The two basic methods used for learning attitude instrument flying are “control and performance” and “primary and supporting.” Both methods utilize the same instruments and responses for attitude control. They differ in their reliance on the attitude indicator and interpretation of other instruments.

Attitude Instrument Flying Using the Control and Performance Method

Aircraft performance is achieved by controlling the aircraft attitude and power. Aircraft attitude is the relationship of both the aircraft’s pitch and roll axes in relation to the Earth’s horizon. An aircraft is flown in instrument flight by controlling the attitude and power, as necessary, to produce both controlled and stabilized flight without reference to a visible horizon. This overall process is known as the control and performance method of attitude instrument flying. Starting with basic instrument maneuvers, this process can be applied through the use of control, performance, and navigation instruments resulting in a smooth flight from takeoff to landing.

Control Instruments

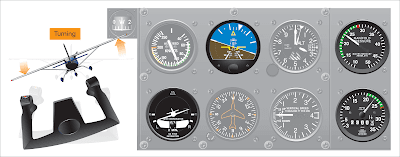

The control instruments display immediate attitude and power indications and are calibrated to permit those respective adjustments in precise increments. In this discussion, the term “power” is used in place of the more technically correct term “thrust or drag relationship.” Control is determined by reference to the attitude and power indicators. Power indicators vary with aircraft and may include manifold pressure, tachometers, fuel flow, etc. [Figure 1]

|

| Figure 1. Control instruments |

Performance Instruments

The performance instruments indicate the aircraft’s actual performance. Performance is determined by reference to the altimeter, airspeed, or vertical speed indicator (VSI). [Figure 2]

|

| Figure 2. Performance instruments |

Navigation Instruments

The navigation instruments indicate the position of the aircraft in relation to a selected navigation facility or fix. This group of instruments includes various types of course indicators, range indicators, glideslope indicators, and bearing pointers. [Figure 3] Newer aircraft with more technologically advanced instrumentation provide blended information, giving the pilot more accurate positional information.

|

| Figure 3. Navigation instruments |

Procedural Steps in Using Control and Performance

- Establish an attitude and power setting on the control instruments that results in the desired performance. Known or computed attitude changes and approximated power settings helps to reduce the pilot’s workload.

- Trim (fine tune the control forces) until control pressures are neutralized. Trimming for hands-off flight is essential for smooth, precise aircraft control. It allows a pilot to attend to other flight deck duties with minimum deviation from the desired attitude.

- Cross-check the performance instruments to determine if the established attitude or power setting is providing the desired performance. The cross-check involves both seeing and interpreting. If a deviation is noted, determine the magnitude and direction of adjustment required to achieve the desired performance.

- Adjust the attitude and/or power setting on the control instruments as necessary.

Aircraft Control During Instrument Flight

Attitude Control

Pitch Control

Changing the “pitch attitude” of the miniature aircraft or fuselage dot by precise amounts in relation to the horizon makes pitch changes. These changes are measured in degrees, or fractions thereof, or bar widths depending upon the type of attitude reference. The amount of deviation from the desired performance determines the magnitude of the correction.

Bank Control

Bank changes are made by changing the “bank attitude” or bank pointers by precise amounts in relation to the bank scale. The bank scale is normally graduated at 0°, 10°, 20°, 30°, 60°, and 90° and is located at the top or bottom of the attitude reference. Bank angle use normally approximates the degrees to turn, not to exceed 30°.

Power Control

Proper power control results from the ability to smoothly establish or maintain desired airspeeds in coordination with attitude changes. Power changes are made by throttle adjustments and reference to the power indicators. Power indicators are not affected by such factors as turbulence, improper trim, or inadvertent control pressures. Therefore, in most aircraft little attention is required to ensure the power setting remains constant.

Experience in an aircraft teaches a pilot approximately how far to move the throttle to change the power a given amount. Power changes are made primarily by throttle movement, followed by an indicator cross-check to establish a more precise setting. The key is to avoid fixating on the indicators while setting the power. Knowledge of approximate power settings for various flight configurations helps the pilot avoid overcontrolling power.

