The burning fuel within the cylinders produces intense heat, most of which is expelled through the exhaust system. Much of the remaining heat, however, must be removed, or at least dissipated, to prevent the engine from overheating. Otherwise, the extremely high engine temperatures can lead to loss of power, excessive oil consumption, detonation, and serious engine damage.

While the oil system is vital to the internal cooling of the engine, an additional method of cooling is necessary for the engine’s external surface. Most small aircraft are air cooled, although some are liquid cooled.

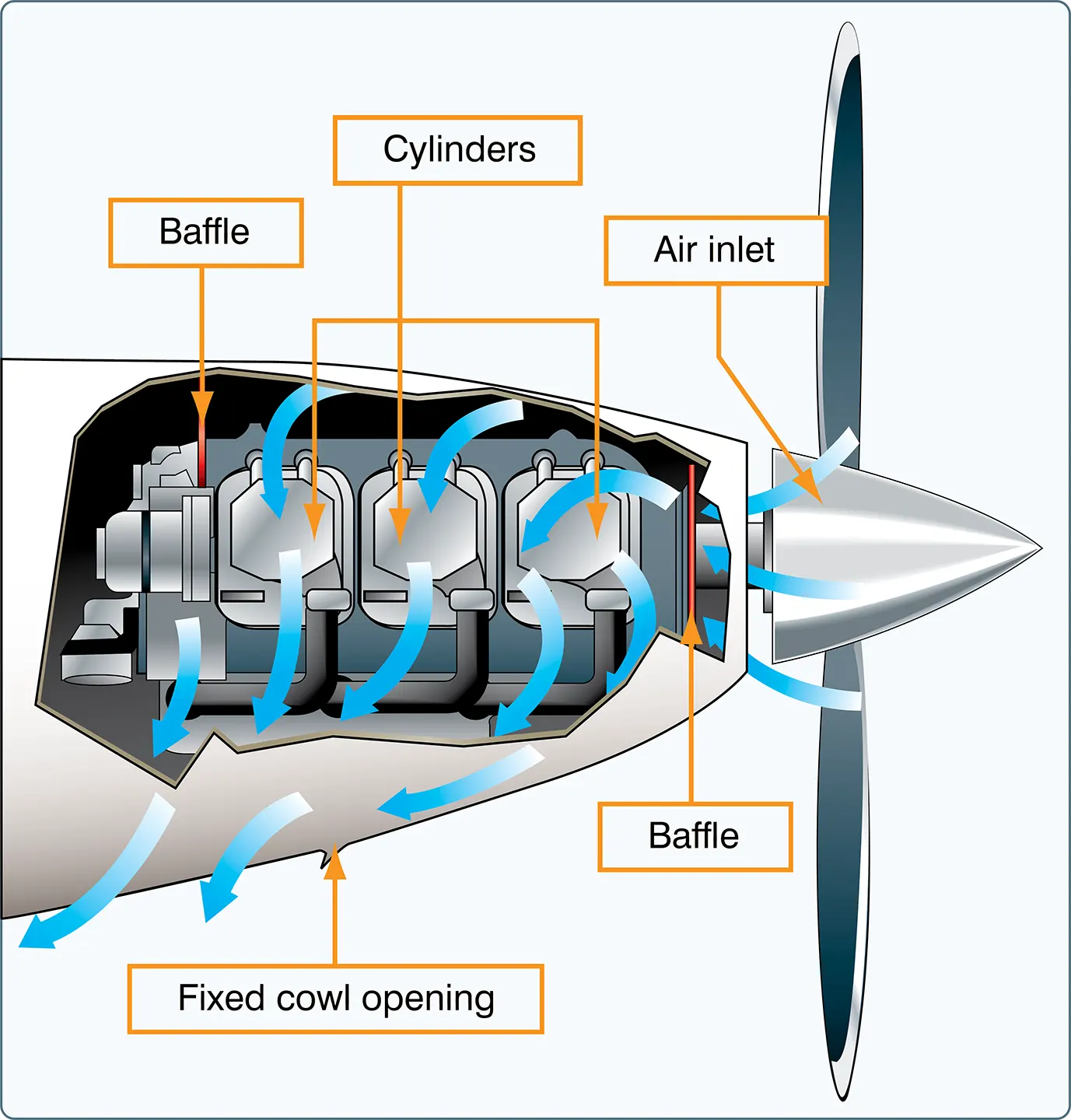

Air cooling is accomplished by air flowing into the engine compartment through openings in front of the engine cowling. Baffles route this air over fins attached to the engine cylinders, and other parts of the engine, where the air absorbs the engine heat. Expulsion of the hot air takes place through one or more openings in the lower, aft portion of the engine cowling. [Figure]

The outside air enters the engine compartment through an inlet behind the propeller hub. Baffles direct it to the hottest parts of the engine, primarily the cylinders, which have fins that increase the area exposed to the airflow.

The air cooling system is less effective during ground operations, takeoffs, go-arounds, and other periods of high-power, low-airspeed operation. Conversely, high-speed descents provide excess air and can shock cool the engine, subjecting it to abrupt temperature fluctuations.

Operating the engine at higher than its designed temperature can cause loss of power, excessive oil consumption, and detonation. It will also lead to serious permanent damage, such as scoring the cylinder walls, damaging the pistons and rings, and burning and warping the valves. Monitoring the flight deck engine temperature instruments aids in avoiding high operating temperature.

Under normal operating conditions in aircraft not equipped with cowl flaps, the engine temperature can be controlled by changing the airspeed or the power output of the engine. High engine temperatures can be decreased by increasing the airspeed and/or reducing the power.

The oil temperature gauge gives an indirect and delayed indication of rising engine temperature, but can be used for determining engine temperature if this is the only means available.

Most aircraft are equipped with a cylinder-head temperature gauge that indicates a direct and immediate cylinder temperature change. This instrument is calibrated in degrees Celsius or Fahrenheit and is usually color coded with a green arc to indicate the normal operating range. A red line on the instrument indicates maximum allowable cylinder head temperature.

To avoid excessive cylinder head temperatures, increase airspeed, enrich the fuel-air mixture, and/or reduce power. Any of these procedures help to reduce the engine temperature. On aircraft equipped with cowl flaps, use the cowl flap positions to control the temperature. Cowl flaps are hinged covers that fit over the opening through which the hot air is expelled. If the engine temperature is low, the cowl flaps can be closed, thereby restricting the flow of expelled hot air and increasing engine temperature. If the engine temperature is high, the cowl flaps can be opened to permit a greater flow of air through the system, thereby decreasing the engine temperature.