In addition to learning to make good aeronautical decisions, and learning to manage risk and flight workload, situation awareness (SA) is an important element of ADM. Situational awareness is the accurate perception and understanding of all the factors and conditions within the four fundamental risk elements (PAVE) that affect safety before, during, and after the flight. Situation awareness (SA) involves being aware of what is happening around you to understand how information, events, and your own actions will impact your goals and objectives, both now and in the near future. Lacking SA or having inadequate SA has been identified as one of the primary factors in accidents attributed to human error.

Situational awareness in a helicopter can be quickly lost. Understanding the significance and impact of each risk factor independently and cumulatively aid in safe flight operations. It is possible, and all too likely, that we forget flying while at work. Our occupation, or work, may be conducting long line operations, maneuvering around city obstacles to allow a film crew access to news events, spraying crops, ferrying passengers or picking up a patient to be flown to a hospital. In each case we are flying a helicopter. The moment we fail to account for the aircraft systems, the environment, other aircraft, hazards, and ourselves, we lose situational awareness.

Obstacles to Maintaining Situational Awareness

What distractions interfere with our focus or train of thought? There are many. A few examples pertinent to aviation, and helicopters specifically, follow.

Fatigue, frequently associated with pilot error, is a threat to aviation safety because it impairs alertness and performance. [Figure 1] The term is used to describe a range of experiences from sleepy or tired to exhausted. Two major physiological phenomena create fatigue: circadian rhythm disruption and sleep loss.

|

| Figure 1. Warning signs of fatigue according to the FAA Civil Aerospace Medical Institute (CAMI) |

|

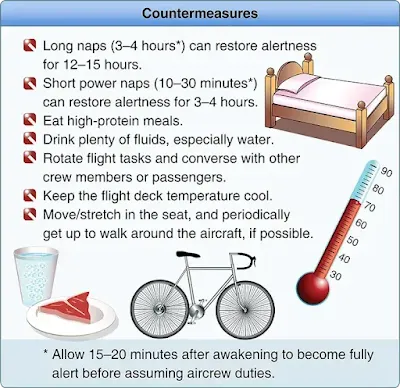

| Figure 2. Countermeasures to fatigue according to the FAA Civil Aerospace Medical Institute (CAMI) |

Complacent acceptance of common weather patterns can have huge impacts on safety. The forecast was for clearing after the rain shower, but what was the dew-point spread? The winds are greater than forecast. Will this create reduced visibility in dusty, snowy areas or exceed wind limitations?

While conducting crop spraying, a new agent is used. Does that change the weight? Does that change the flight profile and, if so, what new hazards might be encountered? When things are going smoothly, it is time to heighten your awareness and become more attentive to your flight activities.

Advanced avionics have created a high degree of redundancy and dependability in modern aircraft systems, which can promote complacency and inattention. Routine flight operations may lead to a sense of complacency, which can threaten flight safety by reducing situational awareness.

Loss of situational awareness can be caused by a minor distraction that diverts the pilot’s attention from monitoring the instruments or scanning outside the aircraft. For example, a gauge that is not reading correctly is a minor problem, but it can cause an accident if the pilot diverts attention to the perceived problem and neglects to control the aircraft properly.

Operational Pitfalls

There are numerous classic behavioral traps that can ensnare the unwary pilot. Pilots, particularly those with considerable experience, try to complete a flight as planned, please passengers, and meet schedules. This basic drive to achieve can have an adverse effect on safety and can impose an unrealistic assessment of piloting skills under stressful conditions. These tendencies ultimately may bring about practices that are dangerous and sometimes illegal, and may lead to a mishap. Pilots develop awareness and learn to avoid many of these operational pitfalls through effective SRM training. [Figure 3]

| Operational Pitfalls |

|---|

| Peer Pressure It would be foolish and unsafe for a new pilot to attempt to compete with an older, more experienced pilot. The only safe competition should be completing the most safe flights with no one endangered or hurt and the aircraft returned to service. Efficiency comes with experience and on-the-job training. |

| Mind Set A pilot should be taught to approach every day as something new. |

| Get-There-Itis This disposition impairs pilot judgment through a fixation on the original goal or destination, combined with a disregard for any alternative course of action. |

| Duck-Under Syndrome A pilot may be tempted to arrive at an airport by descending below minimums during an approach. There may be a belief that there is a built-in margin of error in every approach procedure, or the pilot may not want to admit that the landing cannot be completed and a missed approach must be initiated. |

| Scud Running It is difficult for a pilot to estimate the distance from indistinct forms, such as clouds or fog formation. |

| Continuing Visual Flight Rules (VFR) Into Instrument Conditions Spatial disorientation or collision with ground/obstacles may occur when a pilot continues VFR into instrument conditions. This can be even more dangerous if the pilot is not instrument rated or current. |

| Getting Behind the Aircraft This pitfall can be caused by allowing events or the situation to control pilot actions. A constant state of surprise at what happens next may be exhibited when the pilot is “getting behind” the aircraft. |

| Loss of Positional or Situational Awareness In extreme cases of a pilot getting behind the aircraft, a loss of positional or situational awareness may result. The pilot may not know the aircraft’s geographical location, or may be unable to recognize deteriorating circumstances. |

| Operating Without Adequate Fuel Reserves Pilots should use the last of the known fuel to make a safe landing. Bringing fuel to an aircraft is much less inconvenient than picking up the pieces of a crashed helicopter! Pilots should land prior to whenever their watch, fuel gauge, low-fuel warning system, or flight planning indicates fuel burnout. They should always be thinking of unforecast winds, richer-than-planned mixtures, unknown leaks, mis-servicing, and errors in planning. Newer pilots need to be wary of fuselage attitudes in low-fuel situations. Some helicopters can port air into the fuel system in low-fuel states, causing the engines to quit or surge. |

| Descent Below the Minimum En Route Altitude The duck-under syndrome, as mentioned above, can also occur during the en route portion of an IFR flight. |

| Flying Outside the Envelope The pilot must understand how to check the charts, understand the results, and fly accordingly. |

| Neglect of Flight Planning, Preflight Inspections, and Checklists All pilots and operators must understand the complexity of the helicopter, the amazing number of parts, and why there are service times associated with certain parts. Pilots should understand material fatigue and maintenance requirements. Helicopters are unforgiving of disregarded maintenance requirements. Inspections and maintenance are in place for safety; something functioning improperly can be the first link in the error chain to an accident. In some cases, proper maintenance is a necessary condition for insurance coverage. |