Attitude Instrument Flying Using the Primary and Supporting Method

Another basic method for teaching attitude instrument flying classifies the instruments as they relate to control function, as well as aircraft performance. All maneuvers involve some degree of motion about the lateral (pitch), longitudinal (bank/roll), and vertical (yaw) axes. Attitude control is stressed in this site in terms of pitch control, bank control, power control, and trim control. Instruments are grouped as they relate to control function and aircraft performance as pitch control, bank control, power control, and trim.

Pitch Control

Pitch control is controlling the rotation of the aircraft about the lateral axis by movement of the elevators. After interpreting the pitch attitude from the proper flight instruments, exert control pressures to effect the desired pitch attitude with reference to the horizon. These instruments include the attitude indicator, altimeter, VSI, and airspeed indicator. [Figure 4] The attitude indicator displays a direct indication of the aircraft’s pitch attitude while the other pitch attitude control instruments indirectly indicate the pitch attitude of the aircraft.

|

| Figure 4. Pitch instruments |

Attitude Indicator

The pitch attitude control of an aircraft controls the angular relationship between the longitudinal axis of the aircraft and the actual horizon. The attitude indicator gives a direct and immediate indication of the pitch attitude of the aircraft. The aircraft controls are used to position the miniature aircraft in relation to the horizon bar or horizon line for any pitch attitude required. [Figure 5]

|

| Figure 5. Attitude indicator |

The miniature aircraft should be placed in the proper position in relation to the horizon bar or horizon line before takeoff. The aircraft operator’s manual explains this position. As soon as practicable in level flight and at desired cruise airspeed, the miniature aircraft should be moved to a position that aligns its wings in front of the horizon bar or horizon line. This adjustment can be made any time varying loads or other conditions indicate a need. Otherwise, the position of the miniature aircraft should not be changed for flight at other than cruise speed. This is to make sure that the attitude indicator displays a true picture of pitch attitude in all maneuvers.

When using the attitude indicator in applying pitch attitude corrections, control pressure should be extremely light. Movement of the horizon bar above or below the miniature aircraft of the attitude indicator in an airplane should not exceed one-half the bar width. [Figure 6] If further change is required, an additional correction of not more than one-half horizon bar wide normally counteracts any deviation from normal flight.

|

| Figure 6. Pitch correction using the attitude indicator |

Altimeter

If the aircraft is maintaining level flight, the altimeter needles maintain a constant indication of altitude. If the altimeter indicates a loss of altitude, the pitch attitude must be adjusted upward to stop the descent. If the altimeter indicates a gain in altitude, the pitch attitude must be adjusted downward to stop the climb. [Figure 7] The altimeter can also indicate the pitch attitude in a climb or descent by how rapidly the needles move. A minor adjustment in pitch attitude may be made to control the rate at which altitude is gained or lost. Pitch attitude is used only to correct small altitude changes caused by external forces, such as turbulence or up and down drafts.

|

| Figure 7. Pitch correction using the altimeter |

Vertical Speed Indicator (VSI)

In flight at a constant altitude, the VSI (sometimes referred to as vertical velocity indicator or rate-of-climb indicator) remains at zero. If the needle moves above zero, the pitch attitude must be adjusted downward to stop the climb and return to level flight. Prompt adjustments to the changes in the indications of the VSI can prevent any significant change in altitude. [Figure 8] Turbulent air causes the needle to fluctuate near zero. In such conditions, the average of the fluctuations should be considered as the correct reading. Reference to the altimeter helps in turbulent air because it is not as sensitive as the VSI.

|

| Figure 8. Vertical speed indicator |

Overcorrecting causes the aircraft to overshoot the desired altitude; however, corrections should not be so small that the return to altitude is unnecessarily prolonged. As a guide, the pitch attitude should produce a rate of change on the VSI about twice the size of the altitude deviation. For example, if the aircraft is 100 feet off the desired altitude, a 200 fpm rate of correction would be used.

