, or magnetic cargo.

The corrections for variation and deviation must be applied in the correct sequence as shown below, starting from the true course desired.

Step 1: Determine the Magnetic Course

True Course (180°) ± Variation (+10°) = Magnetic Course (190°)

The magnetic course (190°) is steered if there is no deviation error to be applied. The compass card must now be considered for the compass course of 190°.

Step 2: Determine the Compass Course

Magnetic Course (190°, from step 1) ± Deviation (–2°, from correction card) = Compass Course (188°)

NOTE: Intermediate magnetic courses between those listed on the compass card need to be interpreted. Therefore, to steer a true course of 180°, the pilot would follow a compass course of 188°.

To find the true course that is being flown when the compass course is known:

Compass Course ± Deviation = Magnetic Course ± Variation= True Course

Dip Errors

The Earth’s magnetic field runs parallel to its surface only at the Magnetic Equator, which is the point halfway between the Magnetic North and South Poles. As you move away from the Magnetic Equator towards the magnetic poles, the angle created by the vertical pull of the Earth’s magnetic field in relation to the Earth’s surface increases gradually. This angle is known as the dip angle. The dip angle increases in a downward direction as you move towards the Magnetic North Pole and increases in an upward direction as you move towards the Magnetic South Pole.

If the compass needle were mounted so that it could pivot freely in three dimensions, it would align itself with the magnetic field, pointing up or down at the dip angle in the direction of local Magnetic North. Because the dip angle is of no navigational interest, the compass is made so that it can rotate only in the horizontal plane. This is done by lowering the center of gravity below the pivot point and making the assembly heavy enough that the vertical component of the magnetic force is too weak to tilt it significantly out of the horizontal plane. The compass can then work effectively at all latitudes without specific compensation for dip. However, close to the magnetic poles, the horizontal component of the Earth’s field is too small to align the compass which makes the compass unusable for navigation. Because of this constraint, the compass only indicates correctly if the card is horizontal. Once tilted out of the horizontal plane, it will be affected by the vertical component of the Earth’s field which leads to the following discussions on northerly and southerly turning errors.

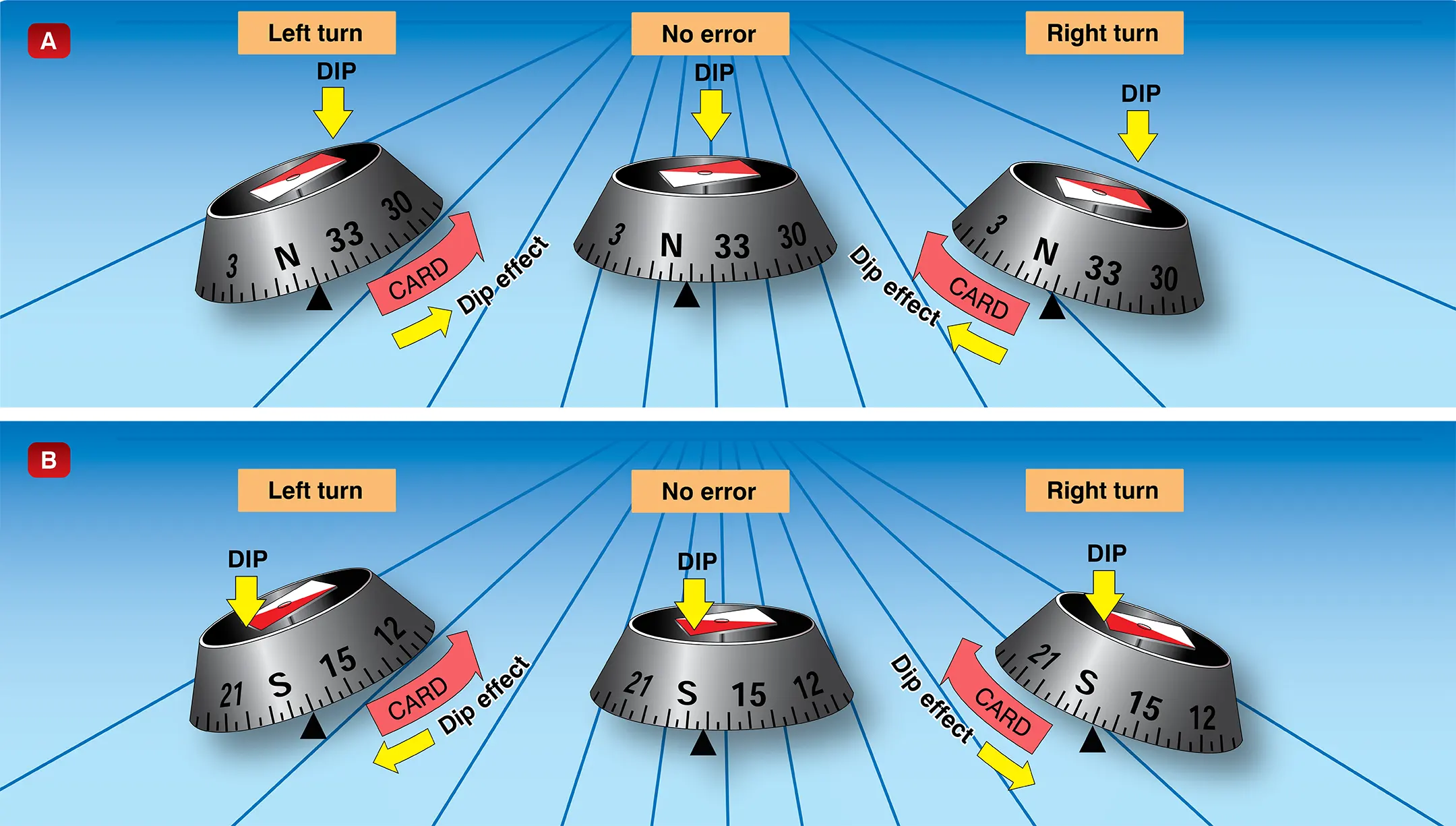

Northerly Turning Errors

The center of gravity of the float assembly is located lower than the pivotal point. As the aircraft turns, the force that results from the magnetic dip causes the float assembly to swing in the same direction that the float turns. The result is a false northerly turn indication. Because of this lead of the compass card, or float assembly, a northerly turn should be stopped prior to arrival at the desired heading. This compass error is amplified with the proximity to either magnetic pole. One rule of thumb to correct for this leading error is to stop the turn 15 degrees plus half of the latitude (i.e., if the aircraft is being operated in a position near 40 degrees latitude, the turn should be stopped 15+20=35 degrees prior to the desired heading). [Figure 5A]

Southerly Turning Errors

When turning in a southerly direction, the forces are such that the compass float assembly lags rather than leads. The result is a false southerly turn indication. The compass card, or float assembly, should be allowed to pass the desired heading prior to stopping the turn. As with the northerly error, this error is amplified with the proximity to either magnetic pole. To correct this lagging error, the aircraft should be allowed to pass the desired heading prior to stopping the turn. The same rule of 15 degrees plus half of the latitude applies here (i.e., if the aircraft is being operated in a position near 30 degrees latitude, the turn should be stopped 15+15+30 degrees after passing the desired heading). [Figure 5B]

Acceleration Error

The magnetic dip and the forces of inertia cause magnetic compass errors when accelerating and decelerating on easterly and westerly headings. Because of the pendulous-type mounting, the aft end of the compass card is tilted upward when accelerating and downward when decelerating during changes of airspeed. When accelerating on either an easterly or westerly heading, the error appears as a turn indication toward north. When decelerating on either of these headings, the compass indicates a turn toward south. A mnemonic, or memory jogger, for the effect of acceleration error is the word “ANDS” (Acceleration- North/Deceleration-South) may help you to remember the acceleration error. [Figure 6] Acceleration causes an indication toward north; deceleration causes an indication toward south.

Oscillation Error

Oscillation is a combination of all of the errors previously mentioned and results in fluctuation of the compass card in relation to the actual heading direction of the aircraft. When setting the gyroscopic heading indicator to agree with the magnetic compass, use the average indication between the swings.

The Vertical Card Magnetic Compass

The vertical card magnetic compass eliminates some of the errors and confusion encountered with the magnetic compass. The dial of this compass is graduated with letters representing the cardinal directions, numbers every 30°, and tick marks every 5°. The dial is rotated by a set of gears from the shaft-mounted magnet, and the nose of the symbolic aircraft on the instrument glass represents the lubber line for reading the heading of the aircraft from the dial. [Figure 7]

Lags or Leads

When starting a turn from a northerly heading, the compass lags behind the turn. When starting a turn from a southerly heading, the compass leads the turn.

Eddy Current Damping

In the case of a vertical card magnetic compass, flux from the oscillating permanent magnet produces eddy currents in a damping disk or cup. The magnetic flux produced by the eddy currents opposes the flux from the permanent magnet and decreases the oscillations.