Horizontal Situation Indicator (HSI)

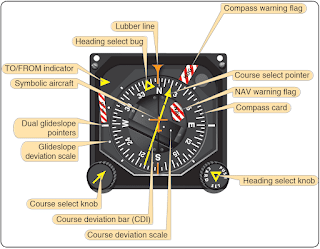

The HSI is a direction indicator that uses the output from a flux valve to drive the dial, which acts as the compass card. This instrument, shown in Figure 1, combines the magnetic compass with navigation signals and a glideslope. This gives the pilot an indication of the location of the aircraft with relationship to the chosen course.

|

| Figure 1. Horizontal situation indicator (HSI) |

In Figure 1, the aircraft heading displayed on the rotating azimuth card under the upper lubber line is North or 360°. The course-indicating arrowhead shown is set to 020; the tail indicates the reciprocal, 200°. The course deviation bar operates with a VOR/Localizer (VOR/LOC) navigation receiver to indicate left or right deviations from the course selected with the course-indicating arrow, operating in the same manner that the angular movement of a conventional VOR/LOC needle indicates deviation from course.

Attitude Direction Indicator (ADI)

Advances in attitude instrumentation combine the gyro horizon with other instruments such as the HSI, thereby reducing the number of separate instruments to which the pilot must devote attention. The attitude direction indicator (ADI) is an example of such technological advancement. A flight director incorporates the ADI within its system, which is further explained below (Flight Director System). However, an ADI need not have command cues; however, it is normally equipped with this feature.

Flight Director System (FDS)

A Flight Director System (FDS) combines many instruments into one display that provides an easily interpreted understanding of the aircraft’s flightpath. The computed solution furnishes the steering commands necessary to obtain and hold a desired path.

Major components of an FDS include an ADI, also called a Flight Director Indicator (FDI), an HSI, a mode selector, and a flight director computer. It should be noted that a flight director in use does not infer the aircraft is being manipulated by the autopilot (coupled), but is providing steering commands that the pilot (or the autopilot, if coupled) follows.

Typical flight directors use one of two display systems for steerage. The first is a set of command bars, one horizontal and one vertical. The command bars in this configuration are maintained in a centered position (much like a centered glideslope). The second uses a miniature aircraft aligned to a command cue.

|

| Figure 2. A typical cue that a pilot would follow |

One of the first widely used flight directors was developed by Sperry and was called the Sperry Three Axis Attitude Reference System (STARS). Developed in the 1960s, it was commonly found on both commercial and business aircraft alike. STARS (with a modification) and successive flight directors were integrated with the autopilots and aircraft providing a fully integrated flight system.

The flight director/autopilot system described below is typical of installations in many general aviation aircraft. The components of a typical flight director include the mode controller, ADI, HSI, and annunciator panel. These units are illustrated in Figure 3.

|

| Figure 3. Components of a typical FDS |

The pilot may choose from among many modes including the HDG (heading) mode, the VOR/LOC (localizer tracking) mode, or the AUTO Approach (APP) or G/S (automatic capture and tracking of instrument landing system (ILS) localizers and glidepath) mode. The auto mode has a fully automatic pitch selection computer that takes into account aircraft performance and wind conditions, and operates once the pilot has reached the ILS glideslope. More sophisticated systems allow more flight director modes.

Integrated Flight Control System

The integrated flight control system integrates and merges various systems into a system operated and controlled by one principal component. Figure 4 illustrates key components of the flight control system that was developed from the onset as a fully integrated system comprised of the airframe, autopilot, and FDS. This trend of complete integration, once seen only in large commercial aircraft, is now becoming common in general aviation.

|

| Figure 4. The S-TEC/Meggit Corporation Integrated Autopilot installed in the Cirrus |

Autopilot Systems

An autopilot is a mechanical means to control an aircraft using electrical, hydraulic, or digital systems. Autopilots can control three axes of the aircraft: roll, pitch, and yaw. Most autopilots in general aviation control roll and pitch.

Autopilots also function using different methods. The first is position based. That is, the attitude gyro senses the degree of difference from a position such as wings level, a change in pitch, or a heading change.

Determining whether a design is position based and/or rate based lies primarily within the type of sensors used. In order for an autopilot to possess the capability of controlling an aircraft’s attitude (i.e., roll and pitch), that system must be provided with constant information on the actual attitude of that aircraft. This is accomplished by the use of several different types of gyroscopic sensors. Some sensors are designed to indicate the aircraft’s attitude in the form of position in relation to the horizon, while others indicate rate (position change over time).

|

| Figure 5. An Autopilot by Century |

Figure 6 is a diagram layout of a rate-based autopilot by S-Tec, which permits the purchaser to add modular capability form basic wing leveling to increased capability.

|

| Figure 6. A diagram layout of an autopilot by S-Tec |