During climbs or descents, the VSI is used to change the altitude at a desired rate. Pitch attitude and power adjustments are made to maintain the desired rate of climb or descent on the VSI.

When pressure is applied to the controls and the VSI shows an excess of 200 fpm from that desired, overcontrolling is indicated. For example, if attempting to regain lost altitude at the rate of 500 fpm, a reading of more than 700 fpm would indicate overcontrolling. Initial movement of the needle indicates the trend of vertical movement. The time for the VSI to reach its maximum point of deflection after a correction is called lag. The lag is proportional to speed and magnitude of pitch change. In an airplane, overcontrolling may be reduced by relaxing pressure on the controls, allowing the pitch attitude to neutralize. In some helicopters with servo-assisted controls, no control pressures are apparent. In this case, overcontrolling can be reduced by reference to the attitude indicator.

Airspeed Indicator

The airspeed indicator gives an indirect reading of the pitch attitude. With a constant power setting and a constant altitude, the aircraft is in level flight and airspeed remains constant. If the airspeed increases, the pitch attitude has lowered and should be raised. [Figure 9] If the airspeed decreases, the pitch attitude has moved higher and should be lowered. [Figure 10] A rapid change in airspeed indicates a large change in pitch; a slow change in airspeed indicates a small change in pitch. Although the airspeed indicator is used as a pitch instrument, it may be used in level flight for power control. Changes in pitch are reflected immediately by a change in airspeed. There is very little lag in the airspeed indicator.

|

| Figure 9. Pitch attitude has lowered |

|

| Figure 10. Pitch attitude has moved higher |

Pitch Attitude Instrument Cross-Check

- Overcontrolling;

- Improperly using power; and

- Failing to adequately cross-check the pitch attitude instruments and take corrective action when pitch attitude change is needed.

Bank Control

- Attitude indicator

- Heading indicator

- Magnetic compass

- Turn coordinator/turn-and-slip indicator

|

| Figure 11. Bank instruments |

Attitude Indicator

As previously discussed, the attitude indicator is the only instrument that portrays both instantly and directly the actual flight attitude and is the basic attitude reference.

Heading Indicator

The heading indicator supplies the pertinent bank and heading information and is considered a primary instrument for bank.

Magnetic Compass

The magnetic compass provides heading information and is considered a bank instrument when used with the heading indicator. Care should be exercised when using the magnetic compass as it is affected by acceleration, deceleration in flight caused by turbulence, climbing, descending, power changes, and airspeed adjustments. Additionally, the magnetic compass indication will lead and lag in its reading depending upon the direction of turn. As a result, acceptance of its indication should be considered with other instruments that indicate turn information. These include the already mentioned attitude and heading indicators, as well as the turn-and-slip indicator and turn coordinator.

Turn Coordinator/Turn-and-Slip Indicator

Both of these instruments provide turn information. [Figure 12] The turn coordinator provides both bank rate and then turn rate once stabilized. The turn-and-slip indicator provides only turn rate.

|

| Figure 12. Turn coordinator and turn-and-slip indicator |

Power Control

A power change to adjust airspeed may cause movement around some or all of the aircraft axes. The amount and direction of movement depends on how much or how rapidly the power is changed, whether single-engine or multiengine airplane or helicopter. The effect on pitch attitude and airspeed caused by power changes during level flight is illustrated in Figures 13 and 14. During or immediately after adjusting the power control(s), the power instruments should be cross-checked to see if the power adjustment is as desired. Whether or not the need for a power adjustment is indicated by another instrument(s), adjustment is made by cross-checking the power instruments. Aircraft are powered by a variety of powerplants, each powerplant having certain instruments that indicate the amount of power being applied to operate the aircraft. During instrument flight, these instruments must be used to make the required power adjustments.

|

| Figure 13. An increase in power—increasing airspeed accordingly in level flight |

|

| Figure 14. Pitch control and power adjustment required to bring aircraft to level flight |

As illustrated in Figure 15, power indicator instruments aircraft at a certain attitude. This allows more time to devote to the navigation instruments and additional flight deck duties. include:

- Airspeed indicator

- Engine instruments

|

| Figure 15. Power instruments |

Airspeed Indicator

The airspeed indicator provides an indication of power best observed initially in level flight where the aircraft is in balance and trim. If in level flight the airspeed is increasing, it can generally be assumed that the power has increased, necessitating the need to adjust power or re-trim the aircraft.

Engine Instruments

Engine instruments, such as the manifold pressure (MP) indicator, provide an indication of aircraft performance for a given setting under stable conditions. If the power conditions are changed, as reflected in the respective engine instrument readings, there is an affect upon the aircraft performance, either an increase or decrease of airspeed. When the propeller rotational speed (revolutions per minute (RPM) as viewed on a tachometer) is increased or decreased on fixed-pitch propellers, the performance of the aircraft reflects a gain or loss of airspeed as well.

Trim Control

Proper trim technique is essential for smooth and accurate instrument flying and utilizes instrumentation illustrated in Figure 16. The aircraft should be properly trimmed while executing a maneuver. The degree of flying skill, which ultimately develops, depends largely upon how well the aviator learns to keep the aircraft trimmed.

|

| Figure 16. Trim instruments |

Airplane Trim

An airplane is correctly trimmed when it is maintaining a desired attitude with all control pressures neutralized. By relieving all control pressures, it is much easier to maintain the aircraft at a certain attitude. This allows more time to devote to the navigation instruments and additional flight deck duties.

An aircraft is placed in trim by:

- Applying control pressure(s) to establish a desired attitude. Then, the trim is adjusted so that the aircraft maintains that attitude when flight controls are released. The aircraft is trimmed for coordinated flight by centering the ball of the turn-and-slip indicator.

- Moving the rudder trim in the direction where the ball is displaced from center. Aileron trim may then be adjusted to maintain a wings-level attitude.

- Using balanced power or thrust when possible to aid in maintaining coordinated flight. Changes in attitude, power, or configuration may require trim adjustments. Use of trim alone to establish a change in aircraft attitude usually results in erratic aircraft control. Smooth and precise attitude changes are best attained by a combination of control pressures and subsequent trim adjustments. The trim controls are aids to smooth aircraft control.

Helicopter Trim

A helicopter is placed in trim by continually cross-checking the instruments and performing the following:

- Using the cyclic-centering button. If the helicopter is so equipped, this relieves all possible cyclic pressures.

- Using the pedal adjustment to center the ball of the turn indicator. Pedal trim is required during all power changes and is used to relieve all control pressures held after a desired attitude has been attained.

An improperly trimmed helicopter requires constant control pressures, produces tension, distracts attention from crosschecking, and contributes to abrupt and erratic attitude control. The pressures felt on the controls should be only those applied while controlling the helicopter.

Adjust the pitch attitude, as airspeed changes, to maintain desired attitude for the maneuver being executed. The bank must be adjusted to maintain a desired rate of turn, and the pedals must be used to maintain coordinated flight. Trim must be adjusted as control pressures indicate a change is needed.

Example of Primary and Support Instruments

- Altimeter—supplies the most pertinent altitude information and is primary for pitch.

- Heading Indicator—supplies the most pertinent bank or heading information and is primary for bank.

- Airspeed Indicator—supplies the most pertinent information concerning performance in level flight in terms of power output and is primary for power.

Although the attitude indicator is the basic attitude reference, the concept of primary and supporting instruments does not devalue any particular flight instrument, when available, in establishing and maintaining pitch-and-bank attitudes. It is the only instrument that instantly and directly portrays the actual flight attitude. It should always be used, when available, in establishing and maintaining pitch-and-bank attitudes. The specific use of primary and supporting instruments during basic instrument maneuvers is presented in more detail in Airplane Basic Flight Maneuvers